Dissociative Identity Disorder, or DID, is not frequently encountered in therapy.

In the general population, DID occurs in 1 to 3% of individuals. Among psychiatric outpatients, it increases to 5-20%, in inpatient groups it is 15-30%, among child sex abuse survivors it is 50 to 80%.

Commonly first diagnosed at age 16 years of age, life circumstances play an important role in its emergence and maintenance.

I have personally treated two clients with a DID, ICD-10 (F44.81) diagnosis. One was in the 1990s when it was called MPD or Multiple Personality Disorder. I was an inpatient psychologist in Palo Alto, CA, at the time.

A few years back, an individual was referred to me from the University of Utah with puzzling behavior (referral question: “…individual seems like two people. Please advise.”).

Some psychologists specialize in treating DID. I’m not one, mainly because I haven’t worked with that many instances of DID, although I know a lot about it. Specialist practitioners likely view DID as trauma related (prominent in DID theories).

In its early years “multiple personality disorder” (DID) was linked to inborn personality disturbance. This is unlikely. Recent thinking has shifted from a “personality” designation toward “Dissociative Identity.”

The DSM-5 describes DID as:

A. Disruption of identity characterized by two or more distinct personality states, which may be described in some cultures as an experience of possession.

The disruption in identity involves marked discontinuity in sense of self and sense of agency, accompanied by related alterations in affect, behavior, consciousness, memory, perception, cognition, and/or sensory-motor functioning. These signs and symptoms may be observed by others or reported by the individual.

B. Recurrent gaps in the recall of everyday events, important personal information, and/or traumatic events that are inconsistent with ordinary forgetting.

C. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

D. The disturbance is NOT a normal part of a broadly accepted cultural or religious practice.

Note: In children, the symptoms are not better explained by imaginary playmates or other fantasy play.

E. The symptoms are NOT attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., blackouts or chaotic behavior during alcohol intoxication) or other medical condition (e.g., complex partial seizures).

Several DSM-5 criteria are noteworthy.

The presence of a main and an “alter” personality. The main personality is the original personality, and is generally intact. The “alters” are extensions of the “main” personality. The “alters” are not fully formed, even though some may be elaborate (with names, mannerisms, and semblances of a history). The personalities may or may not be aware of one another.

People are NOT born with DID. This set of behaviors/ideas/emotions emerged sometime in early adulthood. Most believe it is a response to a trauma that the individual perceives as threatening enough to fracture a coherent sense of self.

Memory gaps often go beyond ordinary forgetfulness (e.g., “I can’t recall what happened entirely on Tuesday, the day after I was…It’s like I wasn’t alive on that day…”).

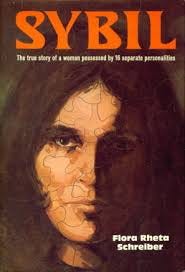

SYBIL

There are famous DID cases. The Three Faces of Eve (1957) is a book by Thigpen and Hervey (1956) about a DID case (made into a movie). Then, there is the case of “Sybil.”

Published in 1973 by Dr. Cornelia Wilbur, MD, a psychiatrist, it was an instant hit.

The story goes like this,

Shirley Ardell Mason was a client of Dr. Wilbur. Ms. Mason presented six distinct personalities during the course of therapy, reporting that these personalities began emerging in early childhood and continued to proliferate through Ms. Mason’s adolescent years.

Ms. Mason reported a highly dysfunctional family. She (and Dr. Wilbur) believed that trauma caused her to proliferate personalities to cope with ruthless abuse from her psychotic mother, Mattie Dorsett (who is pseudonymized in “Sybil” as “Hattie”).

When Ms. Mason was 4 y/o, Hattie tried to suffocate her by locking her into a box filled with grain. Hattie would hang Ms. Mason, then a preschooler, by the ankles above their kitchen table, rape her with household utensils, and force Ms. Mason to submit to ice-water enemas, then tie Ms. Mason under the piano. At the same time, Hattie would play crazed versions of Beethoven and Chopin while Ms. Mason was tied to the piano. These and many other horrific incidents perpetrated by Hattie on Ms. Mason occurred across years of unrelenting childhood abuse.

NOTE: The reports were not verified beyond Ms. Mason’s verbal descriptions.

Such ordeals continued, according to Ms. Mason, until Ms. Mason left home. Afterward, Ms. Mason tried to live an ordinary life. Still, the persistent emergence of personalities disrupted it. Some were under Ms. Mason’s control, others were not, with only fragmented memories of the many “alter” personalities and their behaviors as these occurred.

Dr. Wilbur, Ms. Mason’s therapist, meets Mason when Mason is a 22-year-old coed attending a Midwestern college of art. Mason complained of generalized “nervousness” to the extent that she was being asked to leave the college so she could be treated for her condition.

Dr. Wilbur, a psychiatrist, evaluated Ms. Mason, observing the unusual reports of her behavior, including significant gaps in her memory. Therapy started in January of 1946. Over time, Dr. Wilbur discovered the multiple personalities, most of whom were female, all with unique temperaments. As each personality emerged, this clued Dr. Wilbur to the kinds of issues Ms. Mason was experiencing at the time. Ms. Mason would shift in and out of different personality types at will and sometimes without awareness.

Mason reported no memory of the activities of the “alters” when the “main” personality was present, so Dr. Wilbur was unsure if the same (or a different) personality was engaged in the behavior of concern.

This transpired over a very long-term therapy relationship between Wilbur and Mason. The actual clinical story involves unusual therapies along the way. Dr. Wilbur frequently induced trances in M. Mason through drug (pentothal)- and hypnosis-induced interventions. These therapies were to pull repressed (or denied) trauma events from Ms. Mason.

Dr. Wilbur’s agenda included writing a book as an exposé to reveal to the public the horrific treatment of Ms. Mason and Ms. Mason’s compelling case of multiple personalities. NOTE: There are alternative versions of the “Sybil” story, some of which challenge this storyline.

The book was an instant hit, making Dr. Wilbur wealthy and well-known. A movie followed.

Client-therapist atypical activities continued. Ms. Mason followed Dr. Wilbur to NYC so treatment would continue. For a while, Ms. Mason began teaching art and was a NYC artist. Ms. Mason was never married. This was also the case for Dr. Wilbur, who some have speculated as desiring a daughter, which may have influenced the enmeshed relationship with Ms. Mason (https://www.cbc.ca/books/who-was-sybil-the-true-story-behind-her-multiple-personalities-1.4268459).

When Dr. Wilbur was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, Ms. Mason moved into Dr. Wilbur’s home to become Dr. Wilbur’s full-time caregiver until Dr. Wilbur died in 1992, leaving Ms. Mason $25,000 and all royalties from "Sybil" (the book). Ms. Mason lived for a few more years after Wilbur’s death, dying herself of breast cancer in 1998.

A strange story. The multiple quasi-personalities are reported to have emerged to a treating therapist. Ms. Mason, by her description, was a serial abuse victim by her own mother. Ms. Mason, traumatized, discovered an imaginal trauma-diminishing childhood coping strategy by proliferating separate personalities (my imaginary friend). Ms. Mason’s suggestibility during therapy and her attachment to Dr. Wilbur, in particular, are a troubling aspect of the case. Still, Ms. Mason’s tendency to become deeply attached to Dr. Wilbur also provides clues to features of Ms. Mason’s ongoing psychic needs that were likely never met, perhaps, until Ms. Mason met Dr. Wilbur.

Ms. Mason described an imaginal form of attachment to escape from the reality of her reported family-of-origin trauma. The publicity around this case raised public awareness. Whether helpful or not is unknown because in the late 1980s, it became fashionable to talk (or fake) multiple personalities for notoriety and attention. For example, more than 40,000 cases of MPD were documented that year, for a diagnosis which had been very rare (1 in 100,000 people) up to that point.

Such copycat behavior was likely driven by the popularity of the movie “Sybil.” Unfortunately, this distraction probably made it harder for the very few people with a bona fide MPD disorder to get credible treatment.

Dissociative Personality Disorder (DID) and Hysteria

Human psychopathology has always fascinated me.

This is probably because my mother was diagnosed with lifetime Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), in and out of psychiatric hospitals, psychotherapy, and psychiatric drug treatments, multiple suicide attempts, etc. She was a clever manipulator, a bright and attractive woman who felt she could read people’s minds and coerce them in ways she wanted.

Her life followed, in textbook fashion, the consequences of BPD.

As a child, raised by a mother with BPD, my early years were not easy. I have shared some details of my Mother’s story in an earlier entry. My sister is an emotional (and physical) mess to this day, in and out of psychiatric hospitals with a profound lifetime eating disorder, which she has managed in her later years by living with a second spouse in an isolated community in the Midwest, far from her home of origin. My father was a diagnosable, narcissist, and an alcoholic, blue-collar white trash oil-derrick worker. He was a stereotypical red-neck caricature of a human being.

They divorced when I was 16, and he died at 57 when I was 35 y/o from alcoholism (he was in an AA meeting when he fell over in the pews of a make-shift church, dead-on-arrival of a massive heart attack). His legs were so swollen near the end that he would split the shaft of his boots with a knife to get his feet into them. He gave nothing and left nothing to anyone, not even himself, dying like he lived as a lost soul by his own doing. When he died, I was a research scientist in Stockholm, Sweden. I didn’t give it much thought; he had been gone to me long ago.

This all happened a long time ago, but some memories remain. I’m not sure that my troubled early years guided my career in psychology, but my life story, if it has any meaning, will probably reflect this. I believe it will also reflect some learning from this period which probably explains why I was so interested in Mormonism at 16 y/o, a lost adolescent soul. There were reasons I was such a staunch True Believer until I was about 30 years old, when I opened my eyes and realized that I was heading down a path that made no sense to my rational mind.

I attribute some of my mind-expanding realizations to higher education, specifically after I left Brigham Young University and began my graduate work at Stanford University.

I was an oddball there until I adjusted and realized that the world was too complex to be fully explained by man-made religious ideologies.

Eventually, I also learned that higher education has good intentions, but is also a failing system in its own right, guided more by mean-spirited political realities, egos, and concerns for one’s own career among professors and leaders (both of which I was for a while until I left this as well) that undercut the learning of young minds who need to find support, meaning and purpose in life with some freedom to explore.

BPD is the imagination of one’s self gone horribly wild and outside of reality. It is trying to experience a dream of something that will never be and an inability to deal the harsh reality of self failure and disappointment as a consequence, but then blaming it on others to protect ones fragile sense of self. It is living who one is not, but unsure who one is. It is being lost in a profound way, surrounded by people, all of whom you feel like you need to discard, but at the same time are afraid to live without. This is my retrospective view of my mother while she lived and as I interacted with her. BPD, like DID, has at its core, is self-imagination and fantasy gone awry.

HYSTERIA

Hysteria has a much longer history as a psychiatric condition than DID.

Whether DID is an improvement on the original designation, I can’t say.

I’ve described the concept/label of HYSTERIA elsewhere in detail, so I refer the reader to the above entry. Contrasting hysteria (with an origin point of the 1880s) to DID (which appeared as Multiple Personality Disorder in about the 1930s) clarifies how psychiatric diagnoses and their labels evolve.

I repeat the definition of Hysteria:

You can compare this to the definition of DID at the beginning of this entry. If you study both, their meanings overlap. It might have been better to expand DID as a variant of Hysteria, diminishing some of the sensationalism around it.

THE POWER OF FANTASY

The underlying feature of these designations of emotional grandiosity in psychopathology is the word: IMAGINATION (or FANTASY). In a previous entry, I describe these words.

This is a genuine human capability. It comes from what we call “the mind” as distinguished from “the brain”. This has been a helpful duality, but also limiting, and it is presently losing its value in the contemporary world of technology, contemporary philosophy, and science.

Imaginative capability in humans likely arose as our brain structurally evolved to adapt to the demands of complex social groupings. In these, our human needs went beyond safety to the growth and perpetuation of our species, which, in part, involved thinking of ourselves as unique and with capabilities that we do not inherently possess.

The concept of God or Deity, for example, is an ideological leap that utilizes imagination to transcend harsh realities and human limitations that scare us, such as our mortality (e.g., we can live forever with a deity in an idyllic existence if we are good so to speak).

Human imagination can amplify and assuage fear, a primal and currently overemphasized aspect of our nature. For example, we fear negative evaluation, and this fear has been ingrained in our society to ensure conformity to social rules and norms. Concerning death, society not only accepts it but also counts on our mortality as one of the human features that allow for social renewal. It is a personal limitation, but a social requirement to ensure change, progress, and adaptation. Society has embraced the death of the single individual, regardless of how necessary that individual might seem to think he or she is to humanity. It has given people a salve of sorts in the form of religious/mystic ideologies.

Returning to my point, hysteria (or multiple personalities or DID) emerged, in part, from our imaginative capabilities extending beyond what is socially deemed as usual (or socially adaptive). DID is imagination out of control, so to speak. It is a person’s engaging this skill (imagination) for individual coping, but over time, it goes awry especially in the later years of changing social and or contextual forces of adult maturation pull for a greater focus on reality to live a “normal life.” (recall my earlier sentence: …Ms. Mason tried to live an ordinary life…the persistent emergence of personalities disrupted it…).

How does one control (or manage) one’s imaginative processes, at the individual level, when these become maladaptive?

This is the core question when dealing with these types of disorders. The question fits many psychiatric diagnoses: Paranoia, OCD, and the like.

There have been some attempts to reason through these psychiatric diagnoses using this question as a guide.

It is not realistic (nor helpful) to train people not to be imaginative. In fact, the opposite has more promise (note, for example: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy)

Most contemporary drug therapies dull brain function to the point that imaginative/emotional connections diminish making it hard to generate; that is, until the brain/mind can adjust itself to reality. It is then that drug treatment should be slowly titrated away (this is one problem of drug treatment that I describe elsewhere). This is why psychotherapy is useful and always will be valuable as an adjunct to this drug therapy.

Hypnosis can achieve a similar result, but it requires a higher degree of therapist skill and client cooperation and regularly timed sessions over a longer time interval to build a new paradigm of living to attain the same outcome. Hypnosis employs imagination to treat imagination-based disorders like hysteria and DID. This is how I treat Hysteria among clients I see and and it works well.

I’ve come to the end of this entry.

IN SUM

The takeaways are:

What underpins our human psyche, enabling us to learn, experience, connect, and find meaning, is imagination. We know what it means to generate aspects of our lives, not yet lived, through imagination and fantasy, but we struggle with learning how to employ imagination to help us cope with the realities of living.

As with any human capability, imaginative processes and the inherent power of the human mind to transcend reality can be learned to help you cope.

But, it does have a downside. We can imagine something fearful and then feel afraid. We can imagine failing, and subsequently, we do.

Imagination is closely tied to the core of our human psyche and our expectations. It is integral in our reasoning and conscious processes. Dreams and dreaming are a form of imagination that occurs as an autonomous process, whether we like it or not. We think of imagination as “free flowing,” and sometimes it is, but this is not always the case.

Can I harness the imaginative process to help me adapt to the world?

You probably already are.

So, the answer is an unequivocal YES.

However, there is a caveat: You may not think that you are in control of these processes (think of OCD in this regard), so unintended consequences can occur. The emergence of imaginatively based psychopathologies: DID, Obsessions, OCD, and the like, are examples of imaginative cycles that are out of individual control.

Using imagination as a coping tool is an entry I plan to write once the number of reads for this entry exceeds 100.

We are better off if we learn to live and manage some of the imaginative features of our psyche. Whether we want to call it our “unconscious” a word that our imagination has generated to give us a semblance of understanding ourselves, or whether we want to use drugs, therapy, religion, or new-age strategies all of which contain components of imagination as part of the approach, even drugs (e g. Ketamine therapy for depression).

Understanding (and using) our imaginative capability is worth considering in any psychological treatment for better mental health.