NOTE:

To keep this blog from becoming just a description of my personal philosophical viewpoints, I will balance out existential theme entries with those of a more practical purpose; that is, on adaptive functioning, exceptionalism, or psychopathology.

“Dr. What would you say is my diagnosis?”

Some clients are interested in their diagnosis. Why? It is something they recognize as self-descriptive.

If you are diagnosed with chronic depression, the symptoms you experience, including lethargy, a sense of hopelessness, helplessness, and worthlessness, are consistent with your phenomenology. Therefore, a diagnosis can clarify your emotional state. That’s why it’s one of the first tasks I undertake when I encounter a new client. Most clients don’t fit precisely into diagnostic boxes, some don’t fit at all, so diagnosis (or the absence of a diagnosis) is only a sketchy marker of mental health.

Diagnostic schemes are old. A 19th and 20th-century invention of the mental health sciences that has been refined over time. Diagnosis categorizes people whose behavior evinces worrisome or disruptive characteristics. Labels underpin how most mental health professionals think, through the lens of psychopathology.

Are you anxious, depressed, or paranoid? When you see a psychologist, you are usually not spending 50 minutes to improve your already excellent well-being. You often feel emotional pain, are uncomfortable, or disrupted. Most of all, you are looking for answers. Not just any answers, but specific answers that might point to some relief, and perhaps, a new life, a better way. You’ve tried to help yourself, to adjust your life, but it’s not working, so you seek professional assistance.

THE DIAGNOSTIC PROCESS

What is a diagnostic process? First, there is the observation that a person is behaving in unusual, strange, and disruptive ways (either towards themselves or towards others). Second, people behaving this way are asked why they are doing what they are doing, an assumption that something is internally not right with the person (think paranoia). If you are paranoid, you are highly suspicious and on edge, whether or not there is a legitimate reason for your suspicions. Third, is the detective work with the rudimentary tools that mainly stem from diagnostic schemes (psychological testing, MRI, microbiology, etc.) to discern what may (or may not) be physiologically wrong with you, What is causing such a disrupted internal world? By conjecture, What is producing the strange or disruptive feelings and behaviors?

This, of course, is an oversimplification of the diagnostic process, but diagnosis and its frameworks such as the DSM multi-axial system, have been the general approach that guides diagnostic tools that ultimately are used to label you as normal, abnormal, healthy, neurotic, psychotic, sane or insane.

There is, of course, substantial controversy about what diagnoses really mean, how they are used, whether they stereotype people, and if they are even helpful in guiding interventions to remediate mental health concerns. These questions are all valid.

As a professor, for 25 years, I taught classes in psychopathology, in diagnosis and the diagnostic interview, in learning the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder to the point of near memorization. Of the diagnostic labels that carry the greatest history, and still employed today, the term Hysteria is prominent. In this entry, I describe Hysteria; What it is, Where it came from, and Why it is important even if you don’t happen to be suffering from Hysteria.

HYSTERIA, WHAT IS IT?

The term, hysteria, as a precursory diagnostic label, has a long history in the psychiatric literature and as a diagnosable condition people still experience symptoms of hysteria. In fact, in some situations, a person could be diagnosed with hysteria even though the 21st Century term for it is different than in the past.

In the 21st Century, the idea of hysteria and its underpinnings still hold features of these historical roots, but the change in meaning and scope is considerable from, say, how hysteria was viewed in the 19th Century versus the 21st Century. The historical “Hysteria” label is an important topic for this entry because symptoms of hysteria run through many contemporary psychiatric diagnoses.

What is hysteria? What are symptoms of hysteria? Why do people develop hysterical conditions?

The dictionary defines “hysteria” as: exaggerated or uncontrollable emotion or excitement, especially among a group of people.

From Psychiatry, “hysteria” is defined as: a psychological disorder (not now regarded as a single definite condition) whose symptoms include conversion of psychological stress into physical symptoms (somatization), selective amnesia, shallow volatile emotions, and overdramatic or attention-seeking behavior.

The global history of the term, “hysteria” has been controversial. Before its classification as a mental disorder, hysteria was considered a female neurological ailment. Hysterical symptoms of “exaggerated or uncontrollable emotion or excitement… were described neurologically in 1880 by Jean-Martin Charcot.

There is an even earlier origin point for hysteria, going as far back as ancient Egypt, and to some extent, Greece. In antiquity, it was viewed as a singularly female disturbance in that it was believed that wombs of women capable of affecting the rest of the body’s health. Specifically, Hippocrates, believed that… (from The History of Hysteria, McGill University) “…a uterus could migrate around the female body, placing pressure on other organs and causing any number of ill effects. This “roaming uteri” theory, supported by works from the philosopher Plato and the physician Aeataeus, was called ‘hysterical suffocation’, and the offending uterus was usually coaxed back into place by placing good smells near the vagina, bad smells near the mouth, and sneezing…”

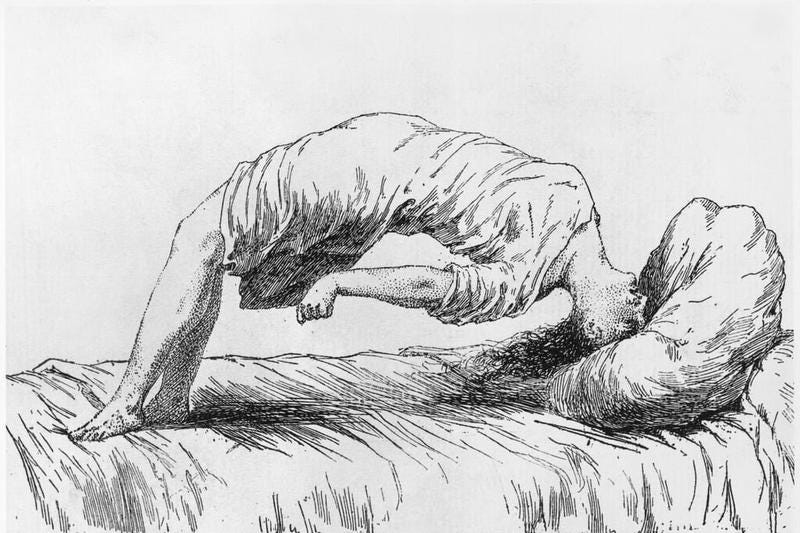

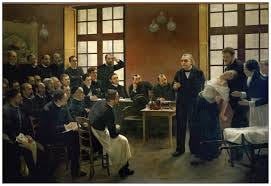

Jean-Martin Charcot, in 1880 France, in his lectures, would display photos and include live subjects in his demonstration lectures of hysteria (fainting, feigning physical illness). Charcot reasoned that symptoms were caused by an unknown internal injury affecting the female nervous system. It was Sigmund Freud along with Hans Beuer in Austria who extended Charcot’s theories further, writing several reports on female hysteria from 1880-1915. These reports described hysteria as primarily psychological. Freud believed that hysteria was due to a ‘psychological scar produced through trauma or repression’. Specifically, this damage was a result of removing male sexuality from females, an idea that stemmed from Freud’s ‘Oedipal moment of recognition’ in which a young female is unconsciously traumatized by the recognition that she has no penis, and the perceived sense that she has been castrated.

It was from this point in time that the term, Hysteria, became a basic medical and psychiatric explanation that men who dominated the medical and psychiatric professional specialties at the time found mysterious or unmanageable in women. This, then, stereotyped women as more vulnerable to psychopathology than, say, men. Fueling this gender stereotyping of the age such as the notion that women should be submissive, even-tempered, and sexually inhibited, the term proliferated and women suffered needlessly. Early treatments for hysteria involved regular (marital) sex, marriage or pregnancy and childbirth. These so-called treatments were all viewed from a medical point-of-view as “therapeutic” activities for women.

MODERN TRANSFORMATION OF HYSTERIA

The term “hysteria” with all its sordid history and stereotyping including substantial psychological damage, persisted in the medical and psychiatric literature until roughly the 1980s.

It was in in 1980, with the publication of the third edition of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the American Psychiatric Association finally officially changed the diagnosis of “hysterical neurosis, conversion type” into simply, “conversion disorder.”

So what is “conversion disorder”?

This requires a new look at some basic definitions.

The noun, conversion, is defined in the dictionary as: “the process of changing or causing something to change from one form to another.”

The Term Conversion Disorder is a psychiatric label that means: “a mental condition in which a person has blindness, paralysis, or other nervous system (neurologic) symptoms that cannot be explained by medical evaluation.”

What does “Conversion Disorder” look like?

To describe the features of conversion disorder it is essential, as I noted earlier, if one wants to stay within the “medical” model, to examine the specific symptoms of Conversion Disorder. These symptoms usually come on suddenly and look like a disruption of the nervous system (brain, spinal cord, or other nerves). Recall Charcot who mistook the symptoms of hysteria as caused entirely by a brain abnormality.

Movements that you can’t control

The experience of tunnel vision or blindness

Loss of smell or speech

Swallowing difficulties

Numbness or paralysis in some body part

Conversion Disorder diagnoses are made by default in that there are no tests to validly and reliably identify conversion disorder or verify its presence as a psychiatric condition. Therefore, the main task is “ruling out” any other possible physiological causes such as physical diseases (e g., epilepsy). Only then, and primarily by default, a person can be labelled as experiencing conversion disorder. In brief, the symptoms would need to have these characteristics:

They affect movement or the senses (cannot smell, hear, see), and the individual cannot control these manifestations.

The examiner or treating professional is fairly certain that the person is not faking it. In other words, it is not malingering (for example, blindness that is for the purpose of an insurance case).

Symptoms can’t be explained by any other condition, medication, or behavior.

Symptoms aren’t caused by another another mental health problem (e g. panic attacks).

The symptoms themselves cause maladaptive stress in social and work settings.

Prevalence of Conversion Disorder

Not surprisingly, the incidence of conversion symptoms varies depending on the group of persons being evaluated. Approximately 20 to 25 percent of patients in a general hospital setting have symptoms of conversion, and five percent of patients in this setting meet the criteria for the full conversion disorder diagnosis. Medically unexplained neurological symptoms account for approximately 30 percent of referred neurology outpatients and it from this subset of persons where conversion disorder is found. Out of 100 psychiatry outpatients, 24 will have unexplained neurological symptom, then, of these 24 maybe only two or three persons will have conversion disorder. Once again, women diagnosed with conversion disorder outnumber men by a 2:1 to 10:1 ratio

CASE STUDY OF CONVERSION DISORDER (SUSAN)

This Case Study of a patient diagnosed with conversion disorder, I’ve abstracted from a case I identified on the web. Although I have treated conversion disorder, and I could present a case from my own practice, this case is an excellent description of how enigmatic and elusive this disorder is to identify and then to treat.

A 20 year old female, Susan, received physical therapy for numbness and severe weakness on the left side of her body, specifically her leg. She complained of moderate low back pain. She noted that within the past year she was involved in a bicycle collision with a motor vehicle on her way home from school at a small community college. She reported that the vehicle clipped the front of her bike while crossing an intersection, causing her to crash hard on her left side. She has no memory if she hit her head, but she was wearing a helmet. She only recalls feeling very startled and dizzy after the collision with a couple of scrapes on her left leg. There are records that she was taken to a local hospital to screen for a concussion, which came back negative. Since the injury, Susan reports chronic dizziness that has now progressed to double vision. She has difficulty swallowing like there is a lump or obstruction in her throat, and notices she has started slurring words. She came in for treatment because she was have difficulty walking and has lost her balance since the accident and can no longer ride a bike. She reports having substantial stress and difficulty completing school work and this has gotten so severe that she has taken a leave of absence from school. Upon medical work-up there is no sign of blockage in her throat, and a neurological examination in areas that are not impaired seem intact.

Treatment

Treatment for conversion disorder is similar to treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Generally, there are steps to follow. I will highlight these below, but will not go into detail.

Develop a rapport with the client

Isolate if or where a trauma has occurred

Discuss trauma and its implications with the client

Acknowledge link to trauma and symptoms

Engage is a closer view of the trauma

Reframe the trauma (hypnosis can be helpful here)

Focus on positive aspects of functioning in the presence of the trauma

Deepen rapport with client

Help client build a world-view with values incompatible to trauma-restrictive values

Help client develop a world-view that incorporates that trauma as part of one’s life course.

In this case, it is highly likely that the client got the help she needed at the time of the accident, but the focus was on her safety and physical care. The idea that this trauma would have a psychological impact, even a trauma response, was probably overlooked. In fact, it might be that the client feels as if this was ignored, but unfortunately, what happened engaged a substantial trauma response. Perhaps, fear that her life was threatened, her own mortality might have been seen in the balance. She was possibly afraid to talk further about this because people would not understand her needs, so she emotionally buried the trauma and now its returning, only in another form that is once again threatening her (now, in a different way) and her wellbeing and future life course.