God and Mental Health (Part 1)

True Believer, Agnostic, Atheist: Does believing impact mental health?

I’m asked all the time. “Dr. I’ve lost my faith. Is God punishing me with depression (or anxiety)?” Or “I used to believe. I don’t anymore. “Is there a reason to live if there’s nothing after this?”

I’ve heard other things: “Dr. I was a true believer and depressed all the time until I left the Church. Then, all of a sudden I felt better.” “I was trapped in polygamy, but now I’m free and I don’t thank God for that.”

Living in Salt Lake City, I see many LDS (Latter-Day Saints) people who espouse an organized fundamentalist religious ideology, some are active, adhering to the doctrines of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons for short, although some don’t like this terminology). Some Mormons have lost faith, and feel like they are wandering in uncertainty. Others view their faith as essential to their own wellbeing and good mental health.

I see Christian and Catholic clients, some adherents to their faith, some “Cafeteria Catholics,” some Catholics by name only. I see Unitarian clients who struggle to believe what is ambiguous and different among their congregation.

Frequently, I’m asked of what faith I belong. I answer truthfully. I was born a “First Christian in Hanford, California” converted to Mormonism when I was 16 years old, departed on a two-year mission for the Mormon Church at age 19 years to New England, came home from this Mission, attended BYU, married, had two children, then (and that’s a big “then”) left activity in the Church for good and I haven’t been inside a Church in four decades. So, I have, for a time, been a True Believer, but this was in early adulthood. I know what it feels like to be an integral part of a religious ideology. For me, it was very good and very bad. When it was good, I felt at peace, watched over, secure. I was certain about the future whether I was following (or not) the tenants of the Church. So, as a true believer, my sense of life-ambiguity was low. When it was bad, I was angry, felt lost, wanted to escape, felt disconnected and misunderstood. My sense of life-ambiguity was high.

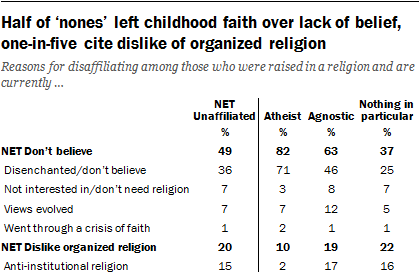

I digress from my personal story to present below the results of a PEW national survey of individuals who said they had been misclassified and were still affiliated with a religion. Among respondents, I would probably fall, on this questionnaire, as endorsing that my: “Views evolved, Religion causes conflict, Seeking/open-minded, Non-practicing” Where might you fall on this survey?

The Human Capacity for Religious Belief

I recall on my Mormon mission I was interviewed by the Mission President, a Mormon Missionary’s ecclesiastical leader. This was a regular monthly interview. I was six-months into my service. I recall that it was in Rutland, Vermont. The Mission President asked me, “Elder, Do you love the Lord?” I said “Yes” because at the time I was a True Believer. It felt good to say “Yes” because I was doing everything right. When I said, Yes, I knew at that time that even my thoughts were right because they were on missionary service. Then he asked me (Later, I presumed, this was a series of logical questions within the ideology) “Do you recognize me as your spiritual leader?” I said “Yes”. Then, The Mission President asked, Would you do anything for me? I said, “Yes”. Then, came what I call, the “kicker question” to separate the missionary wheat from the chaff. “Elder, if I asked you to run out in front of a car and kill yourself would you do it?” I was 19 years old, smart, especially in academics, completely committed. It was a Yes or No question, no room for hedging, like, ‘President, give me a chance to think about it.’ He wanted the answer right now. So, I said, “Yes” and when I did, I realized that it meant my life was over, and I felt great. I would run out in front of a car and I would be smiling all the way to my death. I started imagining myself doing it. But, fortunately, he didn’t ask me to kill myself, but a couple of days later he called me into the Mission Home in Cambridge, MA where I became his right-hand man. He was looking for loyalty, and he got it. I stayed in the Mission Home until my mission ended.

I’ve thought about this interchange many times since it occurred, and I’ve now lived a lot more years of life since then. I’m 65 years old, but still, this event is remarkable for me to recollect. I remember how good I felt when I said “Yes” to running out in front of a car and killing myself. Giving up your life for something larger than yourself, well, it’s a sublime, comfortable, strangely empowering feeling. All the ambiguity is gone.

This story tells me, as well, how the human psyche is wired. People can, indeed, lose themselves and their lives in serving God.

People can, indeed, strap a bomb around themselves and blow themselves (and others) up in the name of God and in one’s perceived service to God and be at peace the whole time they are doing it. People can be brainwashed to the point that they will leave anything and everything to join a cult that they truly believe in. This is even despite any reasonable evidence to the contrary.

It’s both a beautiful and an awful feature of human beings, this capacity to believe as I did. We are capable, to the point of individual obliteration, of serving what we personally decide is God. This story helps me understand a lot about what is happening around religion in the world today. It is also remarkable to believe this strongly and then lose it (as I ultimately did). Why do people fall away from something that they once truly believed in?

Religion is a powerful point of view. God is an exceedingly potent image to grab onto with hope. In Greek and Roman times, the Greeks played with Gods, powerful images who were also fallible. I think the Ancient Greeks created fallibility in their mythical Gods because they did not want to get caught losing all perspective in loyalty and obedience to an “all-knowing, all-seeing, all-powerful” image that one cannot or never will emulate or please. Unfortunately, for many people in the Western world, this is the disposition of our contemporary monotheistic God.

There are benefits in believing like this, but there are also substantial risks. Losing face with such a perfect spiritual image opens the door to self-hatred, self-punishment, and self-denial, which can make life miserable without recourse.

Now, I am agnostic by persuasion. I do, however, perceive what it means to believe in God and then depart from that belief. I can’t say that I am content; unfortunately, in agnosticism, one can never really be content because “not knowing” is not a reassuring point of view. Does God Exist? Maybe yes, Maybe no. So, my pilgrimage in this area is far from finished.

In this blog, I explore ideas about the Divine through different individuals who are living (or have lived) and espouse various viewpoints. Unfortunately, I have been unable to put the pieces together. I’m still living and trying, hoping to make discoveries along the way.

What Does the Mental Health Research Say about Religion and God?

Mental Health research about religion and God is expansive and diverse. It would fill volumes. Some research has become religion itself, a pro-access, pro-inclusivity religion, and a challenge to the privileged, whoever they are. There are disciplines in psychology devoted to religiosity, mental health, and inclusivity. For example, Division 36 of the American Psychological Association, Society for the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality applies “science” to religion. Division 36 is nonsectarian, it skirts endorsing if God exists. On the topic of “God,” it is silent. Their Mission Statement:

promotes the application of psychological research methods and interpretive frameworks to diverse forms of religion and spirituality; encourages the incorporation of the results of such work into clinical and other applied settings; and fosters constructive dialogue and interchange between psychological study and practice on the one hand and between religious perspectives and institutions on the other.

Nowhere in this statement can I find a reference to God. This explains why non-religious principles guide the psychological science of religion and spirituality. A goal of this learned society is not to take a stand on the existence of God but instead to view religion behaviorally. It does this by dividing religiosity into two groupings: 1) Internally-Driven Religion (or Spirituality) and 2) Externally-Driven Religion (or Church Attendance).

Someone, long ago, came up with this two-part distinction, and it caught on as a way to think about religion and mental health. When your Pastor or Bishop or Minister asks you to pray, this is internal-religiosity (spirituality). Faith is a form of spirituality, so it fits in the “internal” domain. “Treat People as You Would Want to be Treated - the Golden Rule” or “Join our Congregation.” These are examples of the “external” domain.

When it comes to Mental Health, Social Support is a gigantic asset that is connected to external religiosity. If you want to feel better, call a friend. This enlists social support. Attending a Church congregation every week, for some people, fosters a sense of belonging.

The Mormons are famous for their social support network including having their own Welfare program that my clients have accessed from time to time for instrumental assistance. This network can provide money, food, jobs and a list of resources for which the recipient pays for in volunteer work and, of course, allegiance to the Mormon Church. Leave the Church, and lose your Welfare benefits. Instrumental support can be a big plus for mental health, but in the case of Mormonism, there are always strings attached.

Knowing that you belong to a group that shares your values can be a source of moral support. Unless, of course, your values or the values of the group change and become incompatible.

Then, there is internal religion. Indeed, spirituality, however the individual defines it, can be a source of mental health benefits. There is much solace in meditation and prayer. This is whether or not an actual God (or grand external being) answers prayers. Prayer, like meditation, can clear the mind and open your thoughts to new ideas. Healing can occur through prayer, reflective contemplation, or sitting still and being at one with nature. Being in nature can generate a spiritual experience. A natural ambiance (trees, forest smells, the feeling of the wind in your face, being alone on an early morning in the woods) can be deeply inspiring - Think of Thoreau’s meditation in Walden Pond. This is where the power of healing is ostensibly present within the individual. Intrinsic religiosity is a label psychologists have given to the phenomenal state of spirituality.

But, Is there a God?

Who knows.

It seems no one does, although some have professed seeing or talking to God in person. Still, either way, no concrete evidence exists that God is a realistic being who watches over the world, especially God as a glorified human being, or even more ludicrous, God as a roughly 60-year-old White male with glowing white or silver hair and an untrimmed beard to match. But, then again, some religions espouse the notion that we are made in God’s image, so, once again, who knows?

In Mormonism, Joseph Smith, the founding prophet of this religious organization, claimed to have seen God in person. And Mr. Smith’s God was a man in a white robe who came along with Jesus Christ (also in a white robe, hair, and beard). Among other things, they told Mr. Smith not to join any Church. This then sets off the debate about what Joseph Smith, Jr. saw out there in the Vermont Woods.

Once again, Who knows? There were no corroborating witnesses to the event and no physical evidence it occurred. We only have the word of Joseph Smith, who assures the world that he stood in the physical presence of a deity.

But, whatever it was (or wasn’t) it was enough for Joseph Smith to usher in a world-wide religious organization that now consists of millions of “True Believers.”

The Pope of the Catholic Church speaks to God in prayer, but he has never declared seeing a God figure in person, nor does any modern-day Pope espouse this kind of experience. Catholicism prefers the “miracle” approach; that is, the appearance of a fantastic event that can then be connected to the existence of God. Certainly, there are written records like the Bible that describe God appearing in many forms and shapes (Moses seeing God in a burning bush), but again, this is a written historical record only. We are not entirely sure who the authors’ of this work are.

As an individual seeking mental health assistance from a living, existing, realistic being, “Our Father who art in Heaven…” remains, at best, unknown and more than likely unknowable except through the avenue of Faith. From the point of view of Mental Health Benefits, which is what this entry is about, believing in a realistic and extant God might be helpful, at least for some people, to catalyze a meditative or contemplative healing state.

Why?

Because, for some people, this ideology creates a point of clarification and focus. “People pray to God in Heaven.” In the end, God, or the God idea, can be a self-generated caring other, and for this reason alone, it probably has some mental health value. After all, who would benefit from praying to an unknown entity that exists outside of comprehensible space and time.

Belief in God on the Decline

I like this Gallup Poll slide because it tells an important story about God and Mental Health. 1) The findings indicate that more than half of the American population still believe God exists. 2) That believing in a literal God is in slight decline across the board. 3) The biggest drop is to the questions, “Convinced” that God exists. This has dropped from 79% to 64%. It seems here, that traditional, fundamentalist views of God are on the decline.

What does this say for mental health. In my view, it reflects the changing landscape of trust and confidence in our beliefs. As a people who may want to believe, we might be losing, slightly, some sense that there is an ultimate source to whom we can turn for extraordinary help. God, in general, is prescient (all knowing), all loving, unconditional in viewpoint.

This is different that the world at large which appears to be trending towards a more difficult, perhaps more hostile place to live, certainly more judgmental and untrusting. We are less able to look to someone or something to help us out of our difficult existence, and this bears on the concept of Hope. Hope may be declining along with trust, and when hope declines, mental health conditions, mental health vulnerabilities, fear, perceived uncertainty, loss of purpose proliferates.

Conversion: A Construct from Religion

Wouldn’t it be great to be born again? I mean, honestly, born again! Starting over, fresh, but still with some insight into what might have been a troubled past. Some might say “Yes,” and others say “No.” The answer hinges on what it means to be converted.

You hear this term all the time in fundamentalist religions. Johnny was a sinner; he was living an awful life, breaking the law and hurting himself and others. Then, Johnny found Jesus, and was “born again.” Presumably, being born again means Johnny was baptized (or inducted) into some brand of religious faith. Now Johnny is a new man. He now has permission to be happier, love people, and feel that life has a purpose.

So, what happened to Johnny. It appears from the story that Johnny was for a while living and feeling one way, then all of a sudden, he switched. Johnny became a new man so-to-speak, and the change appears to have happened almost overnight.

The concept of “conversion” intrigues me because it describes a kind of wholistic change that is both sudden and life-altering. For the truly, born again, it seems that life was going one way and then it switched. The person becomes psychologically new.

Exploring Conversion

If you take the term, “conversion” and look it up in the dictionary, it gives you the following definition:

…the act or process of changing something into a different state or form.

Psychologist have a term “Conversion Reaction” that underscores how conversion works in terms of psychopathology. I’ve actually worked with a client who had a conversion reaction, or an emotional conflict (anxiety) transformed into an apparent physical disability (limping). This was an wholistic change. The person was, for a time, one way, then, switched. No one (not even the person) knew how or why. So, the term, “Conversion Reaction,” makes sense.

…a mechanism by which emotional conflict is transformed into an apparent physical disability affecting the sensory or voluntary motor systems and having symbolic meaning

Conversion certainly has its place in religion. Even in the dictionary it appears as follows:

a converting or being converted ;

a change from lack of faith to religious belief; adoption of a religion

b. a change from one belief, religion, doctrine, opinion, etc. to another

If you think about conversion and religion, in Judeo Christian traditions, the story in the Bible of Jesus converting water into wine is a vivid depiction of conversion in action.

…On the third day a wedding took place at Cana in Galilee. Jesus’ mother was there, and Jesus and his disciples had also been invited to the wedding. When the wine was gone, Jesus’ mother said to him, “They have no more wine.”

“Woman, why do you involve me?” Jesus replied. “My hour has not yet come.”

His mother said to the servants, “Do whatever he tells you.” Nearby stood six stone water jars, the kind used by the Jews for ceremonial washing, each holding from twenty to thirty gallons. Jesus said to the servants, “Fill the jars with water;” so they filled them to the brim. Then he told them, “Now draw some out and take it to the master of the banquet.”

They did so, and the master of the banquet tasted the water that had been turned into wine. He did not realize where it had come from, though the servants who had drawn the water knew. Then he called the bridegroom aside and said, “Everyone brings out the choice wine first and then the cheaper wine after the guests have had too much to drink; but you have saved the best till now.” (John 2:1-11).

Why is conversion a useful concept? By itself, conversion probably doesn’t deserve much attention, but if you connect the idea of conversion to the continuum of change, it becomes clear that conversion is a very special kind of change. It is an wholistic change. Wine and Water are different in color (change). You could say that you like the color red more than looking at clear liquid, so changing clear to red - you could do this with food coloring. This would be, for water an asthetic (improvement), some might say that having the smell of wine at a wedding makes a difference in how the guests enjoy the wedding so this would be an (innovation) or something new. You have the added benefit of smell even when you don’t see the water (innovation). Then, if you pour it in clear glasses to transform the setting to be more festive. It is still a liquid, now water becomes an art form. You are using water in a transformative way. Making it art. But, in conversion the chemical composition of the liquid makes it not only a better looking (say red), a more pleasant smelling substance that pours into glasses, with additional internal physical properties including an alcoholic content (conversion).

To summarize: Positive Change can be delineated as: 1. improvement, then 2. innovation, then 3. transformation, and finally, 4. conversion.

These first three stages of change, improvement, innovation, transformation are used widely and without much thought, but they do seem along a continuum from insignificant to substantial. The word, “Conversion” rarely gets applied outside of religious contexts with the exception of some specialized areas like chemistry.

But, conversion means that something that starts out as one thing and ultimately ends up as totally another. Take one more example: A caterpillar goes through a number of stages of change. It finally comes out as a butterfly. This is the phenomenon of conversion.

At the end of this conversion, the butterfly looks entirely different, and its actions, motivation, purpose has been entirely converted. We don’t think of insects has having free will or high cognitive ability, but likely, the butterfly no longer thinks or acts like a larvae or feels like a larvae, it can fly and engage in a whole host of new activities for which its brain was wired while it was a larvae. These structures were existing while the larvae was a larvae, but they are now actualized into a butterfly. The insect no longer inches along, but it flies. This, I believe, is “conversion.”

Conversion and Mental Health

Many (if not most) clients I’ve seen tell me that they are on a life-long path in what I like call a slow conversion process. Notions of conversion, I believe, can sometimes be misunderstood - Conversion Occurs Instantaneously. The idea of being baptized and becoming a new person is one way to demonstrate instantaneous conversion. But this is a limiting view. It seems that conversion is embedded in the human psyche through the process of maturation.

Conversion and Maturation

Maturation, many believe, occurs primarily in our formative years. An infant matures on a fast-track of acquiring skills and abilities which then change the infant’s perceptions, beliefs, and behavioral proclivities. Infants learn to be cautious, but curiosity evolves, and infants seek attachment from others. This is the push and pull of maturation. Infants change rapidly, but some aspects of an infant do not change. These features of the psyche are “hard-wired.” Just like you, an infant is born with a specific kind a temperament and this temperament stays more or less the same throughout life. We’ve discussed this hardwiring phenomenon in an earlier entry. It has important implications for psychotherapy of adults.

Temperament,

Psychic Energy

Emotional Lability

Human beings change. They improve, they innovate, and they transform themselves over time. I like to think that they are engaged in a grand conversion process. Conversion involves change in our total, internal and external world.

The Case of Martha

Martha was a 34 year-old White female, unmarried, but with an infant girl. She lived in a predominantly Mormon household with two other sisters and a brother. Her parents were active Mormons and they raised the family as active Mormons. So, Martha attended Church from as early as she could remember up and to the point in time that she left Mormonism. At the time she saw me, Martha was struggling with her mood, was taking Fluoxetine, 80mg, for depression, along with Bupropion, 150mg at night. These were prescribed by her primary care doctor. She worked at a convenience store in the local area making minimum wage. She had, at present, no male relationships although she did have a former boyfriend, Kyle (same age as Martha), who was the father of her child, and with whom she was battling in Civil Court for child support unsuccessfully. Mary did manage to get a bachelor’s degree and a Master’s Degree in Massage Therapy. Unfortunately, she was deeply in debt for these degrees. She was living in her parents’ basement with no real hope on her part that she would ever leave.

She was an attractive young woman, I say this because her attractiveness in dress and presentation indicated that she cared about herself. She had a good family history and she reported that she had never been abused, and she had positive feelings towards her parents. She did note that her mother was neurotic in that the mother worried all the time.

But, Martha had severe boundary problems. For example, she wanted to sit next to me on the therapy couch because she said that this made her feel more comfortable. When I declined, she felt disappointed, but this issue allowed for an excellent entry into one of her largest problems, difficulty separating herself from others. She was almost innocent in her desire to become physically close to anyone with whom she started to develop a relationship. She couldn’t bear to see others suffer and would go to great lengths to help people even when it stressed her own personal resources.

When, Martha, at age 18, got entangled with a boyfriend who quickly became her sexual partner (her first sexual partner) and eventually the father of her child, Martha went through a whirlwind of changes. Kyle wanted to get out of Utah, she noted that he was an angry person, and the two of them moved, without parents’ good-will, to Montana where Kyle started working odd jobs and Martha tried to start a massage therapy business. By Martha’s report, Kyle fell into a rough crowd in Montana, started drinking and taking drugs. Martha did the same, but when she discovered she was pregnant Martha became worried about her baby and stopped alcohol and drugs. Kyle continued.

Kyle began lying to Martha, about illicit relationships, which she eventually discovered. It was then that Kyle became verbally abusive to her. They lived in a basement of an older run-down home in Montana. With no money or friends or family, they lived just on the edge of survival, and that’s when Martha’s mental health started breaking down. In one instance, she decided to kill herself by running away from home. She did so, on foot, living in and near dumpsters for about two-months until she became so malnourished she was found collapsed and near death by the police, after which she was placed in a psychiatric hospital with the diagnosis of schizophrenia. She remarked, “Dr. Hill, it’s amazing I’m still alive because I certainly wanted to die.”

Martha still wanted to die, but now, with a new baby boy she felt that she had a responsibility to stay alive and be a caregiver for her son. Kyle had left the picture at this point.

Her parents drove to Montana and brought her, and the baby boy, back home and she started living with them again. It was a very meagre existence. She couldn’t really work because she was caring for an infant. She had no friends, all of her old friends had moved on. Her siblings were distant. This is about the point that she started seeing me.

We began therapy focusing on her self-esteem because it was so low even when she could get out, she didn’t want to. Her weekly visits with me (these were constrained to weekly because this was all she could afford). Therapy went on for months, then a year, each week she kept returning, each week talking about herself, each week I slowly helped her shape her self-image in a realistic, but positive and empowering direction.

Slowly, but surely, her life started turning around. Her son started getting older, she got a job that was fairly satisfying, but then moved on to a better job, eventually starting her own business. She started exercising, eating better, taking care of herself. She discovered relationships with males and we worked through the ups and downs of this process. She never wanted to marry again, but she started to develop real feelings for another and she was able to set appropriate dating boundaries. This is not a flashy or glowing story, but it is a story of a full human conversion occurring over the space of years. I was always very careful to empower her. We even practiced things like setting boundaries. In the end, I would test her. I would ask her, say, if she wanted me to sit next to her on the couch and she learned to politely decline the breaking of a boundary and what it felt like to do so. I recall one thing she said to me.

“Dr. Hill, I really like your therapy style. You’ve sat there for about a year and I’ve come in and talked and talked and you’ve said very little, almost nothing. Then, after one year I’m a different person. How did you do that?”

This was an excellent observation because it opened the door to discussing her year-long conversion process. She was, truly, a different person. Some might say that she was an adult. A better way to describe it is that she saw the world one way, as a child, and then went through a gigantic series of experiences of which she was integrally involved, many of which she felt she had no control over, but over time she began to get control of her world and she began to shape it with some clear principles in mind. Principles like: Building independence, learning to develop and maintain meaningful relationships, setting boundaries around others and herself and learning what are her strengths and limitation, discovering a set of values through which she could develop her own moral compass.

I don’t see Martha any longer. It became apparent after several years, she had moved out of her parents basement into her own apartment, found a long-term boyfriend, started her own very successful business in Massage Therapy, established a set of parenting behaviors that were working for her and developing a world-view that was more empowering.

She no longer needed me, but she wanted me to stay around anyway. But, the day came for our last session, we reviewed her progress, she affirmed her progress in therapy, and off she went. In my view, she had experienced over a long time interval a kind of personal conversion. She was no longer the person that she was living in that basement in Montana.