Why?

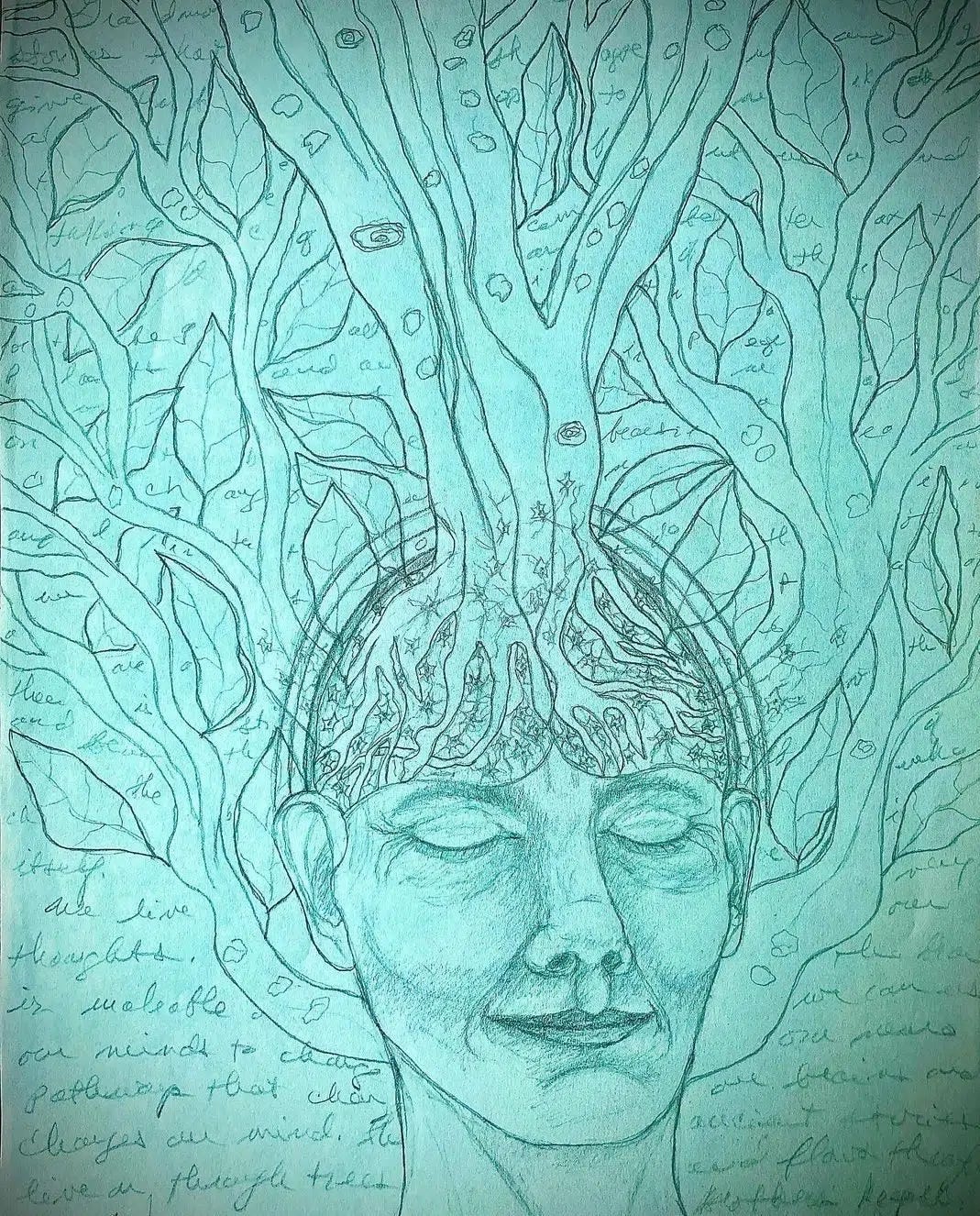

Because you live in your head.

All experiences originate within you:

Your mind only indirectly connects to others (like the branches of a tree).

Truism: No one can feel your feelings.

Most people are aware of this truism and value it when they want to be “left alone.”

Some say there are exceptions:

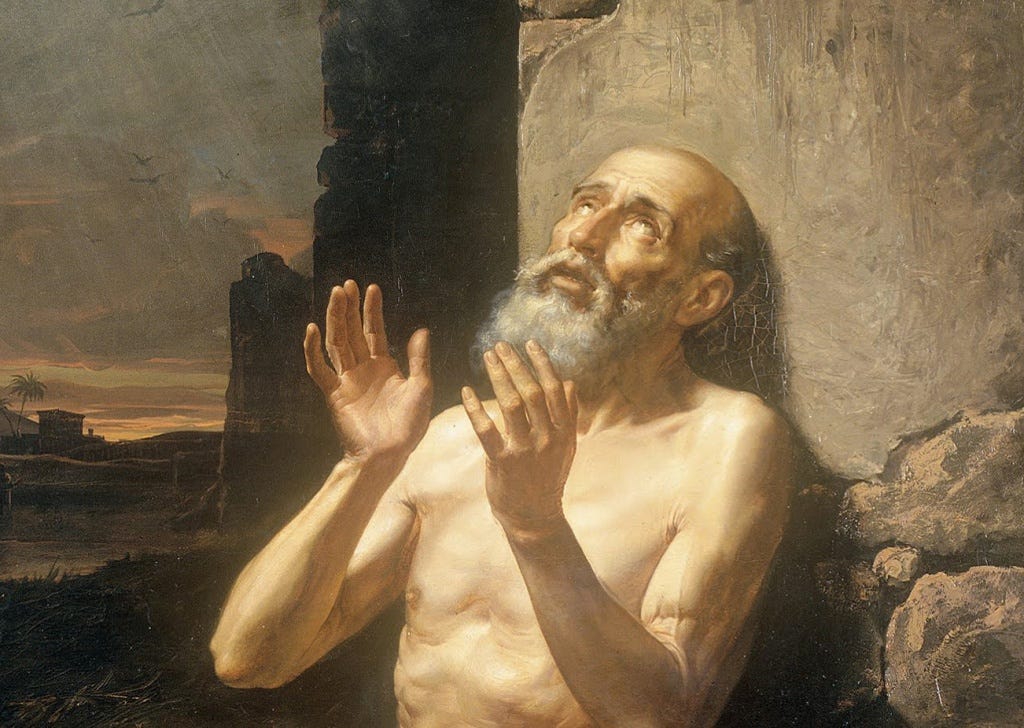

Your relationship with a “supernatural deity,” God, Allah, or Jesus, spiritual figures that, for some, offer solace from loneliness.

The Old Testament, specifically the Book of Psalms, is replete with admonitions that God knows and is with your innermost soul.

OT, Psalms 139:1-16, “…LORD, you have searched me and known me! You know when I sit down and when I rise up; you discern my thoughts from afar. You search out my path and my lying down and are acquainted with all my ways. Even before a word is on my tongue…” KJV.

The New Testament (NT) conveys this through a spiritual, ever-present companion intermediary, who, as NT writers declare, is with you continuously. Labeled “The Spirit of truth,” (Comforter) an internal being or state to whom you can appeal as needed.

NT, John 14:16-17, “…16 And I will pray the Father, and he shall give you another Comforter, that he may abide with you for ever; 17 Even the Spirit of truth; whom the world cannot receive, because it seeth him not, neither knoweth him: but ye know him; for he dwelleth with you, and shall be in you…KJV

But, is this really the case?

Some say YES, some say NO.

Others say you are not alone when you are with your spouse, partner, or soulmate.

But, is this actually the case?

Dr., do you understand what I’m feeling?

OR

Dr., can you sense my pain?

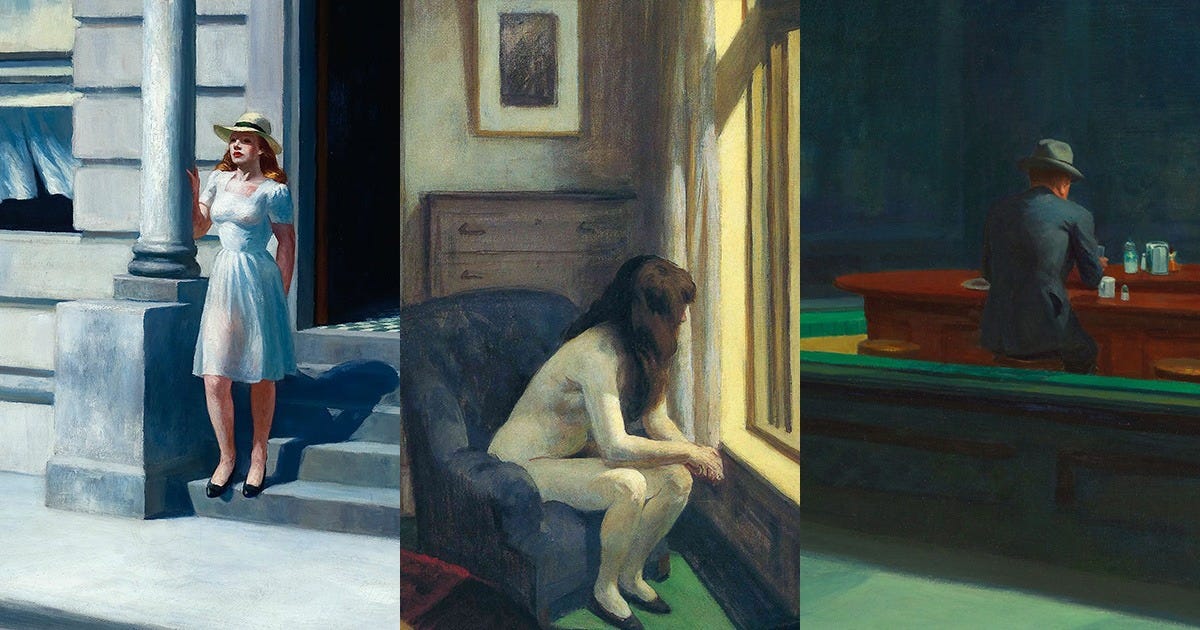

Psychotherapists (and their clients) are left disconnected when a client, in psychic pain, realizes that no one (except the client) can feel what the client is feeling.

Then, there is empathy.

Empathy is limited.

Empathy defined: Merriam Webster: 1: the action of understanding, being aware of, being sensitive to, and vicariously experiencing the feelings, thoughts, and experience of another...

The hedge in empathy is the word “vicarious,” which means that empathy only works “through imagination.” In empathy, we “imagine” someone’s pain.

There is a secondary definition of empathy that may mediate loneliness:

Empathy definition #2: …the act of imagining one's “own” ideas, feelings, or attitudes as fully inhabiting something observed (such as a work of art): The imaginative projection of a subjective state into an object (object = person) so that the object appears to be infused with it (the object alters one’s subjective state - as in a soulmate).

Still, the basis of either version of empathy is imagination.

You can only telegraph connection within yourself, and then, only through your imagination, can “you” feel (or sense) your most inner self connected to (or linking with) someone else. Whether the other person (object) feels this is unknown.

What about Compassion?

Compassion and Empathy are both caring responses to “someone else’s” distress.

Empathy refers to an active, imaginative sharing in the emotional experience of another person; compassion adds a desire (within the caregiver) to alleviate another person’s distress.

Regardless of how you construe it, fully sharing another’s inner feeling state, whether that state is loneliness, happiness, sadness, or a sense of belonging, is not humanly possible.

We are left to conjecture and subjectively connect through the medium of language and imagination (both verbal and non-verbal).

The Etymology of Loneliness

The word “loneliness” emerged in English in the 1500s to describe the condition of “being solitary.”

Between 1600 and 1800, the definition of loneliness evolved to reflect a feeling of “dejection for want of company,” such as in phrases like “lonely-hearted.”

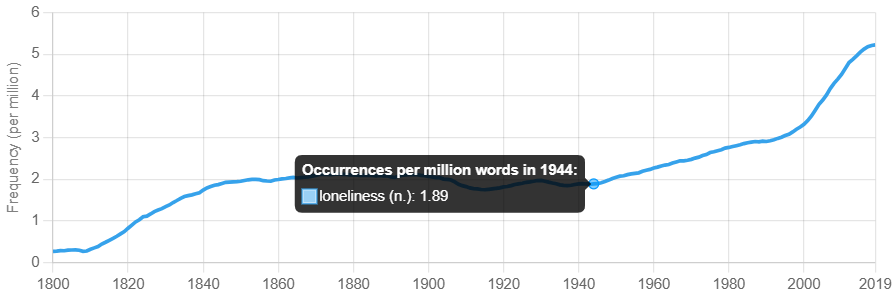

The frequency of use of the word “lonely” in the United States has increased over the years. Speculation as to “why” has focused on industrialization, technology, and the more diffuse nature of communication (e.g., smartphones).

21st Century definitions of “Loneliness” include: 1a: being without company, b: cut off from others; 2a: not frequented by human beings, 3a: sad from being alone…

The American Psychological Association Dictionary describes loneliness as: (n). affective and cognitive discomfort or uneasiness from being or perceiving oneself to be alone or otherwise solitary… Social psychology emphasizes the emotional distress…when inherent needs for intimacy and companionship are not met; cognitive psychology emphasizes the unpleasant and unsettling experience [of] perceived discrepancy…between an individual’s desired and actual social relationships. Psychologists from the existential or humanistic perspectives…[view]… loneliness as an inevitable, painful aspect of the human condition that …may contribute to increased self-awareness and renewal.

I’ve bolded the first sentence as the core idea of 21st Century “aloneness.”

Below is an opportunity to evaluate your state of “loneliness.”

UCLA Loneliness Scale:

Overview: The 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale is a self-report questionnaire designed to measure loneliness.

Response Format: The possible responses range from ‘not at all’ (1) to ‘often’ (4). The total score ranges from 20 to 80, with a higher score indicating greater loneliness.

Directions: Circle the stem (a to b) that best describes your answer.

1. How often do you feel that you are “in tune” with the people around you?

*a. not at all = 4, b. rarely = 3, c. sometimes = 2, d. often = 1

2. How often do you feel that you lack companionship?

a. not at all = 1, b. rarely = 2, c. sometimes = 3, d. often = 4

3. How often do you feel that there is no one you can turn to?

a. not at all = 1, b. rarely = 2, c. sometimes = 3, d. often = 4

4. How often do you feel alone?

a. not at all = 1, b. rarely = 2, c. sometimes = 3, d. often = 4

5. How often do you feel part of a group of friends?

*a. not at all = 4, b. rarely = 3, c. sometimes = 2, d. often = 1

6. How often do you feel that you have a lot in common with the people around you?

*a. not at all = 4, b. rarely = 3, c. sometimes = 2, d. often = 1

7. How often do you feel that you are no longer close to anyone?

a. not at all = 1, b. rarely = 2, c. sometimes = 3, d. often = 4

8. How often do you feel that your interests and ideas are not shared by those around you?

*a. not at all = 4, b. rarely = 3, c. sometimes = 2, d. often = 1

9. How often do you feel outgoing and friendly?

*a. not at all = 4, b. rarely = 3, c. sometimes = 2, d. often = 1

10. How often do you feel close to people?

*a. not at all = 4, b. rarely = 3, c. sometimes = 2, d. often = 1

11. How often do you feel left out?

a. not at all = 1, b. rarely = 2, c. sometimes = 3, d. often = 4

12. How often do you feel that your relationships with others are not meaningful?

a. not at all = 1, b. rarely = 2, c. sometimes = 3, d. often = 4

13. How often do you feel that no one really knows you well?

a. not at all = 1, b. rarely = 2, c. sometimes = 3, d. often = 4

14. How often do you feel isolated from others?

a. not at all = 1, b. rarely = 2, c. sometimes = 3, d. often = 4

15. How often do you feel that you can find companionship when you want it?

*a. not at all = 4, b. rarely = 3, c. sometimes = 2, d. often = 1

16. How often do you feel that there are people who really understand you?

*a. not at all = 4, b. rarely = 3, c. sometimes = 2, d. often = 1

17. How often do you feel shy?

a. not at all = 1, b. rarely = 2, c. sometimes = 3, d. often = 4

18. How often do you feel that people are around you but not with you?

a. not at all = 1, b. rarely = 2, c. sometimes = 3, d. often = 4

19. How often do you feel that there are people you can talk to?

*a. not at all = 4, b. rarely = 3, c. sometimes = 2, d. often = 1

20. How often do you feel that there are people you can turn to?

*a. not at all = 4, b. rarely = 3, c. sometimes = 2, d. often = 1

SCORING: SUM THE NUMBERS (NOTICE THAT SOME QUESTIONS WITH “*” ARE REVERSE SCORED). YOUR SCORE SHOULD BE BETWEEN 20 (NO SOCIAL LONELINESS) AND 80 (HIGH SOCIAL LONELINESS).

INTERPRETATION: THIS IS ONLY A MEASURE OF “SOCIAL LONELINESS.” FOR EXAMPLE, YOU COULD FEEL VERY SOCIALLY CONNECTED, BUT EXISTENTIALLY LONELY (SEPARATED FROM YOURSELF AND GOD, AS AN EXAMPLE).

SOCIAL LONELINESS IS A COMBINATION OF A FEELING STATE, SOCIAL SKILLS, AND A SENSE OF SOCIAL COMPETENCE.

RESEARCH:

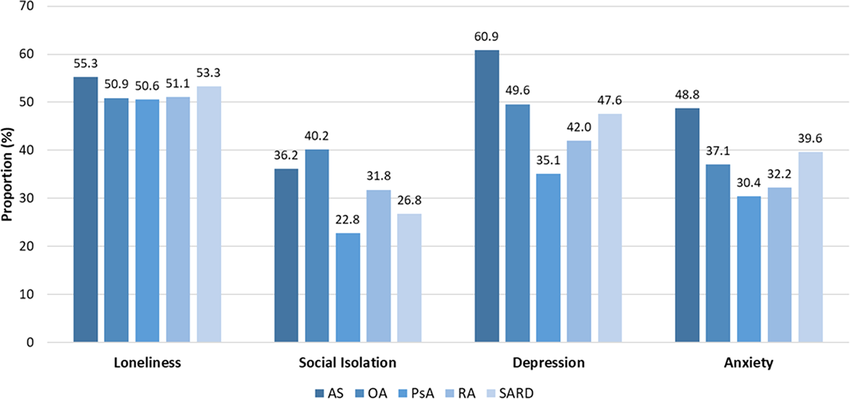

Sample: 718 people, mean age 45 years, mostly women with the following arthritis conditions (AS = ankylosing spondylitis, OA = osteoarthritis, PSA = psoriatic arthritis, RA = rheumatoid arthritis, SARD = systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease).

They were assessed with the UCLA loneliness scale.

Not only is loneliness high in this group, but all other psychological states are problematic as well (e.g., For Anxiety: A score greater than 10 is clinically significant).

LONELINESS AND AGING

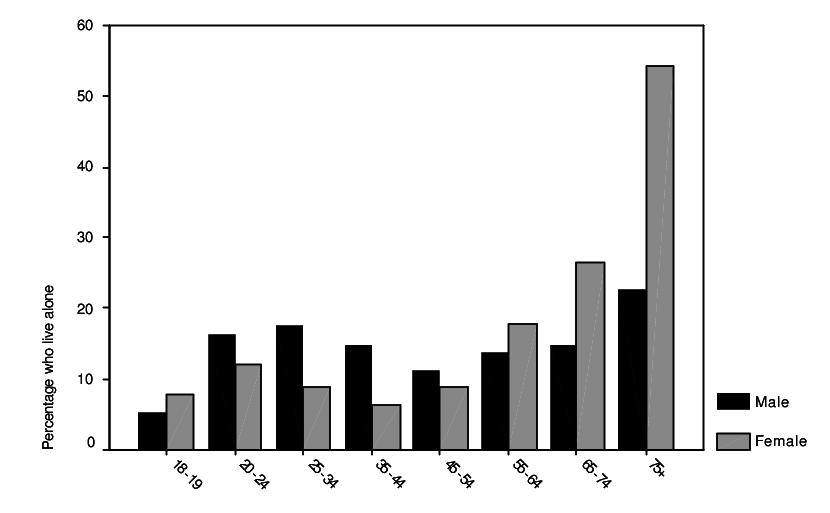

A sample of 13,000 Australians from the “Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey” was administered the UCLA loneliness scale.

The age range in this group was large.

This sample was from people “living alone” for various reasons. The data is similar to what might be collected in the USA.

Women in this study reported lower loneliness than men until later ages. Loneliness was substantial among women in the 56-64, 66-74, and 75+ year categories.

What does this survey reveal about aging and social isolation?

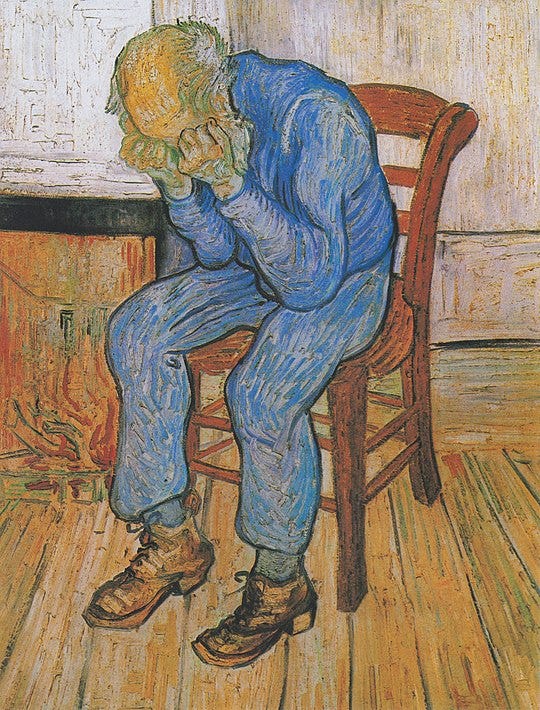

The “root” of loneliness is “absence.”

When a person feels “absence,” this means that the “essence” of something (or someone) formerly available to the person is now unavailable.

“Absence loneliness” describes grief, which is “loss.” Grief is the emotional consequence of an interpersonal loss.

A nonagenarian (90 years+) will experience recurring loss as the dying of loved ones accumulates. Aging in its advanced years is accumulating loss-related loneliness.

I saw Jim for 6 years, every week, as his psychotherapist.

When we first met, Jim was 84 years old. He came every week until he was 90 years of age, at which time he moved to an assisted care community. Jim said his cognitive issues had become so great that therapy was no longer meaningful to him. In the later years, our meeting times per session decreased, so towards the end, a session was only 20 minutes in duration.

Jim’s initial issue was grief due to the loss of a 50+ year spouse relationship. Their marriage had been average, according to Jim’s report. Over the last four years of their marriage, Jim was the sole caregiver for his spouse, which he came to resent.

He eventually placed her outside the home into 24-hour nursing care, and after 2 years in this setting, she died.

Jim never went to visit her in the nursing care unit. He learned about her death from the care facility's nursing staff. Jim was probably grieving her loss, but he never said so.

He did say he was angry with her because of the pain she had caused him from time to time throughout their marriage, and especially her difficult verbalizations towards him when her cognitive function began to fail.

He said, “Bob, when Marty died, I was the one who arranged her funeral - but I didn’t shed a tear. Why? I realized that anything I had in her was gone long ago, before she died. She had a few friends, and our children were there at the end with their children. Afterwards, I had no connection with these people, not even with my kids or their families. They were tied to Marty, not to me.”

I present this vignette because Jim is a typical client that I see, where loneliness predominates. Jim experienced what most might consider a significant life loss: the death of a 50+ year marital partner. Whether he liked her or not, she was with Jim for a very long time, another person to interact with during the long years of aging. For the final four years, and after Marty’s death, Jim was objectively and subjectively alone.

What kept Jim from falling into the deep trench of feeling alone, disconnected, purposeless, and without much life meaning? If you asked Jim, he would probably say something like this: “Bob, all I’ve got now are my routines.” I get up, fix myself breakfast, I exercise on and off, I watch some television, eat lunch, spend a little time reading the news, try to go to a coffeeshop or a local brewery for a few hours, I search the internet for topics that interest me, I like doing jigsaw puzzles and word games and this takes up some of my evening time. I go to bed, wake up the next morning, and do it all again.”

If you were Jim’s psychotherapist:

What suggestions might you have for Jim?

How might you live in your advanced age to stay interpersonally connected?

Where would you find meaning, especially in your 90s (if this is how long you happen to live)?

I could generate a “list” of things you could “do” to fill your days or find sources of meaning. Those reading would agree with me, but that’s as far as it would go.

Why?

Because such suggestions are “my” ideas, or maybe not even my ideas, but a list I’ve copied from another blog or webpage.

Instead, I will pose three questions that, if reflected on, might impact how you think about loneliness, being alone, experiencing disconnection from others, or feeling (grieving) the loss of someone important to you.

Why do I feel lonely right now?

What value (or meaning) does loneliness have in my life at this moment?

If I want to feel more connected, what could I do today or tomorrow that I’m not already doing?

Loneliness, like other challenging internal feelings, is of human origin. Loneliness is a personal “state of being,” not a “trait of character,” even though some people feel that being lonely is the only way they have ever felt. What this means is that we were not born lonely, but over time and through living, we encountered the experience of feeling an absence from others, others we care about. This eventually gets interpreted within the psyche as “loneliness.” We acquire loneliness in living. There is no such thing as a “loneliness” gene.

If one is always lonely, it may require some patience, reflection, and a shift in mindset to learn how to embrace being connected to oneself or others, especially if the person has learned to adapt to being disconnected.

Loneliness as a state of being is frequently a consequence of an unmet human need.

Although most people experience loneliness through the lens of “absence,” it can be framed as having a message specifically for you, not a message to ignore or to escape from, but a message to listen to.

What is loneliness’s message to you?