We’ve all lost someone. You can’t live on this planet without doing so.

Recently, My Mother. “Betty Yvonne Johnson (Hill) Badasci”

died. It was on August 27, 2024. She was 88 years old. Advanced age with COVID complications. I wasn’t present at her last breath.

She lived a long time, residing in a two-bedroom mobile-home trailer in Cayucos, California, an ultra-beautiful spot along the Central Pacific Coast 20 miles West of San Luis Obispo.

Cayucos has a population of 2,051. For the last quarter of a Century, she lived alone, and for the last 10 years, she rarely opened her windows or doors.

I know Cayucos well, having lived an hour and a half inland in the small rural town of Hanford, CA, population 10,000. We would vacation at the coast during my childhood and adolescence, staying in beach hotels and rentals. My sister and our cousins played along the beach, swam in the ocean, and rode bicycles up and down the Cayucos and Morro Bay Piers when we weren’t fishing off their edge or swimming at the beach.

I don’t remember seeing or connecting with my mother while we were there, but I knew she was around. She had to be, I reasoned, because she drove us and then disappeared.

My mother’s life included the failed marriage of my father, who died of alcoholism when he was 57 years old (They divorced when I was 16).

My mother met her second husband, Bill B., who, unlike my father, had wealth. He was a distant and challenging man whom I never knew beyond a handshake. He bought what we affectionately called my Mom’s trailer.” It resided in Whale Rock Terrace, a small luxury mobile home park on a hill overlooking the Pacific. The trailer was modest, but the views of the crashing Pacific coastline were spectacular.

This is where my mother settled, unlike “Bill,” who spent his final days in Hanford, CA, a dry and dusty farm community in the Central San Joaquin Valley where I was born. He died of Supranuclear Palsy, a terrible neurological disease, a consequence of his military service in the Korean War.

My mother had little concern for Bill. She married him for his money; she only wanted the trailer at the coast. She avoided him when he was gravely ill by staying in the trailer.

My mother’s life was fraught with deeply ingrained psychopathology; in and out of psychiatric hospitals, she was a master manipulator.

She was charming at times, mentally brilliant in subtle ways, and physically beautiful in her younger years. But her soul was crowded out with too many demons of selfishness and mental illness, along with hatred of herself and others.

My life with her, combined with an alcoholic father, was the pangs of psychopathology that worked on me as a child and young adult, creating intrapsychic turbulence throughout my life that required many years to repair. My sister was less successful and remains to this day a troubled soul.

No service, ceremony, or gathering followed my mother’s death. She was cremated with no plaque or physical marker. Her ashes went to my sister. I wrote her obituary. Short and sanitized, you’d never guess who she was or how she’d lived.

Unfortunately, my sister’s son, my mother’s executor, failed to publish it. So, like other unknown persons, my mother’s death certificate is the only marker of her existence.

My mother died like she lived, alone, unknown, disenfranchised, and anonymous to everyone, estranged from herself and from the natural beauty that surrounded her. She left no inheritance or even life mementoes. Born in near poverty, living with little she owned or cared about, and dying with nothing for anyone. In my case, perhaps only fragmented childhood memories - some good, most bad. Certainly, no motherly love as I construe it.

You might expect, given this gloomy backstory, that my feelings of grief for her would not be easy.

This is true.

I don’t bemoan my personal history. I eventually learned to live with it and by a simple mantra.

Bob Hill’s Mantra: “You Live with the cards you’re dealt.”

Defining Grief

Grief in the Oxford dictionary is 1…deep sorrow, especially caused by someone’s death…

The American Psychological Association Dictionary (2018) elaborates:

n. the anguish experienced after significant loss, usually the death of a beloved person. Grief is often distinguished from bereavement and mourning. Not all bereavements result in a strong grief response and not all grief is given public expression, such as “disenfranchised grief.”

Grief often includes physiological distress, separation anxiety, confusion, yearning, obsessive dwelling on the past, and apprehension about the future. Intense grief can become life-threatening through disruption of the immune system, self-neglect, and suicidal thoughts.

Grief may also take the form of regret for something lost, foremost for something done, or sorrow for a mishap to oneself.

American Psychological Association Dictionary (2018) continues:

Disenfranchised Grief:

…1.grief that society (or some element of it) limits, does not expect, or may not allow a person to express. Examples include the grief of parents for stillborn babies, of teachers for the death of students, and nurses for the death of patients. People who have lost an animal companion are often expected to keep their sorrow to themselves. Disenfranchised grief may isolate the bereaved individual from others and thus impede recovery. Also called “hidden grief.”

Complicated Grief:

…1 a response to death (or, sometimes, to other significant loss or trauma) that deviates significantly from normal expectations. Three different types of complicated grief are posited: chronic grief, which is intense, prolonged, or both; delayed grief; and absent grief.

The most often observed form of complicated grief is the pattern in which the immediate response to the loss is exceptionally devastating and in which the passage of time does not moderate the emotional pain or restore competent functioning. The concept of complicated grief was intended to replace the earlier terms “abnormal grief” and “pathological grief.”

Ambiguous Loss (grief)

A term coined in the ‘70s by the psychotherapist Pauline Boss. She described two types:

Type one ambiguous loss happens when someone is physically gone but psychologically there. This might refer to people who are missing or people whose bodies are gone in some way.

kidnapping

war

genocide

terrorism

natural disasters such as floods, hurricanes, and earthquakes

ethnic cleansing

Type two ambiguous loss happens when there is a lack of psychological presence while someone is physically there. This might refer to people who are emotionally or cognitively no longer available.

Losing a baby to miscarriage.

Having a parent with a substance use disorder.

Losing contact with a loved one via immigration.

Being a child of the foster care system.

Loss of dreams and plans due to setbacks or uncertainty.

Losing a loved one with a disease like Alzheimer’s or other memory-impaired illness.

Experiencing a loss without closure through a suicide or infant death (or separation - unavoidable or by choice).

In my Mother’s case, I would consider my grief, “ambiguous.”

I had emotionally disconnected from her years before her death. As a child, I could never understand why she could not love me. I couldn’t fathom a mother not caring about her biological offspring. But my mother was a complicated creature. Her verbalizations frequently did not match her actions. She sometimes told me she loved me, but I learned this was untrue. For a while, I thought she maliciously manipulated me: my feelings, my mind, even my soul. But, I let this go when I realized she couldn’t help herself or change her POV.

Eventually, I understood that she was driven by a deep-seated emotional illness, a tortured soul herself, probably with little choice in the matter. Although raised by good parents, my grandparents, who I was reasonably sure loved her (and me), I think even they were tacitly aware that something was wrong with my mother. This “something” was a phenomenon that they, I, or anyone else, could never fully understand.

This was a mental illness at its most apparent, and I learned to live with it for her sake and mine. My career path in clinical psychology may have been shaped by the effects of another’s mental illness on me.

“You Live with the cards you’re dealt.”

Treating Grief

If grief is complicated to define, treating it can be even more challenging. Some people come to grips with loss and ultimately embrace, positively, the memory of a loved one, now gone.

Others find solace in an ideology or belief system that perpetuates the hope that at some future point, perhaps in the eternities, there will be a grand reunion where children and parents, extended family of all sorts, will be made whole and then live together again in an idyllic unified environment.

This underscores the power and human capacity for imagination and fantasy. Human beings, in my humble opinion, have always yearned for something more or better, and sometimes, this becomes an idealization of the past (or a person from the past) who symbolizes perfection/beauty/positive recollection now lost. This is what can underlie the intensity and durability of a grief response.

Sometimes, as I’ve noted above, it can also be imagination for a sublime future worth striving for (Eternal Life). We frequently put conditions on these imagined states of existence, like the Calvinist connection between hard work and Heaven to motivate us in the present with a desirable goal.

In the end, it all boils down to what I call:

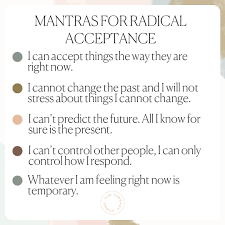

“Radical Acceptance”

This is a term popularized for all sorts of emotional and interpersonal maladies. It is also suited to grief and grieving. There is no other way to negotiate with grief without the power of personal acceptance.

Learning to Move On

Loss and grief emotionally underscore someone or something meaningful to an individual.

This meaningfulness is exquisitely apparent when the source of it (or at least what we think is the source of it) is no longer present or available to us in this finite state of living.

Taken to its ultimate level, I believe this is what gives all our lives such profound value, knowing (with certainty) that our life - as we experience it - will be taken from us through death just as it has taken every other human being before us.

Make no mistake: This is what it means to live life on earth. To experience life means that there is a beginning, a middle, and an end.

The beginning (birth) and end (death) are common. What happens in the middle greatly varies, including how much time in the “middle” we will be given/engage in/experience/use/value/throw away.

My POV is that the middle is mostly our time. Some people grieve that the “middle” has somehow been lost or taken away from them or that the middle, for them, never even existed. Some people are determined to remove the middle, hence the idea of suicide, which is when someone takes the middle out by force of Will.

In grief, the middle can seem to stand still as we observe and try to come to grips with the end state of another, particularly when the “other” is someone we care for, love, or cherish, but through death or other permanent means is now gone for good.

For some, time can stand still when we contemplate the challenge of continuing without the companionship of “our beloved other.”

Loss can traumatize people.

Why?

Because of our capacity to imagine, fantasize, and otherwise telegraph ourselves into other states of consciousness. We do this all the time, sometimes without even being aware. In grief, loss trauma can be challenging to manage. But, manage, we must do.

Grief is a highly individualized internal experience stimulated by an inevitable external event. (Loss).

Reconciling ourselves in grief to “loss” in all its forms and variations can also be a power to free oneself from the past, even in its capacity to generate personal sorrow and longing.

The press to negotiate with it as we move (or as the future moves) through us can be healing and empowering in many subtle ways. This, I believe, is at the heart of what I call “POSITIVE AGING.”

“You Live with the cards you’re dealt.”