Climate change is on everyone’s mind. I won’t discuss the evidence for or against global warming, but I presume most people would agree that the last few Summers have been some of the hottest in recent memory.

When ambient environmental temperatures rise and stay high, regardless of the cause, there are at least two kinds of human impacts. First, people start to feel, think, and behave differently. For example, high Summer heat has been linked to changes in group aggression as measured by frequency of violent crimes committed from burglary to murder. Population suicide rates seem to be positively correlated to higher sustained ambient temperatures. One study estimated a .7% increase in suicide rates in the United States and 2.1% increase in suicides rates in Mexico during periods of 1 degree Celsius increase over average monthly Summer temperatures.

I’m not saying high sustained ambient temperatures cause more group or self-violence, but I am saying there is at least a loose connection between the two. For example, high heat during the day pushes people to stay indoors and then they spend more time outdoors at night. More violence may be likely at night.

Second, heat impacts one’s own cognitive functioning. Studies examining this phenomenon follow people over time looking for changes in a person’s function from one’s own baseline.

Harvard researchers followed 44 healthy students and compared their: a. cognition, b. focus, c. processing, d. reaction times, and e. memory across a 12-day heat wave. Results showed students who lived in air conditioned dormitories had significantly better function in these domains than a matched group of students who lived in non–air-conditioned dorms. (see Guillermo-Cede J, Williams A, Oulhote Y, et al Reduced cognitive function during a heat wave among residents of non-conditioned buildings: an observational study of young adults in the summer of 2016. Plos Medicine. July 2018.

Heat is Pervasive

In the United States, this Summer, we find ourselves on a day-to-day basis confronted with the oppressive (and at times lethal) physical and emotional consequence of warming global temperatures. A recent essay in The Atlantic Daily, July 11, 2023, John Hendrickson, vividly underscores this point.

“In Austin, Texas, this week, a fire battalion chief measured a local playground slide at 130 degrees, practically hot enough to cause a second-degree burn within seconds. Last night in one part of the Florida Keys, the sea-surface temperature came close to 97 degrees. On Saturday, the Northwest Territories of Canada—up near the Arctic Ocean—hit 100 degrees. Last week was officially the hottest week ever recorded on Earth.

…consider the following: 54 million Americans could experience triple-digit weather this week. Phoenix, Arizona, may break its all-time record for consecutive days above 110 degrees. Death Valley could hit a whopping 130 on Sunday. None of this is a mere inconvenience. It can be lethal. The climate journalist Jeff Goodell, author of the new book The Heat Will Kill You First, described the experience of walking 10 blocks in Phoenix on a 115-degree day in a recent essay: “After walking three blocks, I felt dizzy. After seven blocks, my heart was pounding. After 10 blocks, I thought I was a goner.”

Is there a connection between hotter temperatures mental health?

I think most people would say, YES. Example: How do you feel during endless days of high heat above 95 degrees without a break, even when your air conditioning is running non-stop?

Mental health implications are mediated by human physiology, but the link between heat, physiology, and mind/brain effects is complex.

Why would temperature make Schizophrenia or Depression better or worse?

In one sense, more (or regularized) sunlight appears to benefit mental health conditions like SADD (Seasonal Affective Depressive Disorder - see my previous entry on this topic). So, sunlight is not all bad for mental health. But, what about ambient heat?

Are higher ambient temperatures (especially in the Summer) making your depression worse?

Knowing how heat (or in this case sustained high ambient temperatures) impacts the human physiology is important to review.

Heat and Human Physiology

Normal core body temperature is controlled between 97-99 F through blood flow wherein the body transports rising internal heat and releases it outside the body. This process, Thermoregulation, involves: 1. afferent sensing, 2, central control, and 3. efferent responses. To explain: Afferent sensing is body-wide receptors that determine core temperature. Central control = brain structures like the hypothalamus. Efferent response is sweating, vasodilation, vasoconstriction, shivering, etc.

Does thermoregulation stress impact mental health?

The answer seems to be an unambiguous, Yes. Consider extreme conditions that cause hypothermia, heat exhaustion or heat stroke. These are all caused when excessive heat breaks down thermoregulation. An interesting connection here is that when these conditions occur, when the body’s thermoregulation is overwhelmed, say, due to a heat wave, this disruption precipitates specific conditions, mostly related to neurotransmitter dysregulation of serotonin. Recall how important serotonin is in regulating emotional states.

In 2017, scientists discovered that the ambient temperature in Finland was correlated, nation-wide, with the amount of serotonin in the human system. This was particularly true in a group healthy volunteers the researchers identified and compared them to violent criminal offenders. As noted, serotonin is an important brain chemical that regulates anxiety, happiness and overall mood. Crucially, they also found a link between their measures of serotonin and the monthly violent crime rate. This study is far from definitive, but it does suggests that heat could alter our serotonin levels, which in turn could affect our level of experienced aggression.

Does thermoregulation stress impact sleep quality?

In an interesting PhD Thesis study, the PhD candidate (Lan L.) selected eighteen students (he was probably limited in funds because a bigger study would have been better) without sleep disorders. Lin created three temperature conditions in a sleep chamber. These were set at: 1. 23 °C, 2. 26 °C, and 3. 30 °C. A subjective questionnaire, physiological parameters, and a measurement of work efficiency evaluated sleep quality. After getting up on the next day, results indicated sleep quality at 26 °C was the highest. A higher or lower temperature was related to poor sleep quality. It seems high or low temperature activated the body’s thermoregulation system and this, in turn, diminished the subjects’ sleep quality.

See Lan L. Ph.D. Thesis. Shanghai Jiaotong University; Shanghai, China: 2012. Influence of Indoor Environment on Human Sleep Quality. (This PhD student should have published this study in a journal because it is well done.)

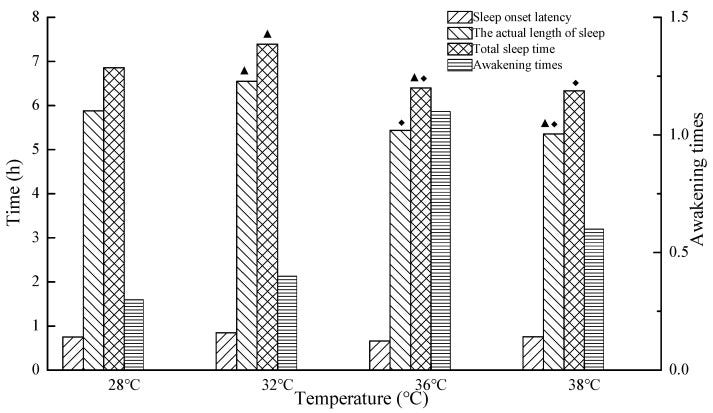

In a more ecologically valid study (although the sample size was still small, 10 college students (5 male and 5 female) slept in an apartment, and temperatures were the outside environment (probably Summer in Beijing). Subjects were monitored for 4 temperature centigrade intervals: a. 28, b. 32, c. 36, d. 38. Subjects slept and were monitored. They got several days off, then were monitored again. The sleeping patterns below are an amalgamations of sleep quality over time across four temperature intervals.

Actual sleep length was longest at 32 degrees, in fact most of the outcomes were optimal for 32 degrees.

This graph and Lin suggest an ideal temperature for sleeping. In this study it was 32 degrees C, or 89.6 degrees F. This is hot by our standards, but this was an inland Asian city and we are looking at relative, not absolute temperatures. The most important finding is that there is a more or less optimal sleep temperature, and this is probably related to thermoregulation, whether it is activated or not at the time of sleep.

Guozhong Zheng, Ke Li, and Yajing Wang. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019 Jan; 16(2): 270.The Effects of High-Temperature Weather on Human Sleep Quality and Appetite

Temperature plays an important role in the human sleep cycle.

As our bedtime nears, our core body temperature typically falls along with our heart rate, and this is thought to increase the familiar sensation of sleepiness. The veins in our hands and feet also open up to allow more blood to flow through them, increasing the temperature of our skin, decreasing core body temperatures, and increasing heat loss.

But on hot, sticky nights, it becomes harder for our bodies to lose this internal heat, which means we are unable to drift off to sleep. Hot night-time temperatures leads to more disrupted sleep leaving people feeling tired the next day. Being tired means being irritable, lacking motivation, and expressing a less than optimistic outlook. This is one more connection between high environmental temperatures and poor mental health.

Using a fan that can increase the airflow over your body at night. One researcher found that overhead ceiling fans help distribute air over the body and promote sleep, and that’s one reason people like them in the bedroom. Ceiling fans probably quiet thermoregulation.

Even opening windows (if there is no A/C present) can also help especially if there is a gentle breeze outside. Keep your curtains closed during the day, especially when the Sun is on the windows, This will help to prevent your bedroom from heating up.

Avoiding late night snacks can also help. Multiple studies have linked late night eating to elevated night-time core body temperatures. Energy is expended, though it's minimal, when one eats. A normal person may take 2-3 hours to digest all of his or her food. So, avoiding bed with a full stomach can promote sleep.

There is a new term in the mental health lingo: Climate Anxiety

Climate Anxiety

Climate Anxiety Defined is: Heightened emotional, mental or somatic distress in response to dangerous changes in the climate system. (From Climate Psychology Alliance. The Handbook of Climate Psychology. Climate Psychology Alliance, 2020).

Climate Anxiety is linked to various mental health symptoms including panic attacks, loss of appetite, irritability, weakness and sleeplessness. Climate Anxiety is prevalent (or at least reported frequently) among younger adults (ages 15-25), and by first responders to climate-related natural disasters, and by climate scientists and activists. These groups, for different reasons, are deeply engaged in information about climate threat.

One review examined the differential effect of Climate Anxiety to COVID19. COVID19 and Global Warming are environmental threats to our existence. COVID19 is more acute (and personal) than Global Warming. In COVID19 there is a tighter link between individual behavior and consequences of behavior. The Climate crisis is more diffuse with a focus on population effects. What to do about the Climate crisis is not clear, particularly for individual behavior. In both instances, climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic, there are substantial implications for disaster.

As with COVID19 and the Climate crisis there are huge opportunities for denial, anger and even despair. But, pin-point self-blame runs higher for COVID-19 than for the Climate Crisis. The Climate Crisis is a perfect real-life example of the “Boiling Frog Fable.”

“frog in the pot where the water temperature is being turned up ever so slightly until the frog is boiled to death but never really complains about it. Just gets more and more uncomfortable until the discomfort moves to intolerability and then death.”

The Climate Crisis and Hopelessness

Hope promotes health, hopelessness is toxic.

A growing number of people, if you asked about climate, will say the situation is hopeless. Climate Crisis doomsayers are everywhere. I list just a few climate doom & gloom sayings published on the internet.

There's little to nothing that we can do to actually reverse climate change.

We’ve already destroyed our planet.

There is no turning back from climate disaster.

It’s too late to fix global warming.

We are in an irreversible chain reaction beyond human control.

We are now watching the consequences of what we can no longer change.

How do these sayings impact you?

One is to dismantle any hope you might have that there is something you can do to impact world-wide climate issues. After all, you are just one person, and how can only one person impact an issue of this magnitude?

Doom Sayings tend to disempower, and that’s when defense mechanisms start to operate. To be disempowered is to be anxious, and to be anxious is to feel fear and threat. To deal with fear and threat that a person perceives cannot be controlled requires intrapsychic action. So, in comes denial, the frame of reference is shifted (climate crisis doesn’t exist) anxiety is gone. Pervasive denial in the presence of a real and progressive threat not only shuts down coping, but it damages mental health and any form of climate advocacy.

The group: “Mental Health Promotion Framework” that originates in Australia through The Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth) has developed a definition for “Mental Health”:

Mental health is not merely the absence of mental illness. Mental health is the embodiment of social, emotional and spiritual wellbeing. Mental health provides individuals with the vitality necessary for active living, to achieve goals and to interact with one another in ways that are respectful and just. (see (VicHealth): A Plan for Action 2005–2007: Promoting mental health and wellbeing. 2005, Melbourne: Victorian Health Promotion Foundation).

Hope is integral to this definition. To feel profoundly hopeless about anything would be a causative link to mental health vulnerability and illness.

How Can A Person Address Climate Anxiety and Hopelessness?

Cultivate optimism about the future.

Remind yourself there is a lot you can personally do.

Change your own behavior.

Become informed about problems and solutions.

Do things in easy stages.

Identify things that might get in the way of doing things differently.

Cue yourself.

Look after yourself!

Invite others to change.

Talk with others about environmental problems.

Present clear (but not overwhelming) information, and offer solutions.

Talk about changes that you are making in your own life.

Share your difficulties and rewards.

Be assertive, not aggressive.

Congratulate people for being environmentally concerned.

Model the behaviors that you want others do.

These are generic ideas that can mobilize a person to act in a purposive, meaningful, and values-driven way. Again, the issue is not how little or how much you can do, but rather: