The Transcendental (Part 2)

Underpinnings of the Psychology of Belief

I’ve encountered people who say they want to believe. This includes myself. I’ve also learned to appreciate the capacity to believe. To believe may be an innate human characteristic. The strong propensity to believe is mediated by our language (words, sentences, syntax, grammar) and our symbolic nature; that is, how we label objects with words.

When I say “tree” you immediately think of a physical tree. But labeling using words is, for the most part, arbitrary. In most languages, with few exceptions (Kanji), the word, “tree,” has no physical resemblance to a tree, but no matter, the word “tree” conjures in the mind the image of a “tree” to all people who speak and understand the English language.

The word “God” symbolizes the deity God. Depending on what they learn or discover about God, that deity can deviate somewhat in people’s minds. For some people, God is an old person with white hair who dresses in a white robe. God, for others, is an infinite cloud of energy with no discernible dimensions. The Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677) believed that God is the sum of the natural and physical laws of the universe, but not, in his view, an individual entity or creator personage. In his words, “By God I understand a being absolutely infinite, i.e., a substance consisting of an infinity of attributes, of which each one expresses an eternal and infinite essence.” For Spinoza, God is a substance.

The intensity of belief can range from the absolute skeptic who shuns belief in anything except what is directly observable or verifiable to the “True Believer” who myopically believes without respect to evidence, even to the point of giving up his or her free will for the object or the organization of the belief.

There is a quote, by the famous, but now deceased, Christian evangelist, Billy Graham, where he tries to describe what it means for him to believe:

“I have never been to the North Pole, and yet I believe there is a North Pole. How do I know? I know because somebody told me. I read about it in a history book, I saw a map in a geography book, and I believe the men who wrote those books. I accept it by faith. The Bible says, ‘Faith cometh by hearing, and hearing by the word of God’ [Romans 10:17 KJV].”

I think, at a superficial level Billy Graham is trying to express that, for him, the Bible was written by people who “knew” Jesus Christ and who "lived through” what happened. The writings of these people (now dead) are what Billy Graham believes is the Bible, and for him, the Bible is a true history of Jesus, the Son of God, because what was in the present (for those now dead people who wrote it) is now history for us, the living. Graham thinks (all people) should believe in the Bible or more precisely, the words of the Bible, just like we would believe the words and descriptions of someone who has traveled to the North Pole and then returns to write about it.

I note in this Billy Graham quote several additional features that may be indicative of “The True Believer,” of which he was. First, the connection between the perception of “belief,” and “knowing.” This association is tight (making “belief and knowing” almost indistinguishable). Second, to know something can be established if “somebody who “knows” tells me it’s true (I believe the men who wrote those books).” Here, “knowing” and reading about something is the same. The skeptic, in contrast, reads and evaluates everything without respect to “who” wrote it, not accepting at face value the written content no matter the source. Third, the word “I” (or the first person singular as it relates to third person plural “the men who wrote…”) is the strength of belief. For Billy Graham, it is his willingness to “accept” through “faith” what the Bible [book] says, “Faith cometh by hearing [or reading]…” “hearing the word of God…”

In other words, information that comes from a trusted source MUST be true; therefore, the Word of God (Bible) says God is real and, so, God must be real. In fact, for Billy Graham, God is so real that to read from the Bible makes God as factual as if God were standing right there in front of him. Because the Bible (trusted book…) says this is so, or as the famous children’s hymn says, “The Bible Tells Me So.”

Billy Graham, a Christian true believer anchors his belief in God through the Bible stronger, perhaps, than most people. After all, he was a preacher, and a preacher is usually a believer. His view epitomizes the “True Believer” because, once his pattern of belief was set in motion, it moved to faith, then to action, and then to certainty and then to knowledge. Belief and knowledge for Billy Graham, is one-in-the-same. For him, to believe is to know. He doesn’t need to understand (leave this to the scholars and skeptics), he need only believe. You must believe to preach and Billy Graham was a prolific preacher of the Word of God. He was not, in a technical sense, a seeker of truth, because he believes that he has already found the truth.

Why is believing so pervasive?

People can (and will) believe in almost anything, whether it be God, Allah, Heaven, Nirvana, Nature, Spiritual Enlightenment, Shaman, Spiritual Advisors, or even simply in Charismatic Others (think of the followers of the cult, “Heavens Gate” who followed their leader to their own deaths). Belief is powerful, partly because it simplifies things. It clarifies uncertainty. You don’t have to know everything to believe. In fact, to show any form of skepticism is, for the True Believer, to experience a disruptive presence. Disruption is always uncomfortable, so shunning skepticism makes sense for the “True Believer,” and by extension, believing makes life more purposeful, connected, meaningful and positive.

If we are all biologically wired to believe, becoming a follower of a belief system is more natural and easy than trudging through the world with the metrics of uncertainty and ambiguity. Not knowing how something works can frustrate the True Believer, but such frustration can be wiped away if belief is fully engaged. This is why it is easier, in some ways, to believe in things we cannot see or feel or hear or smell or explain in any evidentiary way. As I noted in Part 1, some call this this kind of belief “Faith” or “Complete trust or confidence in someone or something [to the point of action].”

Belief, in my view, is not faith, but is foundational to faith because belief does not pre-suppose action. Faith, on the other hand is to know and to know pre-supposes action. This is why faith, not belief, is the building block for hope. Faith created religion, religion did not create faith.

It is hope (a step beyond faith) that lifts the spirits, that causes a person to act, and that suggests a better future. Hope (not knowledge) is what the True Believer actually seeks. To move from belief, to faith, and then ultimately to hope is the goal of the True Believer.

A critical point here, at least to me, is the absence of belief, once you begin to probe into why a person has chosen not to believe, it is usually connected to some kind of fundamental disappointment. I also think “Trauma” can shatter the capacity to believe (I will describe this later), so, although people, in general, would like to believe, there are life circumstances and situations in life, perhaps in interactions with others, where the mechanism of belief breaks down and the ability to believe is nullified. When this happens, the true-believer becomes vulnerable to despondency, nihilism or other extreme forms of self-doubt where it seems that nothing in the world has real existence, meaning, or purpose.

Examples

“Dr., when I was a child I believed in all kinds of things. I trusted in things like God, Santa, the Fairy God Mother, my Guardian Angel. But then, this awful thing happened to me, I saw something that made no sense whatsoever, and I lost my ability to believe.”

or

“Dr. I was once a strong believer, but then I was disappointed by the Minister of my congregation, and now I no longer feel I can believe in anything.”

or

“I was a strong believer in God until I was deployed to Iraq. While there, I saw children murdered, bodies burning in the street, smelled the stench of senseless human death. I was sure that my life would be snuffed out any moment, and no one would care. When I came home, I couldn’t believe in anything, not God, not others, nothing…I saw malice and hatred everywhere. My soul was destroyed. It was like I died over there, only I’m not dead. I feel like a walking Zombie.”

I’m not arguing here that if a person is unable or unwilling to believe that this means somewhere in the person’s background, he or she has been harmed or disappointed, or that lurking in the person’s past is a trauma. My conjecture is only that there seems to be a connection between dis-belief and disappointment. It seems to me that the propensity to believe is almost a natural part of what it means to be a consciously sentient, optimistic, human being, and belief can be off-tracked by negative circumstances and life situations.

Jung and Belief

One of my favorites texts is a Memoir (of sorts) that Carl Jung wrote (he actually dictated it to an editor who then fashioned it into a book). The Memoir is entitled “Memories, Dreams, Reflections.” Jung published this memoir in the summer of 1956. The publisher, Kurt Wolff, helped Jung develop this text by asking Jung a series of probing questions about Jung’s life and work. Jung responded to these questions and embellished his responses. The subsequent text was transcribed and then formatted into an autobiography of Jung’s life, from childhood to adulthood.

It’s an enjoyable read, mostly, because his ideas are straight-forward and the text gives insight into the mind of a thinker of the transcendental who was also by training a psychiatrist, and a psychotherapist. Jung’s work with Freud, and, in particular, his many interactions with patients, his later life, etc. are all woven into this text. Jung’s interactions with his patients and then his subsequent musings about them in connection with his own life and experiences and travels are what I will focus on in this entry. I will quote liberally from this text.

When Jung was a boy, of perhaps 10 or 12 years old, he was living in his hometown of Basel (Switzerland). Jung’s father was the minister of the local church. His father was also a theologian and scholar of religiosity, formally constituted at that time.

QUOTE

…“I began looking in my father's relatively modest library---which in those days seemed impressive to me--for books that would tell me what was known about God. At first I found only the traditional conceptions, but not what I was seeking--a writer who thought independently.

At last I hit upon Biedermann's Christliche Dogmotik, published in 1869. Here, apparently, was a man who thought for himself, who worked out his own views. I learned from him that religion was "a spiritual act consisting in man's establishing his own relationship to God." I disagreed with that, for I understood religion as something that God did to me; it was an act on His part, to which I must simply yield, for He was the stronger. My "religion" recognized no human relationship to God [Recall here that Jung was 10 years old], for how could anyone relate to something so little known as God? I must know more about God in order to establish a relationship to him. In Biedermann's chapter on "The Nature of God" I found that God showed Himself to be a "personality to be conceived after the analogy of the human ego [here, the use of the human ego pre-dates by many years, Freud]: the unique, utterly supramundane ego who embraces the entire cosmos…

As far as I knew the Bible, this definition seemed to fit. God has a personality and is the ego of the universe, just as I myself am the ego of my psychic and physical being. But here I encountered a formidable obstacle. Personality, after all, surely signifies character. Now, character is one thing and not another; that is to say, it involves certain specific attributes. But if God is everything, how can He still possess a distinguishable character? On the other hand, if He does have a character, He can only be the ego of a subjective, limited world. Moreover, what kind of character or what kind of personality does He have? Everything depends on that, for unless one knows the answer one cannot establish a relationship to Him (God).

I felt the strongest resistances to imagining God by analogy with my own ego. That seemed to me boundlessly arrogant, if not downright blasphemous. My ego was, in any case, difficult enough for me to grasp. In the first place,…my ego was extremely limited, subject to all possible self deceptions and errors, moods, emotions, passions, and sins. It suffered far more defeats than triumphs, was childish, vain, self seeking, defiant, in need of love, covetous, unjust, sensitive, lazy, irresponsible, and so on. To my sorrow it lacked many of the virtues and talents I admired and envied in others. How could this be the analogy according to which we were to imagine the nature of God?

I either did not see or gravely doubted that God filled the natural world with His goodness. This, apparently, was another of those points which must not be reasoned about but must be believed. In fact, if God is the highest good, why is the world, His creation, so imperfect, so corrupt, so pitiable? "Obviously it has been infected and thrown into confusion by the devil," I thought. But the devil, too, was a creature of God. I had to read up on the devil. He seemed to be highly important after all. I again opened Biedermann's book on Christian dogmatics and looked for the answer to this burning question…What were the reasons for suffering, imperfection, and evil? I could find nothing.

That finished it for me. This weighty tome on dogmatics was nothing but fancy drivel; worse still, it was a fraud or a specimen of uncommon stupidity whose sole aim was to obscure the truth. I was disillusioned and even indignant, and once more seized with pity for my father, who had fallen victim to this mumbo-jumbo…”

Jung goes on to explore for himself the nature of God without much success, becoming more and more confused about the concept, until he ultimately rejects the Judeo Christian sense of “one God” or the Catholic sense of the Trinity “one-in-three-Gods.” But, he holds onto the God idea.

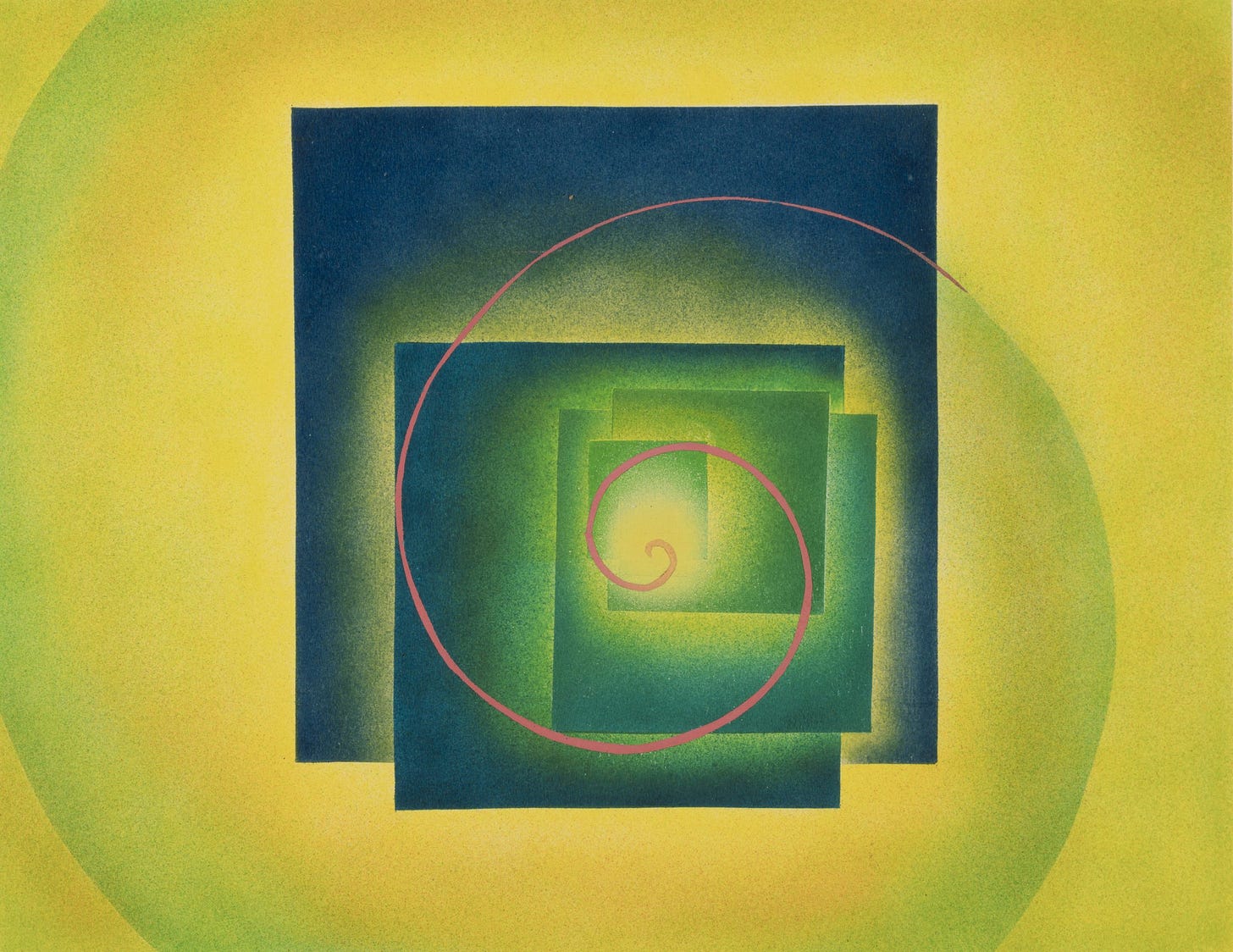

As I will discuss later, God, for Jung, eventually morphs into the Unconscious which, in Jung’s view, is a scientific reformulation of the God’s word. God, as a “person” is employed in myth and within the symbolism of myth and in this regard, the use of God fits because myth is required to transubstantiate what might be considered God (or the unconscious) formulated (or anthropomorphized) into the mortal body of a human being (as in the case of Jesus).

Is the Transcendental a Substitute for God

The answer to this question is an emphatic, NO.

I make this strong assertion because even though the word transcendental is much harder to grasp than the word “God,” the transcendental is actually easier to understand (and grasp) than the label “God.” The reason for this is that the “God” word has been so maligned over the history of humanity and has been used for so many unilateral and mixed purposes (even killing in the name of God) that the term “God” has been nullified as a useful label or descriptor.

For many, God immediately conjures up the image of an old Caucasian man with silver hair and a white robe which has really only had value for artistic works and easy appreciation or embodiment of the unconscious through myth. The dictionary defines God as:

Note: Two definitions are necessary here: A Christian Monotheistic God and an “other religions” God:

Monotheistic Definition: The creator and ruler of the universe and source of all moral authority.

Demi (other)-theistic Definition: a superhuman being or spirit worshiped as having power over nature or human fortunes.

If I say that I believe in God, then what do you imagine? That I am a: 1) Fundamentalist myopic nut who runs around thumping a Bible all day or 2) Catholic Priest in flowing robes who is in a constant state of ritualistic activity, or 3) Flowerchild of the the 1970’s who says that God is everything and the only important value in the world is love.

Plus, statements like, “Thou Shalt Have No Gods Before Me.” Is akin to idolatry or the worship of an idol God. “The Golden Cow.”

If I say I believe in God, then you will probably stop reading because you figure my mind is closed to the broader spectrum of ideas beyond the narrow views of Judeo Christianity.

I’ve had patients tell me that they “are” God. Why? Because, for one, it is an easy word to use in a sentence and for all kinds of things including infantile aggrandizement as is occasionally seen in the symptoms of schizophrenia. I’ve never, for example, heard anyone say, “I am the Transcendent.” Why? Because this word doesn’t conform to a God ideology.

Back to Jung (1956)

During his early years as a psychiatrist, Jung began to develop ideas and a point of view about what is and what is not valuable in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy in his case was a method, grown out of hypnosis, for guiding a patient to health or at least a belief in health. Jung had, here-to-fore, believed in theories and ideas, particularly related to repression and sexuality that were starting points for him to examine psychotherapy as a uniform method to help his clients back to a health. Eventually, Jung abandoned not only hypnosis, but these ancillary approaches as flawed points of view.

Here is one excerpt where Jung begins second-guessing the formal approaches of psychotherapy. Note: In this excerpt that Jung really doesn’t have an alternative direction to rely on:

QUOTE:

In many cases in psychiatry, the patient who comes to us has a story that is not told, and which as a rule no one knows of. To my mind, therapy only really begins after the investigation of that wholly personal story. It is the patient's secret, the rock against which he is shattered. If I know his secret story, I have a key to the treatment. The doctor's task is to find out how to gain that knowledge. In most cases exploration of the conscious material is insufficient. Sometimes an association test can open the way; so can the interpretation of dreams, or long and patient human contact with the individual. In therapy the problem is always the whole person, never the symptom alone. We must ask questions which challenge the whole personality.

Here, Jung was moving towards a deeper understanding of what it meant to be a person. Treating an individual patient, Jung surmised, requires knowing the person and appreciating the person as a unitary whole. A person is both idiosyncratic and universal (e g. the person’s secret story is usually based on a universal myth). It was at this point that Jung began to look for something he could understand that was larger than himself, but was not constrained by a static image (such as God), or static ideas found in what “Science” at the time was preaching about the human psyche. He began here to discover that mythology was an important subject matter for treating the individual person:

QUOTE

…Since the essence of psychotherapy is not the application of a method, psychiatric study alone does not suffice. I myself had to work for a very long time before I possessed the equipment for psychotherapy. As early as 1909, I realized that I could not treat latent psychoses if I did not understand their symbolism. It was then that I began to study mythology. With cultivated and intelligent patients the psychiatrist needs more than merely professional knowledge. He must understand, aside from all theoretical assumptions, what really motivates the patient. Otherwise he stirs up unnecessary resistances. What counts, after all, is not whether a theory is corroborated, but whether the patient grasps himself as an individual. This, however, is not possible without reference to the collective views, concerning which the doctor ought to be informed. For that, mere medical training does not suffice, for the horizon of the human psyche embraces infinitely more than the limited purview of the doctor's consulting room [Here, Jung is beginning his journey into the transcendent]. The psyche is distinctly more complicated and inaccessible than the body. It is, so to speak, the half of the world which comes into existence only when we become conscious of it. For that reason the psyche is not only a personal but a world problem, and the psychiatrist has to deal with an entire world. Nowadays we can see as never before that the peril which threatens all of us comes not from nature, but from man, from the psyches of the individual and the mass. The psychic aberration of man is the danger. Everything depends upon whether or not our psyche functions properly. If certain persons lose their heads nowadays, a hydrogen bomb will go off. The psychotherapist, however, must understand not only the patient; it is equally important that he should understand himself. For that reason the sine quo non is the analysis of the analyst, what is called the training analysis. The patient's treatment begins with the doctor, so to speak. Only if the doctor knows how to cope with himself and his own problems will he be able to teach the patient to do the same. Only then. In the training analysis the doctor must learn to know his own psyche; and to take it seriously. If he cannot do that, the patient will not learn either. He will lose a portion of his psyche, just as the doctor has lost that portion of his psyche which he has not learned to understand. It is not enough, therefore, for the training analysis to consist in acquiring a system of concepts. The analysand [patient] must realize that it concerns himself, that the training analysis is a bit of real life and is not a method which can be learned by rote…There are many cases which the doctor cannot cure without committing himself. When important matters are at stake, it makes all the difference whether the doctor sees himself as a part of the drama, or cloaks himself in his authority. In the great crises of life, in the supreme moments when to be or not to be is the question, little tricks of suggestion do not help. Then the doctor's whole being is challenged. The therapist must at all times keep watch over himself, over the way he is reacting to his patient. For we do not react only with our consciousness. Also we must always be asking ourselves: How is our unconscious experiencing this situation? We must therefore observe our dreams, pay the closest attention and study ourselves just as carefully as we do the patient. Otherwise the entire treatment may go off the rails. I shall give a single example of this.

I once had a patient, a highly intelligent woman, who for various reasons aroused my doubts. At first the analysis went very well, but after a while I began to feel that I was no longer getting at the correct interpretation of her dreams, and I thought I also noticed an increasing shallowness in our dialogue. I therefore decided to talk with my patient about this, since it had of course not escaped her that something was going wrong. The night before I was to speak with her, I had the following dream.

I was walking down a highway through a valley in late-afternoon sunlight. To my right was a steep hill. At its top stood a castle, and on the highest tower there was a woman sitting on a kind of balustrade. In order to see her properly, I had to bend my head far back. I awoke with a crick in the back of my neck. Even in the dream I had recognized the woman as my patient. The interpretation was immediately apparent to me. If in the dream I had to look up at the patient in this fashion, in reality I had probably been looking down on her. Dreams are, after all, compensations for the conscious attitude. I told her of the dream and my interpretation. This produced an immediate change in the situation, and the treatment once more began to move forward. As a doctor I constantly have to ask myself what kind of message the patient is bringing me. What does he mean to me? If he means nothing, I have no point of attack. The doctor is effective only when he himself is affected. "Only the wounded physician heals." But when the doctor wears his personality like a coat of armor, he has no effect. I take my patients seriously. Perhaps I am confronted with a problem just as much as they. It often happens that the patient is exactly the right plaster for the doctor's sore spot. Because this is so, diffcult situations can arise for the doctor too--or rather, especially for the doctor.

The majority of my patients consisted not of believers but those who had lost their faith. The ones who came to me were the lost sheep. Even in this day and age the believer has the opportunity, in his church, to live the "symbolic life." We need only think of the experience of the Mass, of baptism, of imitatio Christi, and many other aspects of religion. But to live and experience symbols presupposes a vital participation on part of the believer, and only too often this is lacking in people today. In the neurotic it is practically always lacking. In such cases we have to observe whether the unconscious will not spontaneously bring up symbols to replace what is lacking. But the question remains of whether a person who has symbolic dreams or visions will also be able to understand their meaning and take the consequences upon himself.

This last paragraph is important because it is at this point that Jung begins to explore the relationship between universal symbols (as in mythology) and the individual struggling with the challenges of life. His idea is that people never struggle with simply personal issues, there is always something larger. This is, in my view, the notion of the TRANSCENDENT. I will explain more about this as we progress in this entry.

The Chapters in this Memoir then move to Jung’s encounters with Freud as well as his world travels, especially his travels to Sub-Saharan Africa, India, and Egypt. He reports the following experience with Freud. This series of encounters is why ultimately Jung felt he could never be a follower of Freud or Freud’s ideology:

FREUD

I first took up the cudgels for Freud at a congress in Munich where a lecturer discussed obsessional neuroses but studiously forbore to mention the name of Freud. In 1906, in connection with this incident, I wrote a paper…on Freud's theory of the neuroses, which l had contributed a great deal to the understanding of obsessional neuroses. In response to this article, two German professors wrote to me, warning that if I remained on Freud's side and continued to defend him, I would be endangering my academic career. I replied: "If what Freud says is the truth, I am with him. I don't give a damn for a career if it has to be based on the premise of restricting research and concealing the truth." And I went on defending Freud and his ideas. But on the basis of my own findings I was still unable to feel that all neuroses were caused by sexual repression or sexual traumata…

…as I came to know Freud… I could see that his sexual theory was enormously important to him, both personally and philosophically.

Above all, Freud's attitude toward the spirit seemed to me highly questionable. Wherever, in a person or in a work of art, an expression of spirituality (in the intellectual, not the supernatural sense) came to light, he suspected it, and insinuated that it was repressed sexuality. Anything that could not be directly interpreted as sexuality he referred to as "psychosexuality."

…There was no mistaking the fact that Freud was emotionally involved in his sexual theory to an extraordinary degree. When he spoke of it, his tone became urgent, almost anxious, and all signs of his normally critical and skeptical manner vanished. A strange, deeply moved expression came over his face, the cause Of which I was at a loss to understand. I had a strong intuition that for him sexuality was a sort of numinosum [this is a term Jung frequently uses to refer to the concepts “spiritual, holy, divine” and also “ethereal, nebulous, intangible.”].

This was confirmed by a conversation which took place some three years later (in, 1910), again in Vienna. I can still recall vividly how Freud said to me, "My dear Jung, promise me never to abandon the sexual theory. That is the most essential thing of all. You see, we must make a dogma of it, an unshakable bulwark." He said that to me with great emotion, the tone of a father saying, "And promise me this one thing, my dear son: that you will go to church every Sunday." In some astonishment I asked him, "A bulwark--against what?" which he replied, "Against the black tide of mud"--and here hesitated for a moment, then added--"Of occultism." First of all, it was the words "bulwark" and "dogma" that alarmed me; for a dogma, that is to say, an undisputable confession of faith is set up only when the aim is to suppress doubts once and for all. But that no longer has anything to do with scientific judgment; only with a personal power drive. This was the thing that struck at the heart of our friendship. I knew that I would never be able to accept such an attitude. What Freud seemed to mean by "Occultism" was virtually everything that philosophy and religion, including the rising contemporary science of parapsychology, had learned about the psyche. To me the sexual theory was just as occult, that is to say, just as unproven an hypothesis, as many other speculative views.

As I saw it, a scientific truth was a hypothesis which might be adequate for the moment but was not to be preserved as an article of faith for all time. Although I did not properly understand it then, I had observed in Freud the eruption of unconscious religious factors. Evidently he wanted my aid in erecting a barrier against these threatening unconscious contents.

The impression this conversation made upon me added to my confusion; until then I had not considered sexuality as a precious and imperiled concept to which one must remain faithful. Sexuality evidently meant more to Freud than to other people. For him it was something to be religiously observed. In the face of such deep convictions one generally becomes shy and reticent. After a few stammering attempts on my part, the conversation soon came to an end. I was bewildered and embarrassed. I had the feeling that I had caught a glimpse of a new, unknown country from which swarms of new ideas flew to meet me. One thing was clear: Freud, who had always made much of his irreligiosity, had now constructed a dogma; or rather, in the place of a jealous God whom he had lost, he had substituted another compelling image, that of sexuality. It was no less insistent, exacting, domineering, threatening, and morally ambivalent than the original one. Just as the psychically stronger agency is given "divine" or "daemonic" attributes, so the "sexual libido" took over the role of a deus absconditus, a hidden or concealed god. The advantage of this transformation for Freud was, apparently, that he was able to regard the new numinous principle as scientifically irreproachable and free from all religious taint. At bottom, however, the numinosity, that is, the psychological qualities of the two rationally incommensurable opposites--Yahweh and sexuality--remained the same. The name alone had changed, and with it, of course, the point of view: the lost god had now to be sought below, not above. But what difference does it make, ultimately, to the stronger agency if it is called now by one name and now by another?

…Freud, sexuality was undoubtedly a numinosum, his terminology and theory seemed to define it exclusively as a biological function. It was only the emotionality with which he spoke of it that revealed the deeper elements reverberating within him. Basically, he wanted to teach--or so at least it seemed to me--that, regarded from within, sexuality included spirituality and had an intrinsic meaning. But his concretistic terminology was too narrow to express this idea. He gave me the impression that at bottom he was working against his own goal and against himself; and there is, after all, no harsher bitterness than that of a person who is his own worst enemy. In his own words, he felt himself menaced by a "black tide of mud"--he who more than anyone else had tried to let down his buckets into those black depths. Freud never asked himself why he was compelled to talk continually of sex, why this idea had taken such possession of him. He remained unaware that his "monotony of interpretation" expressed a flight from himself, or from that other side of him which might perhaps be called mystical. So long as he refused to acknowledge that side, he could never be reconciled with himself. He was blind toward the paradox and ambiguity of the contents of the unconscious, and did not know that everything which arises out of the unconscious has a top and a bottom, an inside and an outside. When we speak of the outside--and that is what Freud did--we are considering only half of the whole, with the result that a countereffect arises out of the unconscious.

There was nothing to be done about this one-sidedness of Freud's. Perhaps some inner experience of his own might have opened his eyes; but then his intellect would have reduced any such experience to "mere sexuality" or "psychosexuality." He remained the victim of the one aspect he could recognize, and for that reason I see him as a tragic figure; for he was a great man, and what is more, a man in the grip of his [demon].

TRAVELS

Jung’s encounters with Freud extend for many years and they are much more involved than this excerpt portrays. Suffice it to say here that for the reasons Jung articulates above he knew that he would never be able to follow Freud or Freud’s ideas as Freud was laying them out to him.

Jung then began an independent search for what he considered, the TRANSCENDENT (although Jung did not use this word specifically). This search led him to travel extensively, I will present a few excerpts of what Jung learned from these travels.

At the beginning of 1920 a friend told me that he had a business trip to make to Tunis, and would I like to accompany him? I said yes immediately. We set out in March, going first to Algiers. Following the coast, we reached Tunis and from there Sousse, where I left my friend to his business affairs.

BACKGROUND TO JUNG’S TRAVELS

What the Europeans regard as Oriental calm and apathy seemed to me a mask; behind it I sensed a restlessness, a degree of agitation, which I could not explain. Strangely, in setting foot upon Moorish soil NOTE: Moorland mostly occur in tropical Africa, northern and western Europe, and neotropical South America), I found myself haunted by an impression which I myself could not understand: I kept thinking that the land smelled queer. It was the smell of blood, as though the soil were soaked with blood. This strip of land, it occurred to me, had already borne the brunt of three civilizations: Carthaginian, Roman, and Christian. What the technological age will do with Islam remains to be seen.

When I left Sousse (Switzerland), I traveled south to Sfax, and thence into the Sahara, to the oasis city of Tozeur. The city lies on a slight elevation, on the margin of a plateau, at whose foot lukewarm, slightly saline springs well up profusely and irrigate the oasis through a thousand little canals. Towering date palms formed a green, shady roof overhead, under which peach, apricot, and fig trees flourished, and beneath these alfalfa of an unbelievable green. Several kingfishers, shining like jewels, flitted through the foliage. In the comparative coolness of this green shade strolled figures clad in white, among them a great number of affectionate couples holding one another in close embrace obviously homosexual friendships. I felt suddenly transported to the times of classical Greece, where this inclination formed the cement of a society of men and of the polls based on that society… These, my dragoman [NOTE: n interpreter or guide, especially in countries speaking Arabic, Turkish, or Persian] explained, were prostitutes. On the main streets the scene was dominated by men and children.

JUNG MOVING INTO A “HEART OF DARKNESS - JOSEPH CONRAD

The deeper we penetrated into the Sahara, the more time slowed down for me; it even threatened to move backward. The shimmering heat waves rising up contributed a good deal to my dreamy state, and when we reached the first palms and dwellings of the oasis, it seemed to me that everything here was exactly the way it should be and the way it had always been.

This scene taught me something: these people live from their affects, are moved and have their being in emotions. Their consciousness takes care of their 'orientation in space and transmits impressions from outside, and it is also stirred by inner impulses and affects. But it is not given to reflection; the ego has almost no autonomy. The situation is not so different with the European; but we are, after all, somewhat more complicated. At any rate the European possesses a certain measure of will and directed intention. What we lack is intensity of life.

DURING THIS PERIOD JUNG HAD MULTIPLE DREAMS AND SPIRITUAL EXPERIENCES INCLUDING MYSTICAL APPARATIONS.

INDIA AND THE CONCEPT OF EVIL

In India I was principally concerned with the question of the psychological nature of evil. I had been very much impressed by the way this problem is integrated in Indian spiritual life, and I saw it in a new light. In a conversation with a cultivated Chinese I was also impressed, again and again, by the fact that these people are able to integrate so-called "evil" without 'losing face." In the West we cannot do this. For the Oriental the problem of morality does not appear to take first place, as it does for us. To the Oriental, good and evil are meaningfully contained in nature, and are merely varying degrees of the same thing. I saw that Indian spirituality contains as much of evil as of good. The Christian strives for good and succumbs to evil; the Indian feels himself to be outside good and evil, and seeks to realize this state by meditation or yoga. My objection is that, given such an attitude, neither good nor evil takes on any real outline, and this produces a certain stasis. One does not really believe in evil, and one does not really believe in good. Good or evil are then regarded at most as my good or my evil, as whatever seems to me good or evil which leaves us with the paradoxical statement that Indian spirituality lacks both evil and good, or is so burdened by contradictions that it needs nirdvandva, the liberation from opposites and from the ten thousand things. The Indian's goal is not moral perfection, but the condition of nirdvandva. He wishes to free himself from nature; in keeping with this aim, he seeks in meditation the condition of imagelessness and emptiness. I, on the other hand, wish to persist in the state of lively contemplation of nature and of the psychic images. I want to be freed neither from human beings, nor from myself, nor from nature; for all these appear to me the greatest of miracles. Nature, the psyche, and life appear to me like divinity unfolded and what more could I wish for? To me the supreme meaning of Being can consist only in the fact that it is, not that it is not or is no longer. To me there is no liberation a tout prix. I cannot be liberated from anything that I do not possess, have not done or experienced. Real liberation becomes possible for me only when I have done all that I was able to do, when I have completely devoted myself to a thing and participated in it to the utmost. If I withdraw from participation, I am virtually amputating the corresponding part of my psyche. Naturally, there may be good reasons for my not immersing myself in a given experience.

But then I am forced to confess my inability, and must know that I may have neglected to do something of vital importance. In this way I make amends for the lack of a positive act by the clear knowledge of my incompetence. A man who has not passed through the inferno of his passions has never overcome them. They then dwell in the house next door, and at any moment a flame may dart out and set fire to his own house. Whenever we give up, leave behind, and forget too much, there is always the danger that the things we have neglected will return with added force.

JUNG’S FIRST MAJOR DREAM

Jung was a vivid recorder of dreams, his own and the dreams of his patients. He not only vividly recalled dreams (perhaps a special capability) but he was also so enamored with dreams, that he focused on them throughout his life. It is hard to know, from Jung’s writings, what Jung ultimately believed that dreams could reveal, but they are clearly a major feature of his psychotherapeutic approach. To my knowledge, this was the first fully constituted dream that Jung refers back to many times as a guiding feature of his life. This is why I am presenting the dream in its complete form here. He had this dream following a serious illness of dysentery where he spent 10 days in the hospital in Calcutta, India. It is unclear if this dream is a natural phenomenon or a product of delirium for Jung.

DREAM #1

When I returned to the hotel, in tolerably good health, I had a dream so characteristic that I wish to set it down here. I found myself, with a large number of my Zurich friends and acquaintances, on an unknown island, presumably situated not far off the coast of southern England. It was small and almost uninhabited. The island was narrow, a strip of land about twenty miles long, running in a north-south direction. On the rocky coast at the southern end of the island was a medieval castle…We stood in its courtyard, a group of sightseeing tourists.

Before us rose an imposing 'belfroi', through whose gate a wide stone staircase was visible. We could just manage to see that it terminated above in a columned hall. This hall was dimly illuminated by candlelight. I understood that this was the castle of the Grail, and that this evening there would be a "celebration of the Grail" here. This information seemed to be of a secret character, for a German professor among us, who strikingly resembled old Mommsen, knew nothing about it. I talked most animatedly with him, and was impressed by his learning and sparkling intelligence. Only one thing disturbed me: he spoke constantly about a dead past and lectured very learnedly on the relationship of the British to the French sources of the Grail story. Apparently he was not conscious of the meaning of the legend, nor of its living presentness, whereas I was intensely aware of both. Also, he did not seem to perceive our immediate, actual surroundings, for he behaved as though he were in a classroom, lecturing to his students. In vain I tried to call his attention to the peculiarity of the situation. He did not see the stairs or the festive glow in the hall.

I looked around somewhat helplessly, and discovered that I was standing by the wall of a tall castle; the lower portion of the wall was covered by a kind of trellis, not made of the usual wood, but of black iron artfully formed into a grapevine complete with leaves, twining tendrils, and grapes. At intervals of six feet on the horizontal branches were tiny houses, likewise of iron, like birdhouses. Suddenly I saw a movement in the foliage; at first it seemed to be that of a mouse, but then I saw distinctly a tiny, iron, hooded gnome, a cucullatus, scurrying from one little house to the next. "Well," I exclaimed in astonishment to the professor, "now look at that, will you..." At that moment a hiatus occurred, and the dream changed. We--the same company as before, but without the professor-- were outside the castle, in a treeless, rocky landscape. I knew that something had to happen, for the Grail was not yet in the castle and still had to be celebrated that same evening. It was said to be in the northern part of the island, hidden in a small, uninhabited house, the only house there. I knew that it was our task to bring the Grail to the castle. There were about six of us who set out and tramped northward. After several hours of strenuous hiking, we reached the narrowest part of the island, and I discovered that the island was actually divided into two halves by an arm of the sea. At the smallest part of this strait the width of the water was about a hundred yards. The sun had set, and night descended. Wearily, we camped on the ground. The region was unpopulated and desolate; far and wide there was not a tree or shrub, nothing but grass and rocks. There was no bridge, no boat. It was very cold; my companions fell asleep, one after the other. I considered what could be done, and came to the conclusion that I alone must swim across the channel and fetch the Grail. I took off my clothes. At that point I awoke. Here was this essentially European dream emerging when I had barely worked my way out of the overwhelming mass of Indian impressions. Some ten years before, I had discovered that in many places in England the myth of the Grail was still a living thing, in spite of all the scholarship that has accumulated around this tradition. This fact had impressed me all the more when I realized the concordance between this poetic myth and what alchemy had to say about the unum vas, the una medicina, and the unus lapis. Myths which day has forgotten continue to be told by night, and powerful figures which consciousness has reduced to banality and ridiculous triviality are recognized again by poets and prophetically revived; therefore they can also be recognized "in changed form" by the thoughtful person. The great ones of the past have not died, as we think; they have merely changed their names. "Small and slight, but great in might," the veiled Kabir enters a new house. Imperiously, the dream wiped away all the intense impressions of India and swept me back to the too-long-neglected concerns of the Occident NOTE: the Occident here, refers to Jung’s work in Europe), which had formerly been expressed in the quest for the Holy Grail as well as in the search for the philosophers' stone. I was taken out of the world of India, and reminded that India was not my task, but only a part of the way --admittedly a significant one which should carry me closer to my goal. It was as though the dream were asking me, "What are you doing in India? Rather seek for yourself and your fellows the healing vessel, the servator mundi, which you urgently need. For your state is perilous; you are all in imminent danger of destroying all that centuries have built up."

Jung, throughout his life, from this point forward, writes that he was the recipient of VISIONS. It is hard to determine the nature of Jung’s Visionary Experiences, but he was clearly in tune to these kinds of supernatural experiences. He believed them to be real, and from time to time he presents evidence to demonstrate the prescience of his dream experiences. But, then, he hedges. Jung is always hedging, being careful to become too dogmatic in his thoughts and beliefs. Through all his experiences, Jung tries to maintain a subtle objectivism, but it is clear, at least as I read his multiple works, that he, himself, was a true believed, of sorts in the power and validity of myth, particularly ancient, primordial myth.

Some of Jung’s experiences were tied to reality and particularly the objective future, not only his future and the future of individual patients or friends, but the future of the entire world. EXAMPLE: He believed that some of his Visions foretold events like the First and Second World Wars. there were times that he saw the future of another individual, like the Doctor who treated him for a heart attack. As noted in this example below, he foresaw (at least this is how he presents it) the doctor’s ultimate death. So, Jung’s view of the TRANSCENDENT interacted in a real and demonstrable way to Jung’s reality.

JUNG’S VISION

At the beginning of 1944 I broke my foot, and this misadventure was followed by a heart attack. In a state of unconsciousness I experienced deliriums and visions which must have begun when I hung on the edge of death and was being given oxygen and camphor injections. The images were so tremendous that I myself concluded that I was close to death. My nurse afterward told me, "It was as if you were surrounded by a bright glow" That was a phenomenon she had sometimes observed in the dying, she added. I had reached the outermost limit, and do not know whether I was in a dream or an ecstasy. At any rate, extremely strange things began to happen to me.

It seemed to me that I was high up in space. Far below I saw the globe of the earth, bathed in a gloriously blue light. I saw the deep blue sea and the continents. Far below my feet lay Ceylon, and in the distance ahead of me the subcontinent of India. My field of vision did not include the whole earth, but its global shape was plainly distinguishable and its outlines shone with a silvery gleam through that wonderful blue light. In many places the globe seemed colored, or spotted dark green like oxydized silver. Far away to the left lay a broad expanse the reddish-yellow desert of Arabia; it was as though the silver of the earth had there assumed a reddish-gold hue. Then came the Red Sea, and far, far back as if in the upper left of a map I could just make out a bit of the Mediterranean. My gaze was directed chiefly toward that. Everything else appeared indistinct. I could also see the snow-covered Himalayas, but in that direction it was foggy or cloudy. I did not look to the right at all. I knew that I was on the point of departing from the earth. Later

[HERE IS AN EXAMPLE OF JUNG INSERTING HIS OBJECTIVISM INTO THE VISION] “I discovered how high in space one would have to be to have so extensive a view approximately a thousand miles! The sight of the earth from this height was the most glorious thing I had ever seen.”

While I was thinking over these matters, something happened that caught my attention. From below, from the direction of Europe, an image floated up. It was my doctor, Dr. H. or, rather, his likeness framed by a golden chain or a golden laurel wreath. I knew at once: "Aha, this is my doctor, of course, the one who has been treating me. But now he is coming in his primal form…In life he was an avatar of this basileus, the temporal embodiment of the primal form, which has existed from the beginning. Now he is appearing in that primal form". Presumably I too was in my primal form, though this was something I did not observe but simply took for granted. As he stood before me, a mute exchange of thought took place between us. Dr. H. had been delegated by the earth to deliver a message to me, to tell me that there was a protest against my going away, I had no right to leave the earth and must return.

The moment I heard that, the vision ceased. I was profoundly disappointed, for now it all seemed to have been for nothing. The painful process of defoliation had been in vain, and I was not to be allowed to enter the temple, to join the people in whose company I belonged. In reality, a good three weeks were still to pass before I could truly make up my mind to live again. I could not eat because all food repelled me. The view of city and mountains from my sickbed seemed to me like a painted curtain with black holes in it, or a tattered sheet of newspaper full of photographs that meant nothing. Disappointed, I thought, "Now I must return to the 'box system' again." For it seemed to me as if behind the horizon of the cosmos a three-dimensional world had been artificially built up, in which each person sat by himself in a little box. And now I should have to convince myself all over again that this was important! Life and the whole world struck me as a prison, and it bothered me beyond measure that I should again be finding all that quite in order. I had been so glad to shed it all, and now it had come about that I along with everyone else would again be hung up in a box by a thread. While I floated in space, I had been weightless, and there had been nothing tugging at me. And now all that was to be a thing of the past! 1 Basileus king. Kos was famous in antiquity as the site of the temple of Asklepios, and was the birthplace of Hippocrates. A. J. I felt violent resistance to my doctor because he had brought me back to life. At the same time, I was worried about him. "His life is in danger, for heaven's sake! He has appeared to me in his primal form! When anybody attains this form it means he is going to die, for already he belongs to the 'greater company'!" Suddenly the terrifying thought came to me that Dr. H. would have to die in my stead. I tried my best to talk to him about it, but he did not understand me. Then I became angry with him. "Why does he always pretend he doesn't know he is a basileus of Kos? And that he has already assumed his primal form? He wants to make me believe that he doesn't know!" That irritated me. My wife reproved me for being so unfriendly to him. She was right; but at the time I was angry with him for stubbornly refusing to speak of all that had passed between us in my vision. "Damn it all, he ought to watch his step. He has no right to be so reckless! I want to tell him to take care of himself." [EXAMPLE OF JUNG’S VISION PREDICTING THE FUTURE OF ANOTHER PERSON] I was firmly convinced that his life was in jeopardy. In actual fact I was his last patient. On April 4, 1944 I still remember the exact date I was allowed to sit up on the edge of my bed for the first time since the beginning of my illness, and on this same day Dr. H. took to his bed and did not leave it again. I heard that he was having intermittent attacks of fever. Soon afterward he died of septicemia. He was a good doctor; there was something of the genius about him. Otherwise he would not have appeared to me as a prince of Kos.

All these experiences were glorious. Night after night I floated in a state of purest bliss, "thronged round with images of all creation." [3] Gradually, the motifs mingled and paled. Usually the visions lasted for about an hour; then I would fall asleep again. By the time morning drew near, I would feel: Now gray morning is coming again; now comes the gray world with its boxes! What idiocy, what hideous nonsense! Those inner states were so fantastically beautiful that by comparison this world appeared downright ridiculous. As I approached closer to life again, they grew fainter, and scarcely three weeks after the first vision they ceased altogether…In Cabbalistic doctrine Malchuth and Tifereth are two of the ten spheres of divine manifestation in which God emerges from his hidden state. They represent the female and male principles within the Godhead…They were the most tremendous things I have ever experienced. And what a contrast the day was: I was tormented and on edge; everything irritated me; everything was too material, too crude and clumsy, terribly limited both spatially and spiritually. It was all an imprisonment, for reasons impossible to divine, and yet it had a kind of hypnotic power, a cogency, as if it were reality itself, for all that I had clearly perceived its emptiness. Although my belief in the world returned to me, I have never since entirely freed myself of the impression that this life is a segment of existence which is enacted in a three-dimensional box-like universe especially set up for it.

I would never have imagined that any such experience was possible. It was not a product of imagination. The visions and experiences were utterly real; there was nothing subjective about them; they all had a quality of absolute objectivity. We shy away from the word "eternal," but I can describe the experience only as the ecstasy of a non-temporal state in which present, past, and future are one. Everything that happens in time had been brought together into a concrete whole. Nothing was distributed over time, nothing could be measured by temporal concepts. The experience might best be defined as a state of feeling, but one which cannot be produced by imagination. How can I imagine that I exist simultaneously the day before yesterday, today, and the day after tomorrow? There would be things which would not yet have begun, other things which would be indubitably present, and others again which would already be finished and yet all this would be one. The only thing that feeling could grasp would be a sum, an iridescent whole, containing all at once expectation of a beginning, surprise at what is now happening, and satisfaction or disappointment with the result of what has happened. One is interwoven into an indescribable whole and yet observes it with complete objectivity.

JUNG AND LIFE AFTER DEATH

Jung did a great deal of thinking about life after death. For the most part, he characterized his thinking within mythology and symbolism, which, according to Jung, if a person is able to open him or herself up to this way of experiencing and feeling, then insight can be drawn from it. Otherwise, our rational, objective, culturally-constrained way of thinking tends to nullify this capability. It is clear that TRANSENDENTAL perceiving is within the capacity of the human psyche.

What I have to tell about…life after death, consists entirely of memories, of images in which I have lived and of thoughts which have buffeted me. These memories in a way also underlie my works; for the latter are fundamentally nothing but attempts, ever renewed, to give an answer to the question of the interplay between the "here" and the "hereafter." Yet I have never written expressly about a life after death; for then I would have had to document my ideas, and I have no way of doing that. Be that as it may, I would like to state my ideas now. Even now I can do no more than tell stories "mythologize." Perhaps one has to be close to death to acquire the necessary freedom to talk about it. It is not that I wish we had a life after death. In fact, I would prefer not to foster such ideas. Still, I must state, to give reality its due, that, without my wishing and without my doing anything about it, thoughts of this nature move about within me. I can't say whether these thoughts are true or false, but I do know they are there, and can be given utterance, if I do not repress them out of some prejudice. Prejudice cripples and injures the full phenomenon of psychic life. And I know too little about psychic life to feel that I can set it right out of superior knowledge. Critical rationalism has apparently eliminated, along with so many other mythic conceptions, the idea of life after death. This could only have happened because nowadays most people identify themselves almost exclusively with their consciousness, and imagine that they are only what they know about themselves. Yet anyone with even a smattering of psychology can see how limited this knowledge is. Rationalism and doctrinairism are the disease of our time; they pretend to have all the answers. But a great deal will yet be discovered which our present limited view would have ruled out as impossible. Our concepts of space and time have only approximate validity, and there is therefore a wide field for minor and major deviations. In view of all this, I lend an attentive ear to the strange myths of the psyche, and take a careful look at the varied events that come my way, regardless of whether or not they fit in with my theoretical postulates. Unfortunately, the mythic side of man is given short shrift nowadays. He can no longer create fables. As a result, a great deal escapes him; for it is important and salutary to speak also of incomprehensible things. Such talk is like the telling of a good ghost story, as we sit by the fireside and smoke a pipe. What the myths or stories about a life after death really mean, or what kind of reality lies behind them, we certainly do not know. We cannot tell whether they possess any validity beyond their indubitable value as anthropomorphic projections. Rather, we must hold clearly in mind that there is no possible way for us to attain certainty concerning things which pass our understanding.

We cannot visualize another world ruled by quite other laws, the reason being that we live in a specific world which has helped to shape our minds and establish our basic psychic conditions. We are strictly limited by our innate structure and therefore bound by our whole being and thinking to this world of ours. Mythic man, to be sure, demands a "going beyond all that" but scientific man cannot permit this. To the intellect, all my mythologizing is futile speculation. To the emotions, however, it is a healing and valid activity; it gives existence a glamour which we would not like to do without. Nor is there any good reason why we should.

For me, Jung is among the six or so human beings who worked very hard to think beyond the simple-minded paradigms of human understanding and reason. He was also not entirely caught up in “blind belief.” He tried, very hard, to keep an open mind to alternate possibilities for understanding human existence.

To be sure, Jung clearly did much more thinking about the transcendent and how to tap into it. In fact, if I expanded further this entry, I could show how his writings evolved to build the idea of transcendence into his psychotherapeutic work. In the end, however, Jung was only a person living on this earth who was substantially curious about the meaning of human existence. I do not think he had supernatural powers or abilities, nor do I think that Jung was divinely destined to reveal things of a prophetic nature to human beings, generally. His purpose was basically his life and his experiences. He was gifted at recording his experiences and doing so in as unbiased a way as possible. So, it could be Jung found in his own way and through Jung’s own efforts discovered hidden pathways to extra-sensory understanding. This makes his work and writings worth attending to.

I will conclude this entry for now on a final statement made by Jung.

Our age [the 1950’s and 1960’s] has shifted all emphasis to the here and now, and thus brought about a demonization of man and his world. The phenomenon of dictators and all the misery they have wrought springs from the fact that man has been robbed of transcendence by the shortsightedness of the super-intellectuals. Like them, he has fallen a victim to unconsciousness. But man's task is the exact opposite: to become conscious of the contents that press upward from the unconscious. Neither should [man] persist in his unconsciousness, nor remain identical with the unconscious elements of his being, thus evading his destiny, which is to create more and more consciousness. As far as we can discern, the sole purpose of human existence is to kindle a light in the darkness of mere being. It may even be assumed that just as the unconscious affects us, so the increase in our consciousness affects the unconscious.

ENTRY ENDED 12-22-2021, WILL RETURN AT A LATER DATE.