In psychopathology, “OBSESSION” is prominent.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

Obsessive-Compulsive-Personality-Disorder (OCPD)

Obsessive THOUGHTS AND FEELINGS

Obsessive thinking and feeling are endemic in psychiatric disorders.”

Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD): - Obsessive preoccupation with perceived defects or flaws in one’s physical appearance.

Hoarding Disorder: Obsessive preoccupation with possessions due to a perceived need to save them.

Eating Disorder: Obsessive preoccupation with food, body weight, or body image.

Substance Abuse Disorder: Obsessive preoccupation with substances of abuse.

Psychotic Disorder: Overwhelming obsessions in response to delusions or hallucinations.

Hypochondria: Obsessive thinking about anxiety about one's health and unwarranted fear that one has a severe disease.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD): Obsessive worry about the future and everyday events.

Obsessions are in literature, such as “Magnificent Obsession” by Lloyd C. Douglas, and in plays like “Dangerous Obsession” by N.J. Crisp, as well as in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.

Some say they know what obsessions are.

Why?

Because they’ve experienced one.

Some people are known for being obsessed.

Artists

Enemies

The Mentally Ill

The Rich

Lovers

Madmen

Leaders

Inventors

There are movies about obsessive men and/or women whose lives,

And the lives of the “obsessed-with” are ruined by it.

There are instances where obsessive feeling states are facilitating, but then turn to overwhelming, negative, unreasonable, and catastrophically damaging.

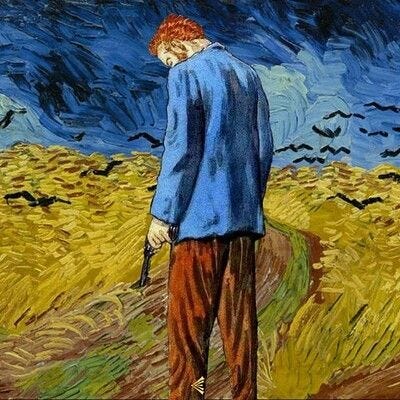

Van Gogh’s obsession with what he saw in color and form is a case in point.

He described one as a “colorific glow” of images and scenes, another obsession as pure colors that overwhelmed his emotions. “I am crazy about two colors: carmine and cobalt…cobalt is a divine color.”

The painting above, a Van Gogh self-portrait, was made during a period of intense emotional turmoil.

Below is a Van Gogh scene made at Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, a psychiatric asylum in nearby Saint-Rémy-de-Provence (note the Catholic Nuns). This was painted after he voluntarily checked himself into the asylum.

At that time, May 8, 1889, his condition was diagnosed as epilepsy. Treatment: “Rest.”

Uncontrollable obsessions drove van Gogh’s life, combined with alcoholism, into a mental condition that probably appeared like epilepsy.

At their florid worst, obsessions contributed to his suicide by gunshot to the chest.

As an inpatient and outpatient psychologist, I’ve dealt with obsessions, paranoid obsessions, obsessive love triangles, obsessive fears, and obsessive hatreds, to name a few.

I’ve observed obsessions in substantial mental illness, including in healthy individuals, except for an overwhelming obsession.

I’ve had personal experiences with obsession.

Dr. Hill, are you saying you are mentally ill?

I’m telling you that our capability and tendency to experience obsessions are baked into our human makeup, as an extension of our passions.

If you have ever been “madly in love,” and in such a state, you can’t see the “forest for the trees,” you are in an obsession of your own making.

Falling in love is inherently obsessive, at least at first. It certainly isn’t rational.

Obsessions are not only complex but also challenging to understand.

When do you recall enduring an obsessive thought or feeling?

Have you acted on it?

If so, what happened?

What is an Obsession?

The dictionary (Merriam-Webster) defines “obsession” as 1: a persistent, disturbing preoccupation with an often unreasonable idea or feeling… (example: an obsession with a movie star) 2: something that causes an obsession (example: Losing weight can be an obsession that results in the avoidance of certain foods.)

The American Psychological Association Dictionary elaborates: obsession (n) a persistent thought, idea, image, or impulse that is experienced as intrusive or inappropriate and results in marked anxiety, distress, or discomfort. Obsessions are often described as ego-dystonic, [meaning] they are experienced as alien or inconsistent with one’s self and outside one’s control (although this is not necessarily the case in children). Common obsessions include repeated thoughts about contamination, a need to have things in a particular order or sequence, repeated doubts, aggressive or horrific impulses, and sexual imagery. Obsessions can be distinguished from excessive worries about everyday occurrences in that they are not concerned with real-life problems…

Merriam-Webster

links “obsession” to “preoccupation.”

labels them as a thinking problem.

characterizes them as abnormal or unreasonable (most of the time).

The APA definition assumes an obsession is:

A thought, idea, image, or an impulse experienced as intrusive or inappropriate.

Results in anxiety, distress, or discomfort.

Ego-dystonic or alien to oneself, and consequently, resistant to self-control.

Pathological.

Not an everyday worry.

Not concerned with real-life problems.

Why does the APA Dictionary “exclude” children? (I’ll describe this at the end.)

Some say that the only way to understand an obsession (or a profound and unreasonable preoccupation with something unattainable) is to experience it.

It’s difficult to feel or think about anything else while in an obsessive state. Recall Van Gogh.

At the same time, obsessions are maddeningly elusive. Although some seem convincingly obtainable, obsessions only exist in the realm of the fantastic or as a product of our imaginative mind, wishes, dreams, and passion. Many times, obsessions tell us that these are our needs and, in some way, unfulfilled.

The more elaborate your imaginative mind, the stronger your obsessive tendencies.

People who struggle with obsessive thoughts tend to be hypnotizable.

From Whence Do Obsessions Come?

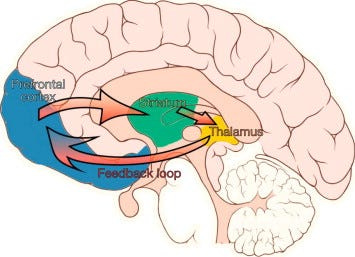

The capacity to experience an obsession is initiated in the brain.

Evidence of rapid activation in targeted brain areas during an obsession has been found.

This includes the prefrontal cortex (PFC), basal ganglia, striatum, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), the thalamus, and caudate nucleus.

Studies in the neurobiology of obsessions are usually conducted in persons with psychopathology, for example, between OCD patients and controls.

I was not able to find credible research where “obsessive only” patients were contrasted to non-obsessive controls, which makes it difficult for me to disentangle obsessions and compulsions using neuroscience research.

Either way, neuronal transmission within and across brain structures cycles and such cycles become tighter during an obsession.

This activation cycle (or loop) has been identified and measured.

There is no psychological theory devoted to the “obsessive state.”

Instead, obsessions are studied in conjunction with other psychiatric conditions, such as Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder.

There are instances when obsession is used to emphasize a core feature of a psychiatric disorder—the obsessive preoccupation with oneself in narcissistic personality disorder (NPD).

“Self-obsession” or an exaggerated hedonism combined with obsessive self-focus, with manipulative tendencies, is a primary feature of narcissistic personality disorder (NPD). Combined with the radical compliance of many of the narcissist’s victims, NPD is nearly impossible to treat.

The Case of Eric

(This extended case explores the intrapsychic features of obsessiveness)

(Public domain image for illustration)

Feel free to skip this case if it seems too involved.

Eric was a 68-year-old, college-educated, White male, divorced, with no biological children. He was an air-traffic controller, which he claimed caused him traumatic stress and destroyed his marriage.

After his divorce, Eric lost many of his friends.

The people he knew at that time, as he described them, were entangled in his old marriage and lost to him when he divorced.

He had some longstanding friendships from his work and a few close buddies from the military.

Eric grew up in the Midwest and spent most of his adolescence and early adulthood there.

While married, he and his spouse, Darlene (whom he met in high school), vacationed in Utah where they learned to ski, and it was here that Eric became enamored with the sport.

Most holidays afterwards were spent there. After the divorce, Eric relocated to Utah.

His parents had both passed, leaving Eric a sizable inheritance that was split between him and his sister, Edna.

About five years before our first visit, Eric reported low-grade, but persistent fear that he was destined for loneliness and disconnection in old age. As he grew older, his worry intensified.

He lamented that because his spouse had a medical condition that prohibited pregnancy, he had no children. “Doc, kids slipped by me for no fault of my own.”

With these fears, Eric began to open his mind to a long-term partner.

But how, or who, or where?

As I got to know Eric, I wondered how much he understood about the nature of love and living with someone. At his mature age, he was set in his ways, had strong tendencies towards selfishness and was one-sided in his thinking.

He saw himself as a victim of circumstance and avoided taking responsibility for his current life situation. “Doc, I got a raw deal and I’m doing what I can to make the best of it.”

Eric started looking into internet dating sites, and hired a company, “The Loving Connection Group,” to “match” him with women seeking long-term companions.

Eric noted that most of these women “were too baggy and too naggy” to marry.

One day, while in the supermarket he struck up a conversation with a woman. Eric said she was “attractive for her age.” She asked him for help to reach some cans on a top shelf (Eric was 6’2” tall). Eric obliged, after which they had a short, friendly conversation. Then the woman did something unusual. She asked Eric for a hug.

He cautiously consented. Eric said, “Doc, it was just an, innocent hug, but I felt her body, and it was exhilarating!” Then, the woman said, “Thanks for the help, I hope we run into each other in the future.” She pushed her cart away, and Eric never saw her again.

In relating the story to me, Eric remarked:

“I’ve never felt that way about anybody in my life. Doc, I think that woman was my soulmate. I should have gotten her phone number.”

Eric couldn’t stop thinking about this woman (rumination is usually a component of an obsession). He would go over and over in his mind the scant image he recalled of her, and, of course, the hug.

Eric would masturbate to this image, which intensified his desire to find her.

He returned to the supermarket, but she never appeared. Eric was caught in a full-blown obsession.

He wondered if it was healthy to be so preoccupied with this unknown woman. He hired an artist to create a pencil sketch of her portrait, which he showed me—a beautiful and feminine face that appeared to be around 30 years of age.

Eric began losing sleep over this obsession, dreaming of her at night and thinking of her during the day. He came up with unusual ideas to find her, such as going through the grocery store receipts to locate the time and date of their previous interaction in a visa or check record where he might find her name or address.

Eric spent hours searching the internet for her face (this was before the advent of AI). And, of course, a lot of time at that grocery store. Inside, in the parking lot, sitting in his car, watching people pass. All to no avail.

Within the crucible of this obsession, Eric started developing troubling symptoms of distress such as chronic despondency, poor future outlook, sadness at times for no reason, irritability with himself and others, and enhanced loneliness.

Was Eric’s Preoccupation with the “unknown grocery woman” an obsession?

If so, Why?

How does one address the negative impacts of “obsessive desire?”

Eric describes an event that exhibits compelling obsessive characteristics: 1. recurrent and persistent thoughts around an emotional theme, and 1a. accompanied by a profound desire (in this case) to be part of (or intertwined with) the object of obsessive desire. 2. Ruminative cycling that reinforces the obsessive thought, 3. distress associated with the desired/hated object of obsession, and 4. elation or positivity about an idealized resolution of the obsessive state into reality (“living happily ever after”).

Does Eric’s case fit this description?

If so, was Eric born with this obsessive tendency?

Or did he acquire it through life?

Some might say Eric was unhappy most of his life, and therefore, used obsessive feelings to distract him from his existential misery.

Will Eric ever recover from obsessive thinking?

Or

Will he be chasing the “woman in the grocery store” image the rest of his natural life?

In my experience, the answer is NO.

Eric’s eventual decision to move out of Utah was a good one for him. He said he wanted a new experience. At first it was puzzling given this, that he ultimately moved back to his hometown.

Why?

His hometown is where Eric is likely to regress to a maturity level similar to that of his earlier years.

His growing maturity in Utah was challenged by something within him that predisposed him to an obsessive event. Eric unconsciously used the obsessive state to push his physical return to a familiar world where he could address the larger issue of “fear of loneliness” or “age-related dependency.”

Eric was, in reality, homesick, but dealing with this directly was not consciously possible (at least for him), given his limited maturity and male, military persona, so he created (subconsciously) an intermediary state that led, pushed him circuitously, to an eventual move back to his hometown. By going home, Eric escapes his obsessive feelings.

In a sense, Eric’s obsession was telling him something about his needs, and although Eric did not fully understand it, he acted accordingly to preserve his well-being.

This was by leaving his recreation paradise and moving home. Eric will essentially be back in a situation where finding a long-term companion will be easier, given that Iowans are “his people,” those with whom he is familiar and can live comfortably with in his old age.

Unbeknownst to him, and through the power of his obsession, Eric was treating himself by returning to his roots for the emotional support he needed.

What are the takeaways from this entry on Obsessiveness?

Obsessiveness is a natural part of every human being’s biological makeup. An obsession may feel like a foreign force when you experience one, but it is only you; your psyche, mind, unconscious, and emotions working to adapt to your circumstances. In this sense, obsessiveness is not to be feared, but UNDERSTOOD. Ask yourself, What is the message of my obsession? Think of the “Eric” case. What was his obsessive state telling him?

Standard medical treatment for obsession is to get rid of it, dampen it, or diminish it. Frequently this is done with medication. Sometimes, distraction is used. There are pros and cons to this approach. Medication might help you feel temporarily better, but obsessions, unresolved, usually return. My approach is to identify what lies at the root of an obsessive state. It is almost always NOT the actual object of the obsession, but something else. Frequently, something very unlikely. Like “homesickness” in the case of Eric. I’m not saying that this underlying feature can always be discerned, but it is worth trying to find it before attacking and destroying the symptom (because this doesn’t work either).

Obsessiveness is developmental. Children experience obsessive states all the time, especially before the age of 5 years, when inhibition is not fully developed. “Daddy, I want to be President or an Astronaut. I want a rocket for Christmas.”

Obsessiveness is deeply connected with our faculty for curiosity and wonder, it is an amplification feature of our desires and emotions. Children are given more permission than adults to be curious, desirous, and passionate about something new. This is why we provide childhood obsessiveness a “normal pass,” but treat adult obsessiveness as pathological. We can thank the media for this.

There is a fundamental problem in our paradigm of obsession in this regard. My space has ended, so I will describe this idea further in future posts.