A real-life story.

It goes like this…

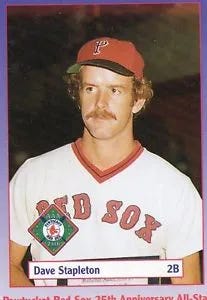

During a Major League Baseball game between the Red Sox and White Sox at Fenway Park on August 7, 1982, Dave Stapleton, a Red Sox player, was at bat when he hit a foul ball.

It flew into the stands and struck a 4-year-old boy named Jonathan Keane in the head, knocking him unconscious. Jonathan was sitting in the foul-ball section with his parents near the front row.

A Boston left fielder, Jim Rice, observing the event from the dugout, ran onto the field and into the stands, found Kean, and carried him into the players’ clubhouse for treatment.

Seeing what happened, Stapleton was frozen in shock.

Despite having hit numerous foul balls into the stands during his career, Stapleton had never experienced anything like this.

The incident drew national attention and had a lasting impact on Stapleton.

Racked with guilt and sorrow over the foul ball, Stapleton visited Kean several times while Kean was recovering.

After the incident, Stapleton felt he could no longer play the game, left professional baseball, moved to North Carolina, enrolled at NC State, and started a new life.

Is Dave Stapleton guilty or innocent of the damages from this batting accident?

Is Dave Stapleton in any way responsible for the harm that was done to Jonathan Kean?

Should Dave Stapleton “feel” guilty for what happened?

If not, should anyone feel responsible?

Should the pitcher feel guilty of throwing the ball in such a way that when Stapleton hit it, the trajectory was towards the boy?

Should the city of Boston feel guilty of not making protective ball nets high enough?

How would you assess this event and Dave Stapleton’s decision to leave baseball?

This is “MORAL LUCK.”

You’ve probably never heard of “Moral Luck.” If you have, you are likely a philosopher.

It is not a phrase commonly used in public discourse. It does, however, have a place as an ironic (or exceptional) real-life event that can happen any time to anyone.

MORAL LUCK is found in psychology and psychotherapy, where it is occasionally encountered, sometimes resulting in guilt or a negative feeling state associated with people who perceive themselves as having engaged in wrongdoing when what went wrong wasn’t their fault.

What is “Moral Luck”?

"Moral luck" refers to situations where someone is judged morally (praised or blamed) for an action and/or its consequences, even though the person had limited or no control over a particular action associated with the result.

It is helpful to define two terms:

Moral

Moral is concerned with the principles of right and wrong and the perceived goodness or badness of human character.

Luck is defined as chance or happenstance, referring to an event that occurs unexpectedly and seemingly without cause. Perhaps a result of fate. Luck is not causally due to anything someone did to bring it about.

Religions (especially fundamentalists) do not view luck “as a determining force,” as doing so de-emphasizes God's sovereignty and control over everything.

Abandoning luck in this way, God’s Will supersedes everything, “… It’s in God’s Hands.”

This “Fundamentalist” viewpoint can result in problems with the application of religion to reality, especially when “bad things happen to good people.”

Emmanuel Kant (a continental philosopher) thought that luck should influence ethics.

Luck is an ethical “free pass.” If, according to Kant, every action is viewed in moral terms, such actions must be “freely performed.”

By this, a person should not be held morally (or ethically) responsible for anything outside one’s control. This has led philosophers to create the

Control Principle: “We are morally accountable only to the extent that what we are assessed for depends on factors under our control.”

In the foul ball incident, applying the Control Principle, Stapleton is not obliged to feel guilty that the ball hit Jonathan Keane. Sad, yes, guilty, no.

“Moral Luck” should not exist given the Control Principle, but this is not what happens in real life. Thomas Nagel (1979, 59) reinstates the idea of Moral Luck in his definition:

“Moral Luck occurs when an agent can be correctly treated as an object of moral judgment, even though a significant aspect of what he is assessed for depends on factors beyond his control.”

Nagel may be denying the obvious. Still, as a psychotherapist, I’ve observed what might be called the phenomenon of moral luck on numerous occasions when the situation of who is or isn’t in control is less clear.

I’ve abstracted this story from the New Yorker magazine by Alice Gregory.

NEW YORKER ARTICLE, EXCERPTED:

Alice Gregory, September 11, 2017

Maryann Gray was happy. She was twenty-two and had just decided to take a leave of absence from Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, where she was pursuing a master’s degree in clinical psychology…That summer, Gray was preparing to move into a ramshackle Victorian mansion in a neglected area of Cincinnati…Gray couldn’t wait to move in. She spent the day painting her new bedroom yellow.

…The hot, hour-long drive crossed through suburban sprawl and then into emerald countryside. Gray had the windows of her father’s 1969 Mercury Cougar down, and the radio tuned to the news. She was only fifteen minutes from the apartment, driving at the posted forty-five miles per hour along a wooded, two-lane country road, when she saw a pale flash and felt a bump.

The statement Gray gave to the police later that afternoon is written in the neat script a young student might use on a final exam: “A child (blond male) ran into the street from my left, running in front of the car. I tried to go around him (to the left) but couldn’t get by. I hit my brakes instantly + skidded to the left.” …

When Gray read the affidavit forty years later, she was surprised by the precision of her account. “There was no way I actually remembered that,” she told me. “Hitting him, I remember, and I remember sort of pulling over on a side street, getting out of the car, and there I lose a few minutes,” Gray recalled, crouching behind a bush, terrified and hiding. “I remember thinking, What’s that noise?, and then realizing it was me, screaming.” She was still concealed by the shrubbery when the boy’s mother ran out of her house and began to wail. “She was with two women, and her knees buckled. She began to fall, and they held her up,” Gray said. “She wanted to go to him, of course, but they held her back.”

The police arrived about twenty minutes later, and, rather than wait for an ambulance, they put the boy in the back seat of a squad car and drove him six miles to the hospital, where, Gray later learned, he was pronounced dead on arrival. Only after the boy had been taken away from the bloodied road did Gray emerge. A few policemen had stayed behind, and she approached them, with one hand raised. “Like a schoolgirl,” Gray recalled. “I was so young.” Her voice caught. “I said, ‘I did it. I did it.”

She was ushered into the back of a police car, where she sat until a woman who lived nearby approached, offered her a cool towel, and asked an officer if Gray could wait at her house instead. The officer agreed, and Gray sat in the kind stranger’s kitchen, sipping water. It was early evening by the time the Butler County sheriff’s office finished its site evaluation and asked Gray if she would be O.K. driving home. She said no. A professor picked her up and persuaded her to call her parents in New York. “I said, ‘Mommy, Mommy’—and I never called her that—‘it was an accident,’ ” Gray recalled. Her mother replied, “Of course it was.”

Gray’s father flew out and took care of logistics…Gray spent the week refusing to leave her old bedroom. “I had what I now consider to be a hallucination,” she told me. “I heard this voice, so clearly, saying, ‘You took a son from his mother and your punishment is that you can never have your own child.’ ” She told her therapist, whom she had been seeing for two years, that she was afraid the accident would ruin her forever.

In the following months, Gray drove slowly and uncertainly. She would see vague figures in the road, slam on the brakes, and then realize that nobody was there. An insect hitting the windshield could send her into a panic. She didn’t know how to act around her new roommates, who treated her with a kind of hesitant benevolence. “Here I was in this house that was all about peace and love and community, and I had just killed a kid,” Gray said. “I really wanted these people to like me and to accept me, so I just tried to act sad but not crazy.”

By the first anniversary of the accident, Gray was packing up her yellow bedroom. She took on odd jobs—at an exercise studio and then at an accounting firm—and lived with a roommate whom she rarely saw. In 1979, she moved to Southern California and returned to graduate school at U.C. Irvine. In Gray’s telling, her life improved with the elegance and the inevitability of a film dissolve. “It was a new start,” she said. “I felt like I was leaving the horribleness behind.” She loved her academic program, made friends, and went to the beach. But the accident remained with her. She said, “There was this voice: ‘You don’t deserve to feel happy. Look what happened last time you felt happy.’ I lived with a ghost, with this child inside me, speaking to me, not very kindly. But I never talked about it.”…

A tragic accident that was seemingly out of Gray’s conscious control. Or was it?

As you reflect on this story, what thoughts come to mind?

If this happened to you, how would you come to terms with it?

Should anyone objectively be (and feel) guilty for the outcome of this tragedy?

Could this event have been prevented?

The author of the New Yorker article raises these and other questions, juxtaposing the consequences with the impact on all parties.

This includes the notion that it was not beyond the boy’s control.

Be that as it may, the issue is so horrible and tragic that this question goes unaddressed.

ARE WE ALL VULNERABLE?

We live in a world where unanticipated events happen.

We are at the mercy of the moment.

Because we are human and capable of symbolic reasoning, we can transport ourselves into the past and/or the future using only our minds and imagination. This includes construing reality to fit our needs and desires.

We can create fantastic paradigms to assuage uncertainty, such as a belief in a superordinate being or a guardian angel, to subdue it…IT IS IN GOD’S HANDS or …IT IS GOD’S WILL FOR OUR OWN GOOD, or GOD WANTED THIS TO OCCUR BECAUSE THERE IS A SILVER LINING, and so on, then convince ourselves that this is true (the Boy’s Death in the previous story was ultimately “God’s Will”).

Still, our imagination doesn’t suspend unpredictability, and it’s easy to become entangled in cycles of fear and worry.

Like Maryann Gray, one minute carefree, the next uncertain, much of it beyond our control.

This is the challenge (and the benefit) of living. The only thing we are sure of is our mortality. At some point, your life (and mine) will end.

In the process, life is a “crapshoot.”

WHO DEVELOPED THE IDEA OF MORAL LUCK?

No one.

The idea of attributing meaning (beyond the reality of consequences) that occur outside of our control has been an intuitive feature of humanity since we developed symbolic thought and language.

This phenomenon has strengthened as we refined our imaginative reasoning skills.

What are “Imaginative Reasoning Skills?”

Imaginative Reasoning is the cognitive process of using imagination to solve problems, create new ideas, or understand complex situations by exploring possibilities beyond what is immediately apparent or logically clear.

If things just happened and we didn’t think beyond the present, moral luck would still exist, but we wouldn’t know it.

Animals experience moral luck events all the time, but they don’t realize it.

They live only in the present. No animal can imagine the future or dwell on the past. They may seem to behave this way, but it is instinctual, not symbolic or reflective of their true nature.

Imaginative Reasoning is the human door to the eternities.

There is almost nothing we cannot imagine. Our dreams are ongoing, whether we like it or not, a sign that imagination is driving the human psyche. As I write this blog, I am in active imaginative mode; otherwise, I wouldn’t know what to write next.

Creativity is a human extension of imagination. To create is to be “Godlike.”

We also create rules. Rules reign in our creative potential.

Why do we do this?

Because rules give us a sense of order and comfort, a structure to live by, where there are rules, there is “certainty.” When rules are absent, “uncertainty” is everywhere. Ambiguity is chaos and fear.

That’s why villains break the rules. The Devil is a rule-breaker par excellence; however, the Devil must have some rules; otherwise, the Devil wouldn’t exist.

We become afraid and scared, uncertain, when the rules are ambiguous or confusing.

THE POWER OF MORAL LUCK

In the Moral Luck example above, MaryAnn Gray says to herself, “You took a son from his mother, and your punishment is that you can never have your own child.”

This is Gray, reframing the 10-Commandment, “Thou shalt not kill.” To align with her situation. She then concludes that she killed the boy. She was somehow in control of the event. She does this, invoking the Control Principle described earlier on herself.

Gray is now, by her own imaginative doing, subject to moral judgment, and as the arbiter of judgment of her own life, evaluates herself as having broken one of the 10 Commandment Rules and must pay for her misdeed. The payment is her self-devised punishment, never having a child of her own.

What’s interesting about Gray’s imaginative process is that by reframing reality in this way and then following her self-created new reality, including generating her self-imposed punishment, Gray can alleviate some of her tortured feelings of guilt and shame that are exacerbated by ambiguity. Now, she can pay for this horrendous accident and set right in her mind what has been wronged.

This is an excellent example of how a person restructures reality to reinstate “Moral Luck,” thereby decreasing (or eliminating) uncertainty.

SUMMARY

In this entry, I introduced Moral Luck.

…situations where someone is judged morally (praised or blamed) for an action and/or its consequences, even though the person had limited or no control over a particular action associated with the result.

This idea is of “human” origin. Our faculties of imagination and creativity generated it to bring order to the world of “random events.”

Why do this?

The purpose of “Moral Luck” is to reduce life uncertainty and ensure that events, which are difficult to explain or understand (because they are random or happenstance), yet significantly impact us, leave us feeling psychologically unsettled.

We can employ imagination to create a sense of meaning or purpose, and then invoke our well-established human rules and order, which can calm us and settle a mind disturbed by the unexplainable, even if it means punishing ourselves (as in Gray’s situation).

Through the power of imagination, we can reconstrue our situation (in Gray’s case, making her the guilty party) and reestablish order. This is the extent that people will go to eliminate uncertainty, and why Moral Luck exists.

The only alternative is that of the True Believer who can subordinate randomness or chance to a “Higher Power.” Short of this, Moral Luck is what’s left to close the loose end loop of happenstance. Unless, of course, one faces reality as it is and decides to live with the uncertainty.