Mental Status

What is a Mental Status Examination?

What are tools psychologists use to evaluate client Mental State?

An essential tool for what I call primary functional health is the Mental Status Exam.

You’ve probably heard this term “Mental Status” before.

What is the difference between “Mental State” and “Mental Status”

The distinction is embedded in the second word. “State” versus “Status”.

Mental State defined: (Noun): A mental condition in which the qualities of a state are relatively constant even though the state itself may be dynamic. For example: “A manic state.”

Mental Status defined (Noun): from the American Psychological Association Dictionary: “the global assessment of an individual’s cognitive, affective, and behavioral state as revealed by a mental examination that covers such factors as general health, appearance, mood, speech, sociability, cooperativeness, facial expression, motor activity, mental activity, emotional state, trend of thought, sensory awareness, orientation, memory, information level, general intelligence level, abstraction and interpretation ability, and judgment.” I note that the APA does not explicitly define mental state.

It seems from these two definitions that the word “Status” has an additional feature of quantification: Note the words “…examination” and “…assessment.” The word “status” is defined as: position or rank in relation to others. Which is determined through quantification. Whereas the word, “state” is amorphous, defined as: a mode or state of being

When you think of Mental Status, What comes to your mind?

For me, “Mental Status” is a ubiquitous phrase in the mental health lingo. Originally it was simply an interview. Over time it evolved into what is known as the Mental Status Examination discrete tests or instruments that assess mental and cognitive abilities. I’ve administered hundreds of Mental Status Examinations. I’ve observed systematic errors made on these exams by persons with characteristic psychiatric diseases including schizophrenia, clinical depression, anxiety or dementia, and under conditions of delirium and drug intoxication where mental status is temporarily impaired.

Why is Mental Status Important?

Mental Status is a prerequisite to determining the status of a person’s psychological capacity, and to some extent, physical function. It would be difficult to determine what kind of mental health interventions a client will benefit from without, first, knowing the person’s mental status.

If you’re the client of a Psychiatrist, Psychologist, a Primary Care Provider MD, a Nurse, or a Social Worker, it is likely this medical or mental health professional at the time you were seen, recorded information (it might be a rating or a score) about your mental status: Intact or Impaired, Good or Poor, Functional or Dysfunctional. “How many fingers am I holding up?”

In my own practice, I record mental status for every client I see every time I see the client. This doesn’t mean I conduct a formal mental status examination every time I see a client, but I do judge whether the person’s mental status is intact or impaired or if it has changed since the last time I saw the client.

Defining Mental Status

Mental Status: A comprehensive description or statement of a client’s intellectual capacity, emotional state, and general mental health based on the provider’s observations and directed interview of the client. Mental Status includes assessment of mood, behavior, orientation, judgment, memory, problem-solving ability, and contact with reality.

This topic may be viewed by some as mundane, but assessing Mental Status is so pervasive and central to mental health care that it is important for providers and consumers of mental health services to know what Mental Status is and understand how Mental Status is applied in psychiatric diagnoses and in therapy, as well as its implications. Whether a client’s mental health is: 1. improving, 2. staying the same, or 3. getting worse over time.

I’ve treated hundreds of clients in inpatient and outpatient settings in different regions of the country and in the world who vary in their mental status. Sometimes mental status impairment can be permanent as in moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Sometimes mental status impairment is temporary as when a person is intoxicated with drugs or alcohol. Sometimes mental status can be impaired temporarily for physiological reasons such as in delirium (which is an acutely disturbed state of mind that occurs in fever, intoxication, and other disorders and is characterized by restlessness, illusions, and incoherence of thought and speech). There are times when Mental Status is psychopathological as in mental status impairment due to trauma (mental status can be impaired because of intrusive thoughts about a traumatic event, including nightmares and flashbacks) when there is no apparent physiological cause.

Expert mental health providers should be able to administer and diagnose mental status quickly and accurately. Sometimes a documented mental status issue needs to be followed up by more extensive neuropsychological examinations (which I will discuss in a later entry). This frequently occurs in persons with Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) where the impairment is not visually discernible and can only be observed and determined through the behavior of the individual.

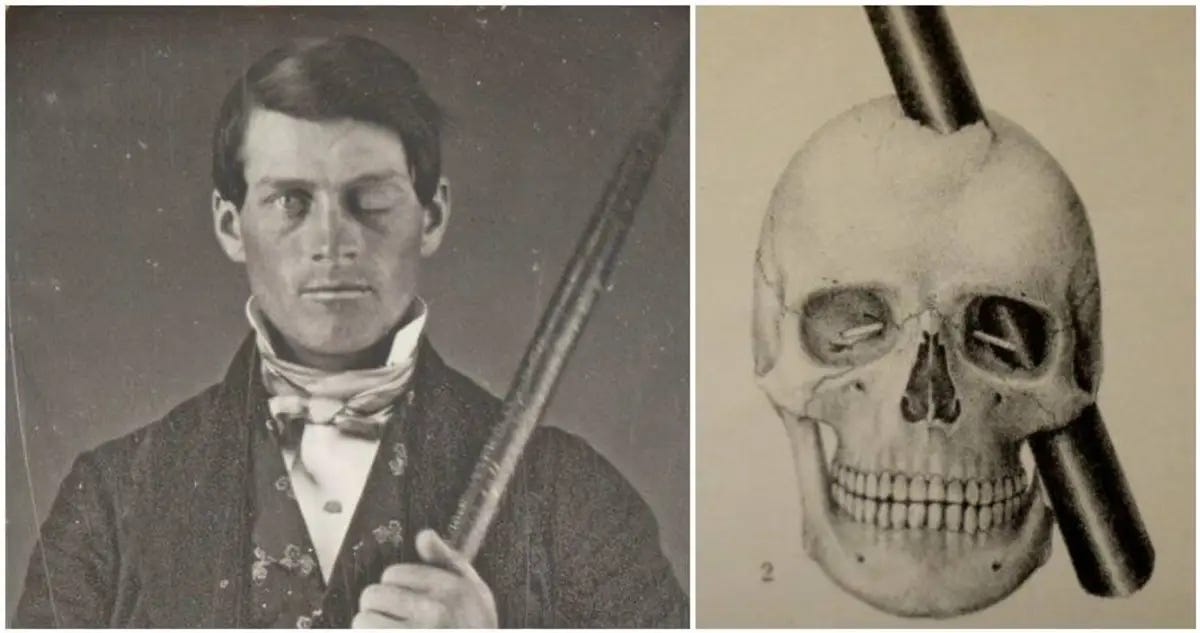

The famous story of Phineas Gauge comes to mind:

In brief, (Taken from the University of Akron Archives, Cummings Center for the History of Psychology where the physical documentation about Phineas Gage resides).

Phineas Gage was the foreman of a railway construction gang working on the Rutland and Burlington Rail Road near Cavendish, Vermont. On 13th. September 1848, an accidental explosion of a charge Gage had set blew his tamping iron through his head. The tamping iron was 3 feet 7 inches long and weighed 13 1/2 pounds. It was 1 1/4 inches in diameter at one end and tapered over a distance of about 1-foot to a diameter of 1/4 inch at the other. Like a missile, the tamping iron went in point first under his left cheek bone and completely out through the top of his head, landing about 25 to 30 yards behind him. Phineas was knocked over but may not have lost consciousness even though most of the front part of the left side of his brain was destroyed. Dr. John Martyn Harlow treated Gage with such success that 10 weeks later, Gage returned home to Lebanon, New Hampshire. Some months after the accident, probably around the middle of 1849, Phineas felt strong enough to resume work. But, because his personality had changed, the contractors who had employed him would not retain him. Before the accident he had been their most capable and efficient foreman who his co-workers described as a person with a well-balanced mind, and who was viewed as a shrewd smart businessman. He was now fitful, irreverent, and grossly profane, showing little deference for his fellows. He was also impatient and obstinate, yet capricious and vacillating, unable to settle on any plans. His friends said he was "No longer Gage."

When the brain is profoundly damaged, behavioral manifestation of that damage are common. The brain rests in a fluid in the skull, so damage can result when the skull is not penetrated. “Compression” damage is commonly known as Traumatic Brain Injury (or TBI). The Mental Status Exam is a key instrument in assessing the presence or absence of TBI damage. Refined neurological testing can tease out precisely what the damage is and where it occurs in the brain, but this is time-consuming and requires a professional with neuropsychological training.

Assessing Mental Status is challenging for the inexperienced clinician who can miss subtle signs of impairment and therefore not see issues in a client which then might preclude optimal treatment. Clinicians need training, experience, and understanding seeing, treating, and managing a variety of mental status conditions. Expert examiners of Mental Status can develop clear templates for understanding the connection between a mental status impairment and altered cognition/reasoning.

The Mental Status Examination

A Mental Status Examination might be viewed as a mental health provider’s version of the physical examination.

As a formal part of the larger psychiatric diagnostic interview, it was the Swiss physician, Adolf Meyer, who in 1918 published a rough outline of ideas to help him evaluate a patient’s “Mental Status”. These were originally transcribed into a free-narrative format to guide the provider in the passive observation of a client’s behavior.

In addition to observation, the outline suggested direct questions to assess the patient’s mental status at the time of the interview. Meyer’s outline became a zeitgeist for focusing on patient Mental Status as a precursor to treating mental illness.

Since then, as an assessment device, the Mental Status Examination, has been refined around questions related to localized brain functions and with standardized scoring based on population norms. Below are categories of a typical Mental Status Exam:

APPEARANCE

BEHAVIOR

SPEECH

MOOD AND AFFECT

THOUGHTS AND PERCEPTION

COGNITION

INSIGHT AND JUDGEMENT

These would seem, at first, easy to evaluate. Sometimes, they are. But there are many subtle nuances that a skilled clinician learns to identify.

APPEARANCE:

What a person looks like is a function of how the person self-cares. For clothing, not only what is worn, but how it is worn (a healthy person doesn’t wear a button-down shirt backwards, a person usually wears shoes to an interview). If a person has combed hair, is shaved, groomed and the person is prepared to be seen by others, this is a good sign. Good posture is a positive appearance factor. Smooth gait (a person's manner of walking) is a plus. Smelling of alcohol is suspicious. (Neglect in these areas is suspicious of impairment (e g., in Schizophrenia, personal neglect is called failure to thrive). I usually use the phrase: “Well dressed” or “Appropriately dressed” to note intact mental status in APPEARANCE.

BEHAVIOR

It is a positive sign to observe a client who is semi-relaxed, with a cooperative attitude who is open to questions, insightful and uses accurate language. Observing distractedness, an inability to focus attention on a topic, defensiveness, acting secretive - there could be many reasons for this kind of behavior. One reason is unstable mental status. In a first interview, unusual behavior can raise concern that the person might be hiding something (maybe, for example, for delusionary purposes). I interviewed a person, once, who was extremely secretive around me, getting up and checking the waiting room during the interview. It turned out the person thought I was an FBI Agent under the guise of a therapist. This is not a good sign for intact mental status. A client once asked me, “Dr., Why are there so many doors in your office? I asked him why he was concerned about this. He said, “Because, someone could be around the corner of one of these doors with a gun. If so, you (and I) are dead men. The list of behavior I attend to is long: eye contact (this could be cultural) or shifting eyes, gestures, facial expression, level of arousal at the interview. Behavior also includes subtle autonomic signs (a slight tremble of the hand could indicate Parkinson’s disease or abject but hidden fear).

SPEECH

When people see a psychologist for the first time, my experience is that although they have a concern, they generally want me to perceive them as OK. People usually present their “best” self to the clinician, so mental status issues might not easily be discerned, say, from appearance or behavior. I’ve conducted many Mental Status Examinations because a client, say a person with dementia, doesn’t want to go into an office with a white-coated doctor inspecting every aspect of their lives and their issues. Most people, for example, don’t want to be diagnosed with dementia, so they try to look and act as coherent as they can. A caregiver, on the other hand, is usually stressed out by behavioral problems of the care recipient. The caregiver sees this person every day. It is the caregiver who will sometimes give the most realistic (perhaps pessimistic) appraisal of the client’s functioning and mental state. In some cases, the client may NOT want the caregiver in the room when you administer a mental status exam. Speech, however, is hard to hide. For example. I showed one client a Coke can and asked him what this was. He said, “it’s an aluminum cylindrical thing, manufactured to hold a liquid, some kind of soda.” This client had a “confrontation naming impairment.” His expressive speech (also known as Broca’s area in the brain) was impaired for some reason even though his general intellect was intact. He knew what it was, but couldn’t say it.

MOOD AND AFFECT

It is noteworthy that in mental status, mood and affect are both related to emotion, but they are NOT the same thing. Mood refers to the more sustained emotional makeup of a client’s personality. Affect is the client’s immediate expression of emotion. Clients might display a range of affect that may be described as broad, restricted, labile, or flat. Affect is inappropriate when there is no relationship between what the client is describing and the emotion the client is showing at the same time (e.g., laughing when relating the recent death of a loved one). Both affect and mood can be described as dysphoric (depression, anxiety, guilt), euthymic (sad, normal), or euphoric (implying a pathologically elevated sense of well-being).

THOUGHTS AND PERCEPTIONS

This is a challenging feature of Mental Status. Thoughts emerge from speech. The clinician infers thoughts of a client by what the client says. Is what the client saying logical? Does it make sense? Sometimes thoughts are blocked. A person will start to express a thought, then stop. What causes this disruption of speech flow? Is it speech or is it something related to how a person thinks or feels. These are difficult aspects of thought to disentangle. The ability to mentally process information correctly is part of the definition of normality. It is useful to break down “thought” into two elements: 1. process and 2. content. Process=how a person describes a thought - logically, rationally, or incomprehensibly. Content refers to what a person is actually saying or the content of ideas, beliefs. Impaired content could be due to obsessions or preoccupations.

Perception is different than thought. Perception = awareness. We are aware by mere fact that we process input from reality that we sense. Perception is “processed sensation.” Abnormal perceptual experiences are part of the clinical picture of most mental disorders. What we experience by way of our senses can be altered by our own mental processing of a sensation. Hallucination, for example, are perceptions without an external stimulus. Hallucination defined is: An experience involving the apparent perception of something not present. I use hallucination here because drugs, for example, Psilocybin, have known pharmacological properties that alter the processing of visual and auditory sensations. Such a drug, or hallucinogen, when taken, creates a predictable temporary disruption in mental status. It could also be that certain features of our internal brain metabolism can produce the same alterations in sensation, only there is no drug explanation. EXAMPLE: When a person is dehydrated, this can alter mental processing capability. A dehydrated person will frequently describe hallucinations.

I recall interviewing an older female 80+ years, very thin, fragile. She complained of headaches and confusion. I touched the top of her hand, dry and cool. She said she lacked energy. She had spent the day with her caregiver, not stopping due to multiple medical appointments. I was the last person on her appointment list. She had all of the manifestations of dehydration. She reported feeling dizzy when she walked, her eyes seemed sunken in her head, lips were cracked. We started the interview, mostly it was a conversation. The client was nearly incoherent, not making sense. I suggested we take a break. During the break, I gave her a small bottle of water, I indicated that she should sip the water continuously. I had a similar bottle and I asked her to sip when I sipped. Soon, she finished it and asked for a second bottle. As the interview progressed, her mind became clearer, she started answering questions better, seemed more in touch with me as the interviewer. She also remarked that she was feeling significantly better. At the end, I reasoned that she was less demented and more dehydrated. She remarked that the interview was almost a miracle. She said, “Dr., just talking to you today made me feel better, I really want to come back for more visits.” Still, she (nor her caregiver) had connected her dehydration to her cognitive and physical symptoms. A lesson learned that multiple factors, including dehydration, can impact Mental Status.

COGNITION

FORMALIZED MENTAL STATUS EXAMINATIONS ARE TESTS OF COGNITION

Thoughts and cognitions are not the same thing. In an enormously influential book written in 1958 (The Human Condition), the philosopher Hannah Arendt attempted to distinguish between thought and cognition. I quote her below:

“Thought and cognition are not the same. Thought, the source of art works, is manifest without transformation or transfiguration in all great philosophy, whereas the chief manifestation of the cognitive processes, by which we acquire and store up knowledge, is the sciences. Cognition always pursues a definite aim, which can be set by practical considerations as well as by “idle curiosity”; but once this aim is reached, the cognitive process has come to an end. Thought, on the contrary, has neither an end nor an aim outside itself, and it does not even produce results.”

So, cognition is “thinking skills.” Thinking Skills are the mental processes we use to achieve things like: solve problems, make decisions, ask questions, make plans, pass judgements, organize information and create new ideas within a paradigm of rules. Cognition is Science, a kind of thought, usually systematic, with a goal in mind, that is fixed on a problem until the problem is solved or the solution is fabricated.

Thoughts are unmolested ideas and concepts that have no purpose or source…Art emerges from this framework. Thought never stops.

It is more straight-forward to measure thinking skills because cognition focuses on how people approach and solve concrete problems. When these skills break-down (or perhaps they never were acquired), this is an indication of Mental Status Impairment. To assess this, Psychologists have developed focused tests of cognition.

These are published as mental status exams. For example, The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is a widely used screening assessment for detecting COGNITIVE impairment (Important: Cognition is just one component of mental status). It was created in 1996 by Ziad Nasreddine in Montreal, Quebec and has been adopted in other settings world-wide. It is easy to access by applying for permission to use the copyrighted version: https://www.mocatest.org/permission/

I’m copying the scoring form for the MoCA below:

The MoCA is straight-forward and can be administered with some training and practice. I’m copying the instructions below. Instructions are not intended for you to learn how to administer the test, instead, to appreciate the kinds of questions that are used to evaluate the specific domain of cognitive function.

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)

Administration and Scoring Instructions

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was designed as a rapid screening instrument for mild cognitive dysfunction. It assesses different cognitive domains: a: attention and concentration, b: executive functions, c: memory, d: language, e: visuoconstructional skills, f: conceptual thinking, g: calculations, and h: orientation. Time to administer the MoCA is approximately 10 minutes. Total score is 30 points; a score of 26 or above is considered normal cognition.

1. Alternating Trail Making:

Administration: The examiner instructs subject: "Please draw a line, going from a number to a letter in ascending order. Begin here [point to (1)] and draw a line from 1 then to A then to 2 and so on. End here [point to (E)]."

Scoring: Allocate one point if subject draws pattern: 1 −A- 2- B- 3- C- 4- D- 5- E, without drawing any lines that cross. Any error that is not immediately self-corrected earns a score of 0.

2. Visuoconstructional Skills (Cube):

Administration: The examiner gives the following instructions, pointing to the cube: “Copy this drawing as accurately as you can, in the space below”.

Scoring: One point is allocated for a correctly executed drawing.

Drawing must be three-dimensional

All lines are drawn

No line is added

Lines are relatively parallel and their length is similar (rectangular prisms are accepted)

A point is not assigned if any of the above-criteria are not met.

3. Visuoconstructional Skills (Clock):

Administration: Indicate the right third of the space and give the following instructions: “Draw a clock. Put in all the numbers and set the time to 10 past 11”.

Scoring: One point is allocated for each of the following three criteria:

Contour (1 pt.): the clock face must be a circle with only minor distortion acceptable (e.g., slight imperfection on closing the circle);

Numbers (1 pt.): all clock numbers must be present with no additional numbers; numbers must be in the correct order and placed in the approximate quadrants on the clock face; Roman numerals are acceptable; numbers can be placed outside the circle contour;

Hands (1 pt.): there must be two hands jointly indicating the correct time; the hour hand must be clearly shorter than the minute hand; hands must be centered within the clock face with their junction close to the clock center.

A point is not assigned for a given element if any of the above-criteria are not met.

4. Naming: Administration: Beginning on the left, point to each figure and say: “Tell me the name of this animal”. Scoring: One point each is given for the following responses: (1) lion (2) rhinoceros or rhino (3) camel or dromedary.

5. Memory: Administration: The examiner reads a list of 5 words at a rate of one per second, giving the following instructions: “This is a memory test. I am going to read a list of words that you will have to remember now and later on. Listen carefully. When I am through, tell me as many words as you can remember. It doesn’t matter in what order you say them”. Mark a check in the allocated space for each word the subject produces on this first trial. When the subject indicates that (s)he has finished (has recalled all words), or can recall no more words, read the list a second time with the following instructions: “I am going to read the same list for a second time. Try to remember and tell me as many words as you can, including words you said the first time.” Put a check in the allocated space for each word the subject recalls after the second trial. At the end of the second trial, inform the subject that (s)he will be asked to recall these words again by saying, “I will ask you to recall those words again at the end of the test.” Scoring: No points are given for Trials One and Two.

6. Attention: Forward Digit Span: Administration: Give the following instruction: “I am going to say some numbers and when I am through, repeat them to me exactly as I said them”. Read the five number sequence at a rate of one digit per second. Backward Digit Span: Administration: Give the following instruction: “Now I am going to say some more numbers, but when I am through you must repeat them to me in the backwards order.” Read the three number sequence at a rate of one digit per second. Scoring: Allocate one point for each sequence correctly repeated, (N.B.: the correct response for the backwards trial is 2-4-7).

Vigilance: Administration: The examiner reads the list of letters at a rate of one per second, after giving the following instruction: “I am going to read a sequence of letters. Every time I say the letter A, tap your hand once. If I say a different letter, do not tap your hand”. Scoring: Give one point if there is zero to one errors (an error is a tap on a wrong letter or a failure to tap on letter A).

Serial 7s: Administration: The examiner gives the following instruction: “Now, I will ask you to count by subtracting seven from 100, and then, keep subtracting seven from your answer until I tell you to stop.” Give this instruction twice if necessary. Scoring: This item is scored out of 3 points. Give no (0) points for no correct subtractions, 1 point for one correction subtraction, 2 points for two-to-three correct subtractions, and 3 points if the participant successfully makes four or five correct subtractions. Count each correct subtraction of 7 beginning at 100. Each subtraction is evaluated independently; that is, if the participant responds with an incorrect number but continues to correctly subtract 7 from it, give a point for each correct subtraction. For example, a participant may respond “92 – 85 – 78 – 71 – 64” where the “92” is incorrect, but all subsequent numbers are subtracted correctly. This is one error and the item would be given a score of 3.

7. Sentence repetition: Administration: The examiner gives the following instructions: “I am going to read you a sentence. Repeat it after me, exactly as I say it [pause]: I only know that John is the one to help today.” Following the response, say: “Now I am going to read you another sentence. Repeat it after me, exactly as I say it [pause]: The cat always hid under the couch when dogs were in the room.” Scoring: Allocate 1 point for each sentence correctly repeated. Repetition must be exact. Be alert for errors that are omissions (e.g., omitting "only", "always") and substitutions/additions (e.g., "John is the one who helped today;" substituting "hides" for "hid", altering plurals, etc.).

8. Verbal fluency: Administration: The examiner gives the following instruction: “Tell me as many words as you can think of that begin with a certain letter of the alphabet that I will tell you in a moment. You can say any kind of word you want, except for proper nouns (like Bob or Boston), numbers, or words that begin with the same sound but have a different suffix, for example, love, lover, loving. I will tell you to stop after one minute. Are you ready? [Pause] Now, tell me as many words as you can think of that begin with the letter F. [time for 60 sec]. Stop.” Scoring: Allocate one point if the subject generates 11 words or more in 60 sec.

9. Abstraction: Administration: The examiner asks the subject to explain what each pair of words has in common, starting with the example: “Tell me how an orange and a banana are alike”. If the subject answers in a concrete manner, then say only one additional time: “Tell me another way in which those items are alike”. If the subject does not give the appropriate response (fruit), say, “Yes, and they are also both fruit.” Do not give any additional instructions or clarification. After the practice trial, say: “Now, tell me how a train and a bicycle are alike”. Following the response, administer the second trial, saying: “Now tell me how a ruler and a watch are alike”. Do not give any additional instructions or prompts.

Scoring: Only the last two item pairs are scored. Give 1 point to each item pair correctly answered. The following responses are acceptable: Train-bicycle = means of transportation, means of travelling, you take trips in both; Ruler-watch = measuring instruments, used to measure. The following responses are not acceptable: Train-bicycle = they have wheels; Ruler-watch = they have numbers.

10. Delayed recall: Administration: The examiner gives the following instruction: “I read some words to you earlier, which I asked you to remember. Tell me as many of those words as you can remember.”

Make a check mark ( √ ) for each of the words correctly recalled spontaneously without any cues, in the allocated space. Scoring: Allocate 1 point for each word recalled freely without any cues.

Optional: Following the delayed free recall trial, prompt the subject with the semantic category cue provided below for any word not recalled. Make a check mark ( √ ) in the allocated space if the subject remembered the word with the help of a category or multiple-choice cue.

Prompt all non-recalled words in this manner. If the subject does not recall the word after the category cue, give him/her a multiple choice trial, using the following example instruction, “Which of the following words do you think it was, NOSE, FACE, or HAND?” Use the following category and/or multiple-choice cues for each word, when appropriate: FACE: category cue: part of the body multiple choice: nose, face, hand VELVET: category cue: type of fabric multiple choice: denim, cotton, velvet CHURCH: category cue: type of building multiple choice: church, school, hospital DAISY: category cue: type of flower multiple choice: rose, daisy, tulip RED: category cue: a color multiple choice: red, blue, green Scoring:

No points are allocated for words recalled with a cue. A cue is used for clinical information purposes only and can give the test interpreter additional information about the type of memory disorder. For memory deficits due to retrieval failures, performance can be improved with a cue. For memory deficits due to encoding failures, performance does not improve with a cue.

11. Orientation: Administration: The examiner gives the following instructions: “Tell me the date today”. If the subject does not give a complete answer, then prompt accordingly by saying: “Tell me the [year, month, exact date, and day of the week].” Then say: “Now, tell me the name of this place, and which city it is in.” Scoring: Give one point for each item correctly answered. The subject must tell the exact date and the exact place (name of hospital, clinic, office). No points are allocated if subject makes an error of one day for the day and date.

TOTAL SCORE: Sum all sub-scores listed on the right-hand side. Add one point for an individual who has 12 years or fewer of formal education, for a possible maximum of 30 points. A final total score of 26 and above is considered normal.

INSIGHT AND JUDGEMENT

Insight is the client’s awareness and understanding of his or her own illness. When evaluating a client’s insight, Does the client understand how a given illness, mental, or physical disorder impacts his or her life, relationship with others, and willingness to change.

SUMMARY

Implications: Clinical Judgement and Risk Assessment

A Mental Status Examination evaluates: “DECISIONAL CAPACITY.” Does the examinee have sufficient decisional capacity to determine (along with the doctor) what is in the examinee’s best interest given the specific situation that the examinee finds him or herself in?

When you see a Medical or Mental Health Provider, it can be maddening when the professional presents you with options and asks you what “you” think is the best way to move forward with your condition. One might, in response, say, “Doctor, you are the expert, the person with all the knowledge, you simply tell me what needs to be done and I will do it.”

This statement is seductive (maybe too easy at one level) because it puts all the responsibility for understanding your condition and its treatment on the Doctor. In some cases, say, if your decisional capacity is sufficiently impaired, this might be the default option. But, in most cases, if at all possible, the Doctor wants your own personal views about your illness. Why? Because Western culture favors client autonomy—an individual client’s right to self determination—over the beneficent protection offered by others. In our Western world, adults are believed, by default, to be “good enough” to make their own decisions—for better or worse—even though someone else might be a better decision-maker for them from a purely objective, academic or analytic point of view.

Restricting autonomy requires a clear and convincing assessment that a client’s impaired decision capacity will result in unintended, irreparable harm.

Consider the following case example: (abstracted from a public domain journal article)

A 54-year-old woman with diabetes and schizophrenia is hospitalized with unstable angina, bilateral heel ulcers, urinary retention caused by an acute urinary tract infection and anemia caused by a combination of gastritis and chronic renal failure. One year ago, she was hospitalized with diabetic ketoacidosis after reporting that “voices” told her to stop taking her insulin. Currently, she is improving but requires a urinary catheter and must keep her legs elevated at rest. She says she is now able to take care of herself and wants to return home. Does this patient have the capacity to make this decision?

Can a professional determine if another person is capable of making decisions for himself or herself that could substantially impact this person’s health?

The Mental Status Exam offers only a narrow point of view on decisional-capacity because the focus is on whether a person can negotiate a discrete set of functional behaviors and if a person can distinguish, say, external reality from one’s own, perhaps, faulty beliefs and self-perceptions.

While it is true that if you believe that the Government is conspiring against you, you will probably make different decisions about your future than if you feel that you are not in imminent danger. Similarly, if your vision or your perception is impaired for some reason, you probably shouldn’t drive a car even if you think that you can drive a car without difficulty, just a little more concentration is all that is needed.

A Mental Status Exam can provide standardized information on these important, but narrow, capabilities versus what you can do well or your ability to compensate for deficits. In this case, a neutral Mental Status Exam score, no errors, would be judged as an affirming outcome. The Mental Status Exam is what I call a gatekeeper measurement.

I recall 15 years ago seeing an 83 year old female caregiver who was caring for an 84 year old male spouse with Dementia (his name was Unk or short for Uncle). The caregiver said, I must yell at Unk every day because he can’t hear. He is functionally deaf. I conducted a mental status exam. I asked Unk to close his eyes. Unk sat there and looked at me, eye-wide-open. The caregiver said, “he can’t hear you.” So, she proceeded to yell at Unk at nearly a scream, where-upon he blinked his eyes. She then said, “See, Doctor, you just need to speak up and say things clearly.” I then took a large piece of paper and wrote the words in large block letters, UNK, CLOSE YOUR EYES. I showed it to Unk. he looked at it for a long time, his eyes never closed. I pointed to the sign, pointed to my eyes and closed my eyes. Then, I opened my eyes, pointed to the sign, then pointed to him. He did follow my finger, but he continued to stare at me, but never did he close his eyes. From this, I concluded that it was likely that Unk had also lost the ability to read or take directions, perhaps understand anything that was said to him. Still, the caregiver, who watched the entire process, said, after a time, “Yes, but he still can’t hear.”

We really never found out if “Unk” was able to hear or not, but there was, for sure, something more than just hearing that was preventing him from understanding others. Unfortunately, that’s as far as a Mental Status Exam could go in this case.

President Donald Trump on Wednesday, May 23, 2019 (Politico https://www.politico.com/story/2019/05/23/trump-stable-genius-1342655) defended his mental fitness to hold office and described the Mental Status Exam he allegedly took assessing his cognitive capabilities, claiming the doctors administering it were amazed by his ability to recall a simple string of words.

Trump said, “It was 30 or 35 questions. The first questions are very easy. The last questions are much more difficult. Like a memory question,” Trump continued. “It’s like, you’ll go, ‘Person, woman, man, camera, TV.’ So they say, ‘Could you repeat that?’ So I said, ‘Yeah.’ So it’s, ‘Person, woman, man, camera, TV.’ OK, that’s very good. If you get it in order, you get extra points.”

Then, “10 minutes, 15, 20 minutes later” in the cognitive exam, “they say, ‘Remember the first question?’ Not the first, but the tenth question. ‘Give us that again. Can you do that again?’ And you go, ‘Person, woman, man, camera, TV,’” Trump recounted.

President Trump is describing a Mental Status Examination (The MoCA that I described above). What can we learn from this. Trump was, at the time of the MSE, functionally intact, but not much more can be known. Trump asserts, “I’m an extremely stable genius. OK?” But, this assertion is far beyond what one could conclude from a Mental Status Exam. I present this example to underscore that it is easy to misjudge the capability of a Mental Status Exam to evaluate a person’s broader capacities and certainly it cannot assess strengths or maximum capabilities, nor is it a measure of intelligence by any stretch of the imagination. Too bad because cognitive strength and flexibility can be leveraged by an individual to compensate for some mental status deficits, but not all. Unfortunately, this cannot be ascertained from the Mental Status Exam itself. Other instruments and interview questions are required for a more refined understanding of a person’s mental capabilities, say, under stress or at maximal capacity.

If a person has mental status issues, then there are likely other larger problems looming in the background. This is why follow-up neuropsychological testing is always recommended in these cases.

For this reason, the full range of one’s functional status should NOT be solely based on a Mental Status Examination. It is a guide, not a determinant, of whether a person can make decisions for him or herself. This is where clinical judgement and professional wisdom enter the picture. These two latter terms I could write multiple entries about and will do so in future entries.

What about the Case Example?

In the Case Example above, here was the eventual outcome:

The 54-year-old woman with schizophrenia and multiple medical problems reported that she was not now hearing voices nor was she exhibiting any other psychotic symptoms. She had been very stable on her psychiatric medications for several months. The patient understood her medical situation, appreciated the consequences of care options, analyzed logically the information she was given and was able to express a clear choice. She was judged to have capacity. After learning self-catheterization, demonstrating knowledge of her medication regimen and agreeing to home health nursing care, she returned home and returned for follow-up visits as directed.

Ending This Entry for Now (9/3/2022)