Dr., I need help!

A client: “Bill,”

asked.

WHO will help me?

I wasn’t sure how to answer.

Bill was sitting in my office.

I was there to help.

But what kind of help did Bill need (or want)?

Bill was describing his personal dilemma and

From my POV, Bill was asking for advice.

Realizing that “he - Bill” was at a pivotal point in his life,

He wanted to know:

Should he act? 1. This way or 2. That way

From Bill’s POV, my help was advice.

Would it “help” Bill to give him what he’s asking for, advice?

When was the last time that you “REALLY” needed someone’s help?

Perhaps you needed help because you believed you could not continue without it.

Maybe you got the help you needed.

Maybe NOT.

Young children learn “help” before almost any other word.

As we age, the meaning of “Help” evolves.

Asking for help in adulthood is embedded in social conditions and prohibitions (e.g., “pull yourself up by your bootstraps,” “God only helps those who help themselves,” or “No freeloaders on this train”).

Should we EVER ask someone for help? even God (note above admonition)?

If so, when, how, from Whom, and where?

THEN, there is the other side of “help,”

Giving help.

We decide when, how much, with what, and under which circumstances we help others.

Are you willing to help? If so, with what? How much? And to whom?

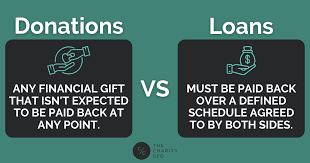

When you lend money, are you doing so to help?

Or

Is there an agenda?

Maybe you are helping yourself if you demand “interest” on the loan?

Is loaning money to someone with interest helpful?

Or is it something else?

Some see me as a “professional helper," a licensed psychotherapist.

I charge a fee for every therapy session, so there is an exchange of dollars for services provided.

Is this a form of helping?

What is Helping?

Help is defined as:

Help (Merriam-Webster dictionary) 1: to give assistance or support to (someone): to provide (someone) with something useful or necessary in achieving an end. (Can you help me get this jar open?)

The American Psychological Association Dictionary does not define “help” per se.

It describes Helping (as a noun): a type of prosocial behavior in which one or more individuals act to improve the status or well-being of one or more others. Although helping behavior is typically in response to a small request that involves little individual risk, all helping behavior incurs some cost to the individual providing it.

The definitions indicate that.

Help (or helping) is:

Assistance.

Necessary to achieve an end (for the receiver of the help).

A prosocial behavior.

Risky (or costly) to the person helping (what about to the person receiving the help?).

GIVING HELP

Is to assist another.

Assisting another in a helping role has assumptions.

A person, animal, thing, or object needs help.

You have something (time, money, expertise, etc.) that you can give.

That this “something” is worthwhile (or valued) as “helpful” by the recipient.

You are willing (or want) to help.

(If you offer a service against the receiver’s will, is this help?)

You help when there is a “need.”

Is helping without a need, Help?

This need may manifest as a request.

You may decide to help when you have no request, but only a need.

Your perceived helpfulness depends mainly on the recipient.

Providing help means sharing your resources, donating your time, effort, and expertise, or collaborating with others to achieve a common goal of assisting another.

Lots of people NEED help.

Many people make requests for assistance.

How/* do you determine when, how much, where, or to whom you will help?

I recall an experience while living in New Jersey. I was at a conference and a few of us went for lunch. On the return, we walked through a large parking lot. One of my colleagues said, “Do you hear that?” I listened and sure enough, I heard a faint sound of someone crying for help. It emanated from somewhere in the lot, empty of people, full of cars.

As a group of three, we searched for the sound, which we found after 20 minutes of walking between cars.

It turned out to be the voice of an older, somewhat frail woman who had fallen under her car, and the vehicle’s tire had rolled over the top of her arm.

Her cell phone was still in the driver’s seat, and the driver’s side door was open. The woman was quietly sobbing in a state of blind resignation. She, of course, brightened up when she heard our voices and pleaded with us to get this car off her arm.

I carefully looked into the driver’s seat and I noticed the car was set to neutral, with keys in the ignition. We finally reasoned that pushing the car forward by hand, freeing the woman, jumping into the car, applying the brakes, then pulling her out from underneath, starting the vehicle, and putting it in park would solve the issue.

We did this quickly. The woman was in shock, white, shaking, and delirious. She said she had been in this position for hours, calling and calling, but no one came.

It was hard to know how she got into this state, but her arm seemed okay. She called her daughter, and the daughter arrived quickly; soon, they were gone. The woman wanted to pay us, but it was incomprehensible to us to accept anything like that. After all, we had already been paid with the good feeling of rescuing someone in true distress.

This story highlights several keys of helping others.

Availability - Being at the right place at the right time is frequently not the result of planning, but chance. When the opportunity arises, being prepared and ready is crucial.

Willingness is critical, especially in cultivating a genuine desire to help when there is a need.

Acting when needed - We could have walked on back to our conference, not attending to the distress call. Perhaps others did; I don’t know. But I do know that no one was there to help and discern when and how to act. To “act” is an obvious, but critical step in “other” helping.

The self-help literature is filled with ideas on this topic.

I’ve been asked many times about helping others.

What is the answer?

The answer depends on YOU and your POV.

When you genuinely help another, you may experience a new paradigm, or a comprehensive shift in your perspective (POV).

Think about Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol.

For Scrooge, there is a before and after image: Scrooge as “miser, unhelpful” then as “giver, helpful.”

Does Scrooge feel differently “inside” depending on his “helping” disposition?

What influenced Scrooge to change his Point of View?

Was it an expressed or unexpressed need?

Was there no apparent need, rather something inside of Scrooge that changed his POV? (THINK ABOUT IT).

Do you think the need (if it was there) was simply a background factor?

Would Scrooge have changed his Point of View without awareness of another’s need, but as a consequence of passing time, leaving all things unchanged?

Was Scrooge’s experience that of evaluating himself or the person in need?

What does engaging in a generous act feel like?

Does “helping” always create an internal paradigm shift for those who help?

Is this desire for a “good” internal feeling why people decide to “help”?

OR

Is it simply a consequence of the helping act?

Or just a helping thought? (If you only think about helping, will you feel better?)

To give help and genuinely expect nothing in return, this is called:

ALTRUISM.

Altruism is defined (Merriam-Webster) as: 1: unselfish regard for or devotion to the welfare of others, and 2. behavior by an animal that is not beneficial to or may be harmful to itself but that benefits others of its species.

The American Psychological Association Dictionary defines Altruism as: n. an apparently unselfish behavior that benefits others at some cost to the individual. In humans, it covers a wide range of behaviors, including volunteerism and martyrdom, but the degree to which such behaviors are legitimate without egoistic motivation is subject to debate. In animal behavior, it is difficult to understand how altruism could evolve in a species since natural selection operates on individuals. However, organisms displaying altruism can benefit if they help their relatives or if an altruistic act is subsequently reciprocated.

These definitions ARE DIFFERENT:

Mer-W is unequivocal that altruism is “unselfish,” whereas the APA definition hedges (“apparently unselfish”).

Mer-W states altruism is NOT harmful to the giver, but the APA definition indicates that there may be harm to the giver (as in the case of martyrdom).

APA states that there is always “some cost” to the giver.

The APA definition states that altruism (in animals) may have a direct reciprocal benefit for the giver. This “benefit” aligns with an evolutionary theory of natural selection but does not align with the Me-W dictionary definition.

The APA definition implies that animal altruism is self-oriented, which is contrary to the Me-W definition.

Taken together, these are not the definitive description of helping.

An act of “philanthropy” is supposed to be altruistic. But is “philanthropy” really without reciprocity?

You give to a charity you value. Why do you value that charity? It is because the charity does something you want.

In this instance, you are NOT giving money or time freely. You are giving money for a reason (or your agenda).

Is this true philanthropy?

Is giving to further a purpose you want, desire, or support

PHILANTHROPY?

A person once said to me,” Dr. Hill, I am an active member of the LDS (Mormon) Church. I tithe 10% of my income. Why do I do this? I am reassured that God will help me spiritually and financially. I will never be “without” as long as I tithe.

“When I tithe, this allows God to help others.”

Then he said, “Tithing is God’s Commandment?”

Leviticus 27:30: “A tithe of everything from the land, whether grain from the soil or fruit from the trees, belongs to the Lord; it is holy to the Lord.”

2 Chronicles 31:5: “As soon as the order went out, the Israelites generously gave the first fruits of their grain, new wine, olive oil and honey and all that the fields produced. They brought a great amount, a tithe of everything.

Is this person (or family ) giving money to a religious organization without egotistic motives?

Is tithing behavior “altruistic?” “Is it philanthropy?” “Is it helping?” OR Is it something else?

I raise these questions to underscore that helping is not a simple idea or action.

Helping is rooted in human psychology, social, as well as religious, rules, values, and prohibitions, many of which we follow without much thought.

RECEIVING HELP

Receiving help should be straightforward, but it is not.

QUESTION

Under what conditions would you welcome help from another?

Scenario #1: Paying the Bill:

John’s family invites Steve’s family to dinner.

They go to a semi-nice restaurant.

Steve’s family is used to nice restaurants because Steve’s income exceeds John’s. At the end of the meal, John says, “Hey, I’ve had a great time.

Mary and I want to help you by paying the bill.

How does Steve feel?

Steve is glad John is helping him out because the bill is quite large, and now Steve can use his substantial money for other things. So, Steve thanks John, and they leave.

Steve starts worrying about John, whom he presumes can’t afford such a large restaurant bill. Steve thinks that John shouldn’t feel the need to give help; instead, John needs help in this situation because Steve is wealthier than John. Steve accepts John’s offer but feels guilty and says, “John, are you sure you can afford this bill? At least let me pay the tip.”

Steve resists John’s offer and says, John, hey, I know you’d like to help me, but I don’t need your help, and this is a lot of money. John, I know you aren’t wealthy, and I’ve plenty of money, so I don’t need your help. How about I pay the bill, and you pay it next time?

Steve says, John, I know you want to help, but paying the whole bill is too much help. Let’s split the bill and call it good.

HOW DOES JOHN FEEL UNDER EACH OF THESE CONDITIONS? AND WHY?

Scenario #2: A homeless person asks for money:

You are walking downtown. Someone who looks like a homeless person approaches you and asks for money.

You stop, reach into your wallet, purse, or handbag, then realize you have only a $20.00 bill, no change, and no smaller bills.

What do you do?

You give the $20.00 bill to the person.

You tell the person to wait and that you will make a change for the $20.00 bill. Once you have made the change, you come back and provide the amount you wanted to provide.

You look into your wallet and see the $20.00 bill, and say, 'Sir/madam, I’d like to give you something today, but I don’t have any money on me.' (In fact, you have a $20.00 bill.) 'I’m so sorry. '

You don’t stop. You ignore the person.

You stop and tell the person, “I hope you can get help; many homeless shelters nearby can provide you with food and meet your needs.” I suggest you find one of these.”

You ask if the person can make change for a $20.00 bill, and then you will give the person $1.00 of the $20.00 amount after the homeless person has made change for you and given you the smaller bills (if the person can make change, you proceed; if not, you walk away).

These situations highlight the numerous unwritten social rules internalized into more personal and individualized mental guidelines for determining when and to whom you will offer monetary assistance.

Note: These options contain many mixed messages due to conflicting values, prohibition, and shared social sense.

The decision to give money to a homeless person is classic.

HOW DO YOU FEEL ABOUT YOURSELF UNDER EACH OF THESE SCENARIOS AND WHY?

“Should I give to this destitute person asking me, directly, for help?”

or

Should I defer to a social system?

“Am I perpetuating the larger homelessness problem by giving this way?”

or

“Am I helping an individual in distress?”

OR

“Am I being duped by a clever con-artist posing as a needy homeless person?”

Who Can Know?

THE PARABLE OF THE GOOD SAMARITAN

The parable of the Good Samaritan in the Bible emphasizes helping and is held by many as a “gold standard” for charitable action. (Luke 10 29-30). It starts like this:

29 But he wanted to justify himself, so he asked Jesus, “And who is my neighbor?”

In reply, Jesus said:

‘30A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, when he was attacked by robbers. They stripped him of his clothes, beat him and went away, leaving him half dead. 31 A priest happened to be going down the same road, and when he saw the man, he passed by on the other side. 32 So too, a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side. 33 But a Samaritan, as he traveled, came where the man was; and when he saw him, he took pity on him. 34 He went to him and bandaged his wounds, pouring on oil and wine. Then he put the man on his own donkey, brought him to an inn and took care of him. 35 The next day, he took out two denarii and gave them to the innkeeper. ‘Look after him,’ he said, ‘and when I return, I will reimburse you for any extra expense you may have.’36 “Which of these three do you think was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of robbers?”37 The expert in the law replied, “The one who had mercy on him. ”Jesus told him, “Go and do likewise.”

Samaritan: The Samaritans lived in Israel following the Assyrian conquest and were known in Jesus’ time for their hostility towards the Jews. Jesus likely chose “Samaritan” to eliminate positive bias.

Denarii: Two denarii is two days’ worth of wages, indicating generosity.

The story describes generosity through a helping act to someone in distress.

Jesus answers the lawyer’s question with an implied response - act accordingly.

The story speaks to the three features of maturity: 1. Awareness, 2. Understanding, and 3. Intention. I have described these “states of being” elsewhere. The Samaritan applies them. Awareness of an unusual event that placed another in an unfortunate situation (through no fault of of the person’s own), understanding that the person was in need, so the Samaritan acted generously toward someone who the Samaritan in most other circumstances would disagree with, and finally, the Samaritan’s general intention to “help others in need.” Although not stated, this intention is discerning genuine from fabricated need, for example (as in the con artist posing as a homeless person).

WHAT IS MY HELPING DISPOSITION

I conclude this blog entry by sharing an instrument developed by the Fetzer Institute to measure one’s helping disposition.

HELPING ATTITUDES SCALE (HAS)

INSTRUCTIONS: “This instrument measures your feelings, beliefs, and behaviors concerning your interactions with others. It is not a test, so there are no right or wrong answers. Please answer the questions as honestly as possible. Using the scale below, indicate your level of agreement or disagreement in the space next to each statement.”

Helping others is usually a waste of time.

1=Strongly Agree

2=Agree

3=Undecided

4=Disagree

5=Strongly Disagree

When given the opportunity, I enjoy aiding others who are in need.

1=Strongly Disagree

2=Disagree

3=Undecided

4=Agree

5=Strongly Agree

If possible, I would return lost money to the rightful owner.

1=Strongly Disagree

2=Disagree

3=Undecided

4=Agree

5=Strongly Agree

Helping friends and family is one of the great joys in life.

1=Strongly Disagree

2=Disagree

3=Undecided

4=Agree

5=Strongly Agree

I would avoid aiding someone in a medical emergency if I could.

1=Strongly Agree

2=Agree

3=Undecided

4=Disagree

5=Strongly Disagree

It feels wonderful to assist others in need.

1=Strongly Disagree

2=Disagree

3=Undecided

4=Agree

5=Strongly Agree

Volunteering to help someone is very rewarding.

1=Strongly Disagree

2=Disagree

3=Undecided

4=Agree

5=Strongly Agree

I dislike giving directions to strangers who are lost.

1=Strongly Agree

2=Agree

3=Undecided

4=Disagree

5=Strongly Disagree

Doing volunteer work makes me feel happy.

1=Strongly Disagree

2=Disagree

3=Undecided

4=Agree

5=Strongly Agree

I donate time or money to charities every month.

1=Strongly Disagree

2=Disagree

3=Undecided

4=Agree

5=Strongly Agree

Unless they are part of my family, helping the elderly isn’t my responsibility.

1=Strongly Agree

2=Agree

3=Undecided

4=Disagree

5=Strongly Disagree

Children should be taught about the importance of helping others.

1=Strongly Disagree

2=Disagree

3=Undecided

4=Agree

5=Strongly Agree

I plan to donate my organs when I die with the hope that they will help someone else live.

1=Strongly Disagree

2=Disagree

3=Undecided

4=Agree

5=Strongly Agree

I try to offer my help with any activities my community or school groups are carrying out.

1=Strongly Disagree

2=Disagree

3=Undecided

4=Agree

5=Strongly Agree

I feel at peace with myself when I have helped others.

1=Strongly Disagree

2=Disagree

3=Undecided

4=Agree

5=Strongly Agree

If the person in front of me in the check-out line at a store was a few cents short, I would pay the difference.

1=Strongly Disagree

2=Disagree

3=Undecided

4=Agree

5=Strongly Agree

I feel proud knowing my generosity has benefited a needy person.

1=Strongly Disagree

2=Disagree

3=Undecided

4=Agree

5=Strongly Agree

Helping people does more harm than good because they come to rely on others and not themselves.

1=Strongly Agree

2=Agree

3=Undecided

4=Disagree

5=Strongly Disagree

I rarely contribute money to a worthy cause.

1=Strongly Agree

2=Agree

3=Undecided

4=Disagree

5=Strongly Disagree

Giving aid to the poor is the right thing to do.

1=Strongly Disagree

2=Disagree

3=Undecided

4=Agree

5=Strongly Agree

NOTE: Scoring: Items 1, 5, 8, 11, 18, and 19 are reverse scored.

The scores for each item are summed up for an overall score from 20 to 100.

According to the author, a “Score of 60” is a neutral (or undecided) score.

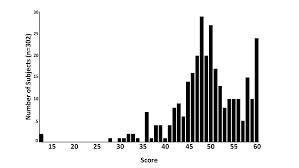

This instrument has been used in many research studies. I won’t belabor the data here, but a few summary findings are noteworthy.

Normative data on a sample of 302 adults.

A few key observations from research:

The mean HAS score is about 73.

Males score lower, at 72, than females, at 78.

Higher education is positively correlated with higher HAS scores.

Republicans score approximately 5 points lower than Democrats.

Affiliation with a religion or membership in a religious body results in a 5-point higher score than being unaffiliated.

After completing this instrument:

How do you feel about your personal views of helping?