Bipolar Disorder. How many times have you heard this term?

Do you have Bipolar Disorder?

How many people do you know who say they have Bipolar Disorder?

Since 2020, across epidemiological studies in the United States, bipolar disorder runs at 2.8% in the general population. This statistic represents 6 million persons.

The prevalence of Bipolar Disorder is similar for males (2.9%) and females (2.8%). Among young adults aged 18 to 29 years, the rate is about 4.7%. This particular statistic suggests Bipolar Disorder in adults will increase with time.

Bipolar disorder is a disability under the ADA, just like blindness or multiple sclerosis. If you have Bipolar Disorder, you may also qualify for Social Security benefits, especially if you can't work.

Bipolar disorder results in a 9.2-year reduction in life span. This is likely because as many as one in five persons with bipolar disorder completes suicide.

Discerning Bipolar Disorder

My specialty is complex diagnostics, so I’m interested in Bipolar Disorder because, as a diagnostic term, there are many different types, including Bipolar I and Bipolar II Disorder.

What are these differences?

How do they appear in the behavior of a diagnosed person?

It is useful to state what Bipolar Disorder is and is not.

The dictionary defines Bipolar Disorder as:

“an affective disorder characterized by periods of mania alternating with periods of depression, usually interspersed with relatively long intervals of normal mood.”

The key terms in this definition are Mania, Depression, and Normal Mood. The verb alternating is key, along with the word intervals.

The medical or psychiatric description of Bipolar Disorder is as follows:

An overarching term describing a group of affective disorders in which patients experience episodes of depression, identified by low mood, loss of pleasure and reduced energy, and episodes of either elated or irritable mood or both, and related symptoms such as increased energy and reduced need for sleep. These two opposite states alternate in a discernable pattern. It is distinguished from unipolar depression, which is still a cycling disorder, but the cycle never crosses the line into mania or hypomania.

Within this overarching definition, there are multiple sub-states identified by more specified terms:

Bipolar disorder type I

Bipolar disorder type II

Cyclothymic disorder

Bipolar disorder not otherwise specified

Bipolar Disorder type I

Episodes of depression and at least one episode of full-blown mania

Bipolar Disorder type II

Several protracted episodes of depression and at least one hypomanic episode but no manic episodes

Cyclothymic Disorder

Many periods of hypomanic and depressive symptoms in which the depressive symptoms do not meet the criteria (of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) for a Unipolar Depressive disorder.

Bipolar Disorder not otherwise specified

Depressive and hypomanic-like symptoms and episodes that might alternate rapidly, but do not meet the full diagnostic criteria for any of the aforementioned Bipolar Disorders or Unipolar Depressive Disorder.

Below is a chart depicting the cycling of these disorders. The top letter on the far left M=Mania or m=hypomania. The bottom letter D=depression.

The medical definition provides a lot of detail, and the flow of the medical terminology is straightforward and not too different from the core dictionary definition: Mania, Depression, Normal Mood that alternates at specific intervals.

Understanding the term Bipolar Disorder makes several assumptions of the reader. First, that you understand what a depressive disorder is, and Second, that you know what mania is and what distinguishes between mania and hypomania.

Given the broad strokes that the overview medical definition of Bipolar Disorder covers, it is not surprising that large numbers of people are diagnosed with the disorder.

Still, it is perplexing that this broad definition is then followed, in the field of pharmacology, with pinpoint drugs developed to treat it. This is probably one reason that people diagnosed under these labels get prescribed all kinds and classes of drugs. Because the disorders themselves are elusive, practitioners are generally left with trying to find good treatment approaches without much direction or guidance (from the diagnostic labels) or predictable symptom complexes. Given this, it’s not surprising that many people with Bipolar Disorder don’t feel confident that current treatment approaches are helpful.

Do I have Bipolar Disorder?

This is a question many people ask.

Once again, the answer boils down to identifying the disorder and its subtypes. This is generally done through client self-report and rating scales. Self-report scales come in the form of checklists, tests, and interview schedules created over time to capture the 1. behavior, 2. thinking, and 3. feeling states of persons suffering from Bipolar Disorder. Below is one example of a common test designed to identify Bipolar Disorder.

MOOD DISORDER QUESTIONNAIRE

Instructions: Check ( ✓) the answer that best applies to you.

1. Has there ever been a period when you were not your usual self and: (check all that apply)

…you felt so good or so hyper that other people thought you were not your normal self or you were so hyper that you got into trouble?

…you were so irritable that you shouted at people or started fights or arguments?

…you felt much more self-confident than usual?

…you got much less sleep than usual and found you didn’t really miss it?

…you were much more talkative or spoke faster than usual?

…thoughts raced through your head or you couldn’t slow your mind down?

…you were so easily distracted by things around you that you had trouble concentrating or staying on track?

…you had much more energy than usual?

…you were much more active or did many more things than usual?

…you were much more social or outgoing than usual, for example, you telephoned friends in the middle of the night?

…you were much more interested in sex than usual?

…you did things that were unusual for you or that other people might have thought were excessive, foolish, or risky?

…spending money got you or your family in trouble?

2. If you checked YES to more than one of the above, have several of these ever happened during the same period of time? __Yes__No

Please check ONE response only.

3. How much of a problem did any of these cause you

like being able to work; having family, money, or legal troubles; getting into arguments or fights? __alot__some__a little__none

Please check ONE response only. —-No problem, —-Minor problem, —-Moderate problem, —-Serious problem

4. Have any of your blood relatives (ie, children, siblings, parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles) had manic-depressive illness or bipolar disorder? __Yes__No

5. Has a health professional ever told you that you have manic-depressive illness or bipolar disorder?__Yes__No

If you answer 7 or more of the events from question #1 and you report YES to question #2, and you answer (Alot or Some) to question #3 then you would likely be diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder. Questions #4 and #5 are not essential for scoring purposes.

As you read through this questionnaire you will notice a pattern. The questions focus mostly on mania. For this reason, this instrument is always given with a second instrument designed to assess for depressive symptoms.

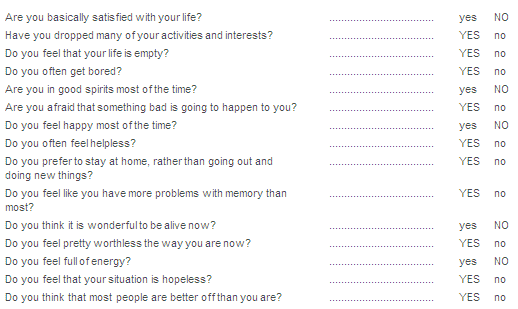

Geriatric Depression Scale (short form)

The Geriatric Depression Scale (short form) is a quick assessment of depressive affect and it is what a clinician might administer to evaluate if a person is also experiencing depression. If you read through these questions you will notice that questions evaluate your: 1. thinking, 2. feeling, and 3. behavior.

Disorders that Mimic Bipolar Disorder

Because the features of Bipolar Disorder are general, it can get confused with other conditions, such as “Personality Disorders.” A common discernment issue is between a. Bipolar Disorder and b. Borderline Personality Disorder.

Below is a chart that tries to disentangle a person’s behavior by highlighting issues that may appear like Bipolar Disorder, but the person is experiencing a Personality Disorder. NOTE: A personality disorder relates more to a person’s overall character (moral judgment) than to how a person is experiencing emotions at any specific time (Sustained Mood Shifts).

What is it like to have Bipolar Disorder

The experience of Bipolar Disorder in whatever form is difficult, unpleasant, painful, trying, and at high levels of severity can be a lethally dangerous condition. Not only is the person with Bipolar Disorder in substantial personal pain and discomfort, but others in the person’s world (spouse, children, parents, friends, relatives, co-workers) also experience great stress.

Margaret and Bipolar Disorder

Margaret saw me for several years due to difficulties she experienced coping with Bipolar Disorder. She remarked that when she had Bipolar symptoms, she felt as if she was trapped in a glass bottle. A Bipolar Disorder medicine bottle, of which she couldn’t get out. She had been hospitalized twice for severe immobilizing symptoms so far during her lifetime. She was currently taking multiple medications, one of which was lamotrigine (an anticonvulsant drug that has been shown to prevent, at times, extreme mood swings). Her disorder had strained her marriage and her relationship with her parents and her in-laws. She had contemplated suicide but had never acted on these thoughts.

During her “low” or depressed (D) phase, she was nearly immobilized, stayed in bed most days, and got up only for essential tasks such as using the bathroom and toweling herself once a week (she stopped taking showers or baths). She said during these times that her bedroom felt like her prison, “my room was stale, my body was wasting away, I looked and smelled awful, and there was absolutely nothing I could do about it.” As the state continued into a month, Margaret would languish. People stayed away from her. She said, “My husband brought food to my bedroom when I could eat, would lay it on the bed, and leave; we never talked or discussed things; he is patient and kind, and I knew he was just waiting it out. He was trying to avoid my rollercoaster mood affecting him.”

Then, for reasons unknown, she would start snapping out of it. Her energy would return, her mood would lift, her outlook would improve, and then there would be a short period of what she called “normalcy.” This, she said, “ life became OK, at least worth living, and that’s why I endured the hardships - hoping for this to come around.”

She’d seen so many psychotherapists over the years that she’d lost count. When she got depressed, she said that most of these paid helpers would just fade away. It is more likely that she would start missing appointments, bills got missed, or when she saw someone during this time, she would provide almost no input during the sessions, just end the sessions of her own volition. She said, “The therapist would be reduced to talking to the wall.”

She’d tried, during these periods, alternative intervention strategies, ECT, TMS, massage (when she could get, fight with the insurance companies and expend the energy to get one of these procedures started - for her, they were never worth the effort and cost).

Following the period of normalcy, Margaret would start getting what she called, “edgy.” By this, she meant, she would become irritable, harsh towards others, impatient, would want to go places (it didn’t matter where) and do things, and wouldn’t be content while doing something. She reported once sitting in a movie theater with her family, then all of a sudden, she hated the movie, and she got up, left, went to the lobby, and then started bingeing on snacks, popcorn, candy, and soda until she felt bloated and physically ill. Her kids got tired of trying to figure out what she was doing, so they just let her engage in these acts while they watched the movie. But, she did enjoy the movie theatre waiting room because she would watch people entering other shows. The movie crowds excited her more than the boring show (It didn’t matter what the show was about).

She reported once going with her mother (who was also diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder) to Las Vegas for a “girls” weekend. While there, she made a pass at a younger male gambler, there was a brief one-night stand, and then she felt guilty, saying, “This should never have happened, it was totally out of character for me, it was degrading, and my mother just disappeared and, by doing so, almost condoned the action.” This event nearly broke up her marriage.

Margaret’s diagnosis was tricky because some of her behaviors fit into another diagnostic scheme (Borderline Personality Disorder), except that this kind of behavior never happened when she was depressed, she did have several life-long friends, and she didn’t show signs of this as a child. Margaret’s childhood was, for the most part, good, at least as she reported it to me. There was no history of borderline behaviors in her family of origin, and no abuse of any kind that I could detect. When she was in a normalcy phase, the parenting of her children was good to excellent.

Did Margaret have a “strong” case for Bipolar Disorder?

It’s hard to know, but this was the working diagnosis.

How does one intervene with someone like Margaret?

What is the likelihood that she could develop coping strategies to deal with her condition?

What role does psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy play in her situation?

When I began working with Margaret (which was a while back), the first phase of our treatment program was to have her begin tracking her mood. Curiously, even though she had seen multiple psychotherapists, they frequently operated from a lack of knowledge about the longer-term patterns of her mood, say, over a year’s time frame.

To her credit, Margaret was committed to tracking her moods. It took work, but we finally devised a tracking strategy for her. This involved a paper-and-pencil approach, but more recently migrated to using a web application entitled “moodnotes (https://apps.apple.com/us/app/moodnotes-mood-tracker/id1019230398)

I’m not necessarily a fan of “moodnotes” for tracking, and there are other options (some entirely free), but this one appealed to Margaret. She liked the faces (that mark mood states), the word descriptors, and the open-ended response format. This latter feature was helpful because in mood notes, she and I also had quantified rating questions (in the paper-and-pencil tracking scheme) that we built in to help track specific behaviors and feeling states that we conjectured would be active in assessing Margaret’s change from one state to the next.

We did all this work while Margaret was in a “normalcy” phase. Then, it was tracking, meeting, waiting, discussing, refining the tracking strategy, tracking, waiting, discussing, and so forth (first twice weekly, then weekly). It’s a bit surreal doing this because we were anticipating that in a short time, she would shift into another big depressive or manic mood state. I wondered if she could keep tracking these states.

Either way, we would pin down the pattern, over a year, of her moods (when they would start, how long they would last, severity, patterns of change). Curiously, once the tracking was in place for the first year, nothing happened. What I mean here is that she had no shift in her moods; she went for a full year of normalcy (tracking, waiting, discussing, tracking, waiting, discussing, and so forth). Perhaps something did happen, but it is hard to figure out if this part of her cycle (which is a gigantic pattern of mood swings) or if something about tracking her moods had the effect of disrupting some kind of biological process (which I was conjecturing) was driving these shifting mood states.

Maybe, from Margaret’s point of view, a better way to put it, is that something did happen. She finally said, “Doc, you cured me!” When, in actuality, I did nothing more than set up a tracking system and meet with her weekly to discuss her issues, as in typical therapy, and discuss her tracking, which she did with great energy and precision. She never missed a day, she was focused on it, almost like it was a sign that she was improving.

It is possible that what Margaret needed was, perhaps, 1) a psychotherapist who would stick with her and to whom she could relate and 2) a good tracking system that is vigorously discussed each week without fail.

But even though Margaret was satisfied with her life going well and having mostly positive experiences, her world was starting to trust her stability and relate to her differently, and she was now being reinforced by the world again for being non-depressed. This is a VERY IMPORTANT point. Sometimes, the environment (family, friends, community) characterizes a person with bipolar disorder and might start inadvertently reinforcing the condition. If the person changes, the environment might resist that change, sometimes for very understandable reasons pushing the person back into the pathological role.

I wasn’t confident that the Bipolar condition was gone forever, although it was possible. She was still taking her medication. I thought, “It can’t be that simple or easy…” But, then again, the individual human psyche, including mine, has baffled me. Plus, if this was the case, it might be that the condition is still present, but between the medications/tracking/Margaret’s changed POV, this could be pushing the state into a sub-clinical level (still there but being mediated, autonomically, by Margaret, herself.

The fact is, eventually, things did change for Margaret, however. Perhaps, as a reader, you are becoming aware that this is a much longer story, so I will return to Margaret later…